‘Fine old Christmas,’ wrote George Eliot, ‘with the snowy hair and ruddy face, had done his duty that year in the noblest fashion, and had set off his rich gifts of warmth and colour with all the heightening contrast of frost and snow.’

Thus opens the second chapter of Book II of The Mill on the Floss. I had found the passage when searching for a secular reading for my newspaper column’s readers at a carol service at St Bride’s church in Fleet Street a couple of nights ago. I knew at once I’d found what I wanted.

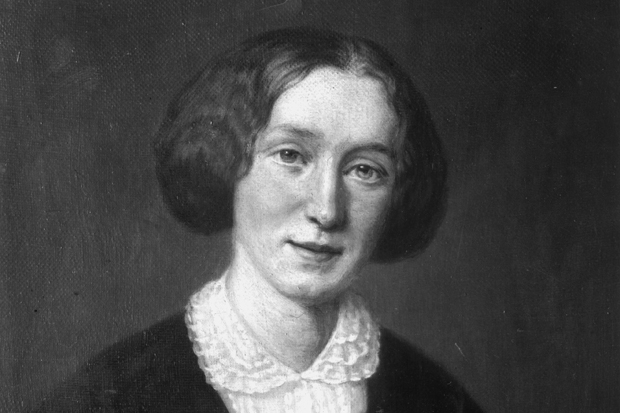

Eliot had been my first port of call. You can be confident she will avoid religiosity yet never take refuge in mere jollity. She is never pat. Not for her the ‘Deck the hall with boughs of holly, fa-la-la-la-la la-la-la-la’ piped merriment, content-light and designed to infuse supermarket shoppers of all faiths and none with a desire for more chocolate. Not for her the secular festivity calculated to put the X into Xmas. I knew she’d shy from that. I read on…

Snow lay on the croft and riverbank in undulations softer than the limbs of infancy … there was no gleam, no shadow, for the heavens, too, were one still, pale cloud; no sound or motion in anything but the dark river that flowed and moaned like an unresting sorrow.

As ever, Eliot’s descriptive flight of the imagination has an intelligent purpose which soon becomes clear. ‘But old Christmas smiled as he laid this cruel-seeming spell on the outdoor world,’ she writes, ‘for he meant to light up home with new brightness, to deepen all the richness of indoor colour… he meant to prepare a sweet imprisonment that would strengthen the primitive fellowship of kindred, and make the sunshine of familiar human faces as welcome as the hidden day-star.’

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in