Donald Winnicott once told a colleague that Tolstoy had been perversely wrong to write that happy families were all alike while every unhappy family was unhappy in its own way. It is illness, Winnicott said, that could be dull and repetitive, while in health there is infinite variety.

Winnicott was reared in an environment of plain-speaking west-country Methodism. He was a people’s doctor who earned his spurs in the crowded children’s wards of east London’s wartime hospitals, allergic to dogma and fearless of being labelled a heretic. He believed that mothers did not need experts to tell them how to care for their own babies and, equally, that artists didn’t need to be justified or understood by psychoanalysts.

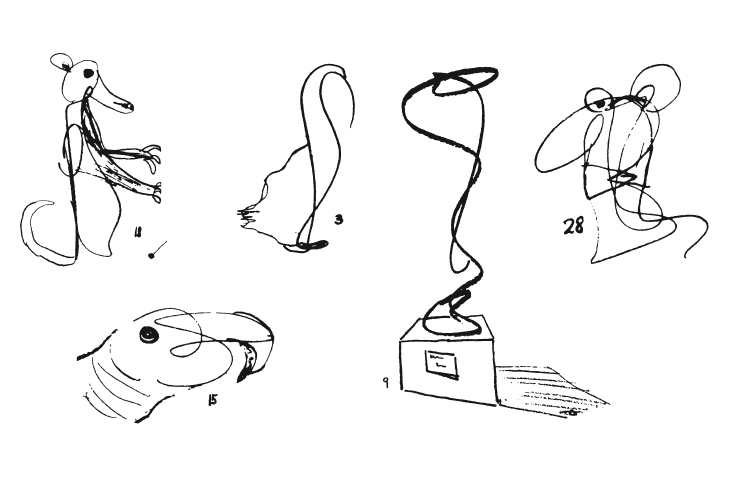

Yet Winnicott — the great psychoanalyst — made creativity, spontaneity and playfulness the sine qua non of his life and work. He and his wife Claire, an influential child social worker and analyst in her own right, would hand draw or paint their own Christmas cards each year to send to their friends. He filled his letters with witticisms and drawings, and regularly doodled, rather than wrote, his signature. Some examples of this can be seen for the first time in OUP’s new Collected Works of D.W. Winnicott.

Winnicott’s writings on the place of creativity in health and illness were subtle and balanced; he was not interested in using psychology to analyse an artwork as if it could be read as a symptom.

To think about the phenomenon of creativity, of being able to create something out of our imagination, Winnicott takes us right back to the beginning to examine our very first phase of life. The newborn baby has no conception of the outside world; he is not a philosopher with theories about what the world is or whether it exists.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in