It was the best of times. It was the worst of times. It was the century, as the historian Kevin Sharpe wrote, summing up the Whig view, ‘in which the champions of law and liberty, property and Protestantism triumphed over absolute monarchy and popery and laid the foundations for parliamentary government’. It was a century of recurring plagues and fire and bloody civil war. It saw successive waves of witch hunts, the beginnings of the Enlightenment and the founding of the Royal Society. It saw revolution and regicide followed by restoration and revolution again. In its first years, Shakespeare, Webster and Donne were working, contemplating mortality and anatomising passion in the same gorgeous language that gave us the King James Bible, the most ambitious and successful state-funded literary project this nation has ever seen. In its latter half, the literary stars were satirists or foppish comedy writers and the intellectual titans were mathematicians and scientists – Hooke, Harvey, Newton, Wren and Boyle.

People thought the unthinkable –universal male suffrage, legal aid, even a national health service

It is no wonder that historians have repeatedly been drawn to the British 17th century. Two years ago Clare Jackson gave us, in Devil Land, a vision of Stuart Britain that situated it in its international context. James I, ending the isolationism of Tudor England, sent his diplomats as far afield as Moscow, Constantinople, even Mughal India, and welcomed foreign ambassadors to his court. Jackson drew on their reports, and on those of subsequent travellers, including the royalist exiles of the mid-century, to show us a nation whose repeated upheavals mirrored, and intersected with, those of mainland Europe. Now comes Jonathan Healey, telling a parallel story in a very different book. Where Jackson was cosmopolitan and favoured the overview, Healey’s tendency is to keep low (socially), stay local and dig deep.

Healey’s prose is precise but colloquial. He presents complex arguments, but delivers them in a laid back, often jocular manner. The style matches his inclusive choice of subject matter. He is interested in preachers and vagabonds and the apprentices who riot in the streets, as well as in MPs and peers. Inevitably, he draws on parliamentary debates and the correspondence of grandees, but many of his most vivid passages are based on the proceedings of the minor magistrates’ courts where petty cases were examined.

He tackles big subjects – religious dissent, the legal system – but hitches them to piquant stories about individuals previously unknown to history. A chapter on shades of religious belief, and their overlap with political divisions, begins with an account of a raucous prank in a church in rural Yorkshire, involving the invasion of Sunday matins by a noisy procession of locals beating drums and blowing bagpipes, and the mock marriage of a couple of young men. A chapter full of data about population growth is framed by the story of a radical leader, one of the first of the Levellers, named Captain Pouch after the mysteriously significant satchel he carried, which was found, after his execution, to contain nothing but a piece of green cheese.

A conversation in a Somerset alehouse between the publican and two farmers, which results in one of the latter being arrested for seditious talk, leads in to a chapter on the burgeoning of news gathering and news transmission – a novel phenomenon that Healey rightly identifies as being politically transformational. In London, the Royal Exchange (a shopping mall-cum-stock exchange) and St Paul’s cathedral were the two great information hubs. From them, wrote a visitor, rose a noise, ‘like that of bees, a strange humming or buzz’. There gathered sea captains home from foreign parts, lawyers, money lenders and courtiers, all swapping information, while what they said was snatched up by the writers of newsletters.

