They already had four children, four cats, four dogs, a number of horses and a pet pig called Philip. But for Alan and Judith Kilshaw, this wasn’t enough. When IVF failed, they decided to try to adopt another child. What happened next would lead to them being pursued by the FBI, as well as a media frenzy, a fraught transcontinental legal dispute and international notoriety.

In the spring of 2000, they were simply an eccentric couple living in obscurity in a ramshackle farmhouse with their children and menagerie in the small town of Buckley, north Wales. Unable to conceive again, even with medical assistance, the Kilshaws began looking into the possibility of adoption – only to discover that they were unlikely ever to meet with any success in the UK. And this led them to explore the then briefly booming area of adopting overseas.

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, a 28-year-old woman in St Louis, Missouri, was heavily pregnant – very heavily pregnant. Tranda Wecker would soon discover she was carrying twins. And being single, in social housing and just about holding down a low-paid position at Wal-Mart, this wasn’t welcome news.

Wecker found an online adoption broker, the ‘Caring Heart Agency’, who arranged a deal with a couple from California, Vickie and Richard Allen, who would pay Wecker $6,000 to take the two babies. Wecker gave birth in June 2000 to two girls she named Kiara and Keyara, and they were soon delivered to their new home out west.

But just as the deal went through, Caring Heart began to get messages from the UK, from a couple called Kilshaw, who were apparently more excited by the prospect of twins than any single-child alternatives. Undeterred by the news that Kiara and Keyara had already been homed, the Kilshaws pushed Caring Heart and Wecker to allow them to gazump the Californians by doubling their fee.

The Allens were lured into meeting Wecker in the lobby of a hotel in San Diego after she pleaded that she was desperate to see her daughters one final time. But instead of saying an emotional goodbye, Wecker grabbed the girls – there was even reportedly a scuffle as she tried to escape – and handed them to Alan and Judith Kilshaw, who gave her $12,000 in return, then raced to their waiting car.

The furious Allens alerted the police and then the FBI, who tried to catch up with the Kilshaws, Kiara and Keyara, as they made a desperate 2,000-mile road trip. Incredibly, they managed this, eluding capture, completing a pseudo-legal adoption and flying out with the girls to Manchester and on to the family home in Wales before the US authorities could stop them.

I first heard of the Kilshaws at about 4.45 a.m. on Tuesday 16 January 2001 – just a few hours before the rest of the UK woke up to find out about them and their strange adoption. In an attempt to recoup some of their understandably hefty ‘adoption’ expenses, the couple had sold their story to the Sun, who had given it ‘World Exclusive’ treatment across seven pages.

It seems impossibly quaint now, but in those days the idea of carrying out any kind of transaction online was a relative novelty, so the twins – by now renamed Kimberly and Belinda – were described in that initial story, and became known in the media generally, as ‘the internet babies’.

