The 1960s were swinging. The 1970s were stagflationary. In the 1980s we made loadsamoney and greed was good. The 1990s were dot.commy. And the 2000s were the boom and bust decade.

Characterising ten-year periods in this casual way is something journalists love to do. It’s deplorably unscientific and yet pleasingly decentralised. A consensus simply emerged that the 1960s were swinging, even if the overwhelming majority of human beings did not turn on, tune in and drop out. The overall quantities of love and war were roughly the same as in the 1950s.

Historians shouldn’t object. Such epithets give us something to argue against. (‘Far from being “swinging”, for most people the 1960s were indistinguishable from the previous decade…’ and so on.) But before the revisionism can begin, we need the consensus. So how is the past decade going to be remembered? As the Trumpy 2010s? And what will this new one be like? The Thunbergian 2020s, perhaps? Or maybe just — if Greta turns out to be right and Australia barbecues itself to ash, Venice joins Atlantis beneath the waves, and Asia asphyxiates — the Last Decade?

For future historians of British politics, the 2010s may be depicted as a rather old-fashioned tale of two Etonians: one suave, smartly turned-out and always well prepared; the other rambunctious, dishevelled and often obviously winging it.

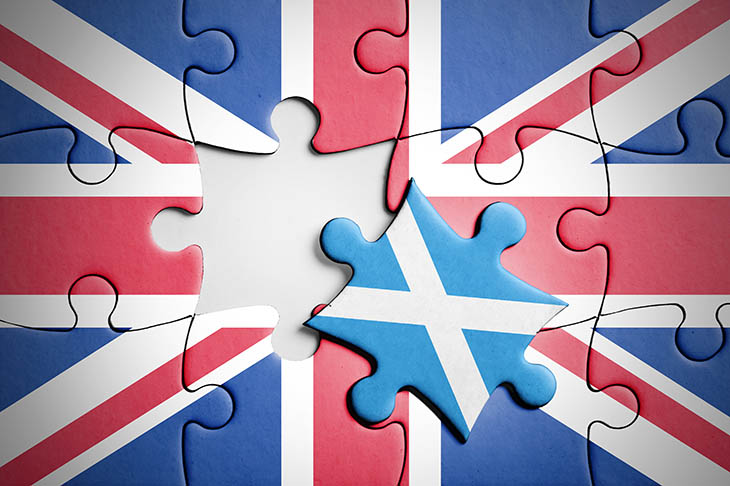

David Cameron won enough votes and seats in the election of May 2010 to oust Gordon Brown from 10 Downing Street, ending the New Labour era by forming a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. Cameron saw off the proponents of Scottish independence in September 2014 and won an outright Tory majority in May 2015. Yet power slipped from his grasp because his nemesis Boris Johnson backed Brexit in the following year’s referendum on European Union membership.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in