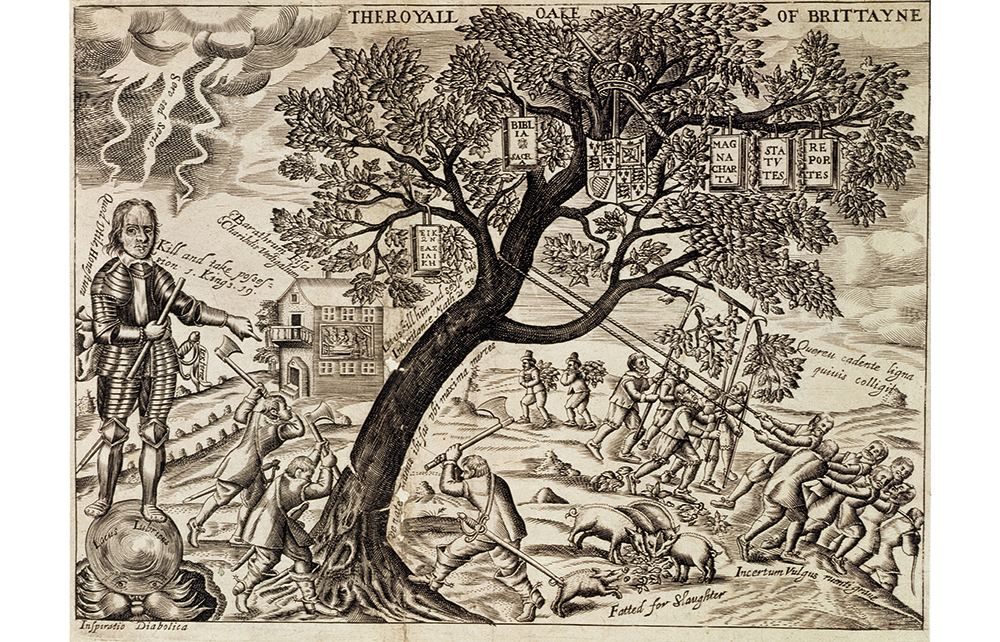

Landowning gentlemen in the shires, merchants and diplomats abroad, all had their news hounds in town. Pamphlets and corantoes (news magazines) and libels (scurrilous gossip often in verse) were for the literate and increasingly vocal ‘middling sort’. For non-readers there were sermons. Popular preachers might address congregations of thousands. Through all these channels passed information and opinion, little of it totally trustworthy, some of it inflammatory. A French visitor was disturbed. He wrote: ‘Audacious language, offensive pictures, calumnious pamphlets, these usual fore-runners of civil war are common here.’

He was right, of course. The civil war began in Scotland. Healey, typically looking at its consequences for the ordinary citizen, opens a chapter with news about rising energy costs. For Charles I the conflict with the Covenanters was about the limits of royal authority: for his subjects its importance lay in the fact that the price of coal from Scottish-occupied Newcastle was shooting up. Healey segues into the unhappy experiences of a cleric with the unfortunate name of Dr Duck, who was pursued by a mob throwing stones and making quacking noises, a crude bit of humour that leads on into one of Healey’s dominant themes: the growing importance of popular demonstrations. As the institutions of church and state began to quake, faith and politics moved out of doors. Religious observance shifted from the churches to illicit meetings ‘on hills and heaths, in suburban lanes, or by owl-light’, and parliamentary debate was punctuated by the yelling of the crowds outside the windows of the Palace of Westminster.

The ruling class were bewildered. In December 1641 MPs were debating the wording of the Grand Remonstrance. ‘I did not dream,’ said one of its opponents ‘that ever we should remonstrate downwards, telling stories to the people.’ Equality was a terrifying thing. Royalists feared that ‘the common people’ would ‘destroy all distinctions of families and merit’ and usher in a ‘dark equal chaos of confusion’. But apprentices and ‘other inferior persons’ were marching. People power was growing. Healey zestfully records its crescendo.

His focus on ‘common people’ does not mean he is unduly partisan. He is fair to generous in his assessment of Charles I’s late-developing political skills. He sets up no idols. He considers it a pity that Oliver Cromwell ended up dominating the republic: John Lambert, the chief author of the Protectorate’s Instrument of Government would have been his choice – ‘a finer general and certainly the greater intellect’.

His storytelling lights up most vividly when he is writing about radicals and visionaries – the Agitators, Quakers, Muggletonians, Ranters and Fifth Monarchists. ‘The revolution brought an extraordinary moment of ideological creativity.’ People thought the unthinkable – universal male suffrage, legal aid, a national health service. ‘The Old World,’ wrote Gerrard Winstanley, the leader of the Diggers, ‘is running up like parchment in the fire.’ Healey blows on the flames. He writes eloquently about the fiercely righteous John Lilburne; he celebrates those who would turn political systems upside down; but he also honours technicians and agricultural innovators and educational reformers. Events were tumultuous, but Healey persuasively shows us that thoughts were as thrilling and sometimes as wild.

Cromwell died, and General Monck, the unlikely king-maker – whom Healy deftly brings alive in one of numerous vivid thumbnail sketches in this book – made his move. The Stuart monarchy was restored. Charles II’s reign was nothing like as merry as royalist romancers would have had us believe, with plague, fire, plots and hangings. And then came the hapless James II and his deposition/abdication. After all the turmoil and hope and slaughter of the mid-century, the latter part of the Stuart period is anti-climactic, petering out into the disturbingly ambiguous development known to posterity as the Glorious Revolution which – viewed another way – looks awfully like a successful foreign invasion. Healey does his best to keep up the momentum, bringing John Locke to the fore, but his narrative has a dying fall.

Compendious and lucid, The Blazing World is an engaging addition to the historical literature on the period. Under the divided revolutionary government, as the New Model Army and parliament disputed power, unheard of freedoms sprouted. The shocked Countess of Derby noted that ‘the Quran is printed with permission’, and that everyone was being allowed to preach – ‘even women!’ Healey celebrates the heady intellectual ferment with proper seriousness but – keeping his eye on low pleasures as well as high-mindedness – records that a popular manual on dance steps included the cheerily boisterous sounding ‘Up Tails All’, the ‘Punks’ Delight’ and the ‘Rufty Tufty’. His book will mostly be read by students, as such books are: their essays will be the livelier for it.

Comments