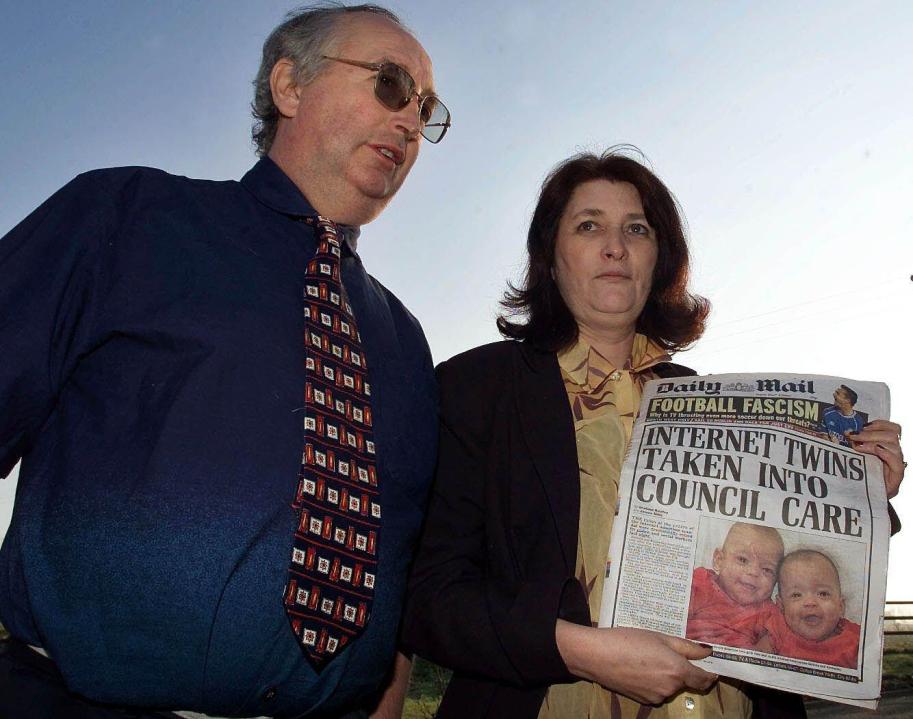

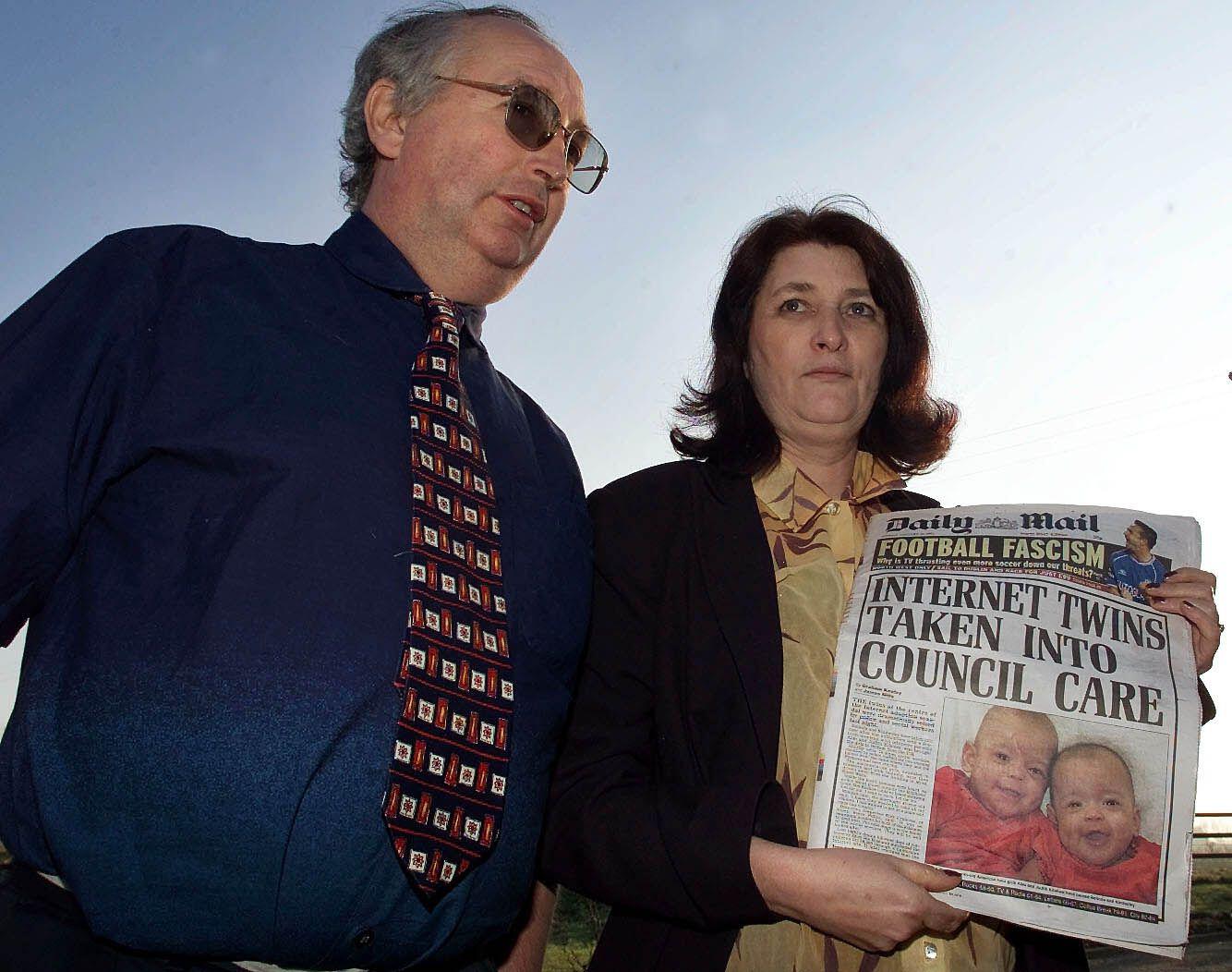

I was a reporter on the Evening Standard and got that very early call explaining this saga in a couple of lines and telling me to race to north Wales to find out more. So by 11 a.m. I found myself with several dozen other hacks and photographers in an improvised conference room in a small provincial hotel, the Beaufort Park, near Mold, to meet the Kilshaws – as a later documentary would be titled.

In an attempt to recoup some of their understandably hefty ‘adoption’ expenses, the couple had sold their story to the Sun

The couple were still under contract to the Sun and the purpose of the event was to stoke wider interest in the paper’s story. Alan and Judith would read a prepared statement and briefly pose for pictures before being whisked away. They wouldn’t be taking questions.

Or at least, that was the plan. But things began to unravel almost as soon as the couple were led out. It was immediately obvious that the Kilshaws were everything you wouldn’t look for in the subjects of an expensive newspaper buy-up. Nor, indeed, in prospective parents. They certainly weren’t going to allow their freedom of expression to be curtailed by any mere exclusive contract.

I still remember the spectacle of flustered Sun reporter Charlie Yates trying and failing to shut them up as the press conference turned to chaos. But as soon as he’d corralled Alan away from the Telegraph, the Mail and Sky News, he would look up to see Judith spilling her innermost thoughts to the Mirror, the Express, ITN and me. It was a shambles.

All this went out on the early evening news and in the next day’s papers and the legend of the Kilshaws was born. Their story went global. They even appeared on Oprah. In the frenzy that followed we learned more about their eccentricities: Judith was a self-proclaimed witch who used voodoo dolls; they believed their house was haunted; they threw ‘vicars and tarts’ parties; Philip the pig was a regular visitor to their kitchen. Prime Minister Tony Blair described the affair as ‘disgusting’. Judith was labelled ‘the most hated woman in Britain’.

