Joseph Conrad’s death made Graham Greene feel, at 19, sitting on a beach in Yorkshire, ‘as if there was a kind of “blank” in the whole of contemporary literature’. Greene’s own death in 1991, aged 87, had a similar effect on many younger writers, myself included.

For John le Carré, his most obvious successor, Greene had ‘carried the torch of English literature, almost alone’. His cool fugitive presence, in Martin Amis’s phrase, had been there all our reading lives. In an age of diminishing faith, he had used Catholic parables in a way that lent them a power beyond their biblical origins, mining the gospels rather as le Carré has mined the Cold War. Shaking his hand in Moscow in 1987, Mikhail Gorbachev spoke for an international audience: ‘I have known you for some years, Mr Greene’ — although it was unclear whether as an admirer of his novels, or if Russia’s president had seen his name in intelligence reports concerning Latin America.

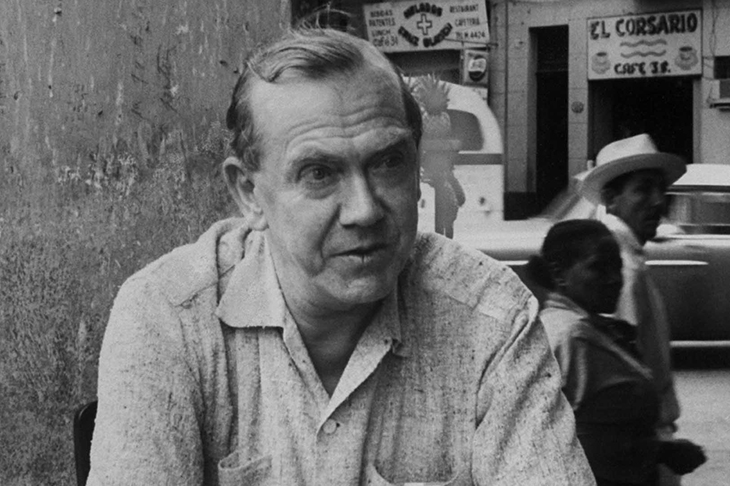

About Greene’s character, less consensus reigns. Congenitally elusive, he refused to appear on television. ‘I feel I’ve got a copyright on my life,’ he explained to me, ‘and that people I know should have a copyright on theirs.’ How much of his secretiveness was vanity is hard to tell.

Unable to pronounce the letter ‘r’, his instinct was for self-effacement — ‘I am so shy’ were his first words to Kim Philby’s Russian wife. Yet co-habiting the same skin — ‘faintly sunburned, with the texture of fine dry silk’, recalled one mistress, Jocelyn Rickards — there writhed a provocative exhibitionist whose love-making with Rickards as they travelled first-class by train to Southend was conducted in blatant view of those on the platforms.

Definitely, there were aspects of his life that he hated, even if others thought it a good thing to be him, and pinched his identity.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in