And things very quickly began to go wrong for the Kilshaws. Flintshire social services soon saw enough and removed the girls under an emergency protection order, handing them to vetted alternative foster parents. The original US adoption was annulled.

Then there was that custody battle at the High Court. It did not go their way. The judge, Mr Justice Kirkwood, condemned the Kilshaws as ‘media-obsessed’ with no genuine concern for the welfare of the twins. The girls were returned to the US and yet another set of foster parents. The law was changed to stop cowboy overseas adoptions happening again. Judith has always insisted that what she and Alan did was entirely legal and that they were victims of a media witch hunt.

Despite the various media appearance fees, the whole affair left them £50,000 in debt. Alan lost his business and never worked again. The Buckley farmhouse was repossessed. The Kilshaws split up. Judith married a man 13 years her junior whom she had met in a nightclub. And barely into his sixties, Alan died of a lung condition in 2018. Judith is still with us, somewhere, last heard of working as a part-time cleaner.

Now living back under their birth names, Kiara and Keyara refuse to see Wecker – but she reportedly gatecrashed their graduation ceremony six years ago, the last update we had. And the story is periodically retold on screen, most recently in a 2022 BBC documentary series, Three Mothers, Two Babies and a Scandal. But my memory of the Kilshaw scandal always reverts to that first day.

At the height of the chaos of the press conference, the babies themselves were not only brought out but, incredibly, were actually passed around the room. Somehow, I ended up holding both girls at once. And I looked up to see the entire press pack following these two nutjobs out of the French doors into the hotel grounds for pictures, apparently forgetting their ‘daughters’.

So I was briefly alone with these suddenly famous babies, one in each arm. I remember thinking how easy it would be to simply take them out to my car and drive off with them, back to London. And from what I’d seen of their adoptive parents, it felt almost that this would be the right thing to do.

Comments