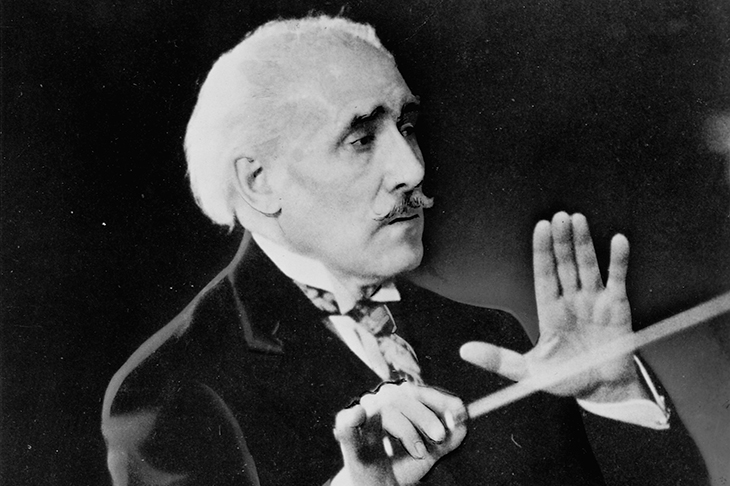

Now he is the greatest figure for me, in the world. [Toscanini is] the last proud, noble, unbending representative (with Salvemini) of the Risorgimento & 19th-century ideals of human liberty… not just a great conductor but a symbol of discipline and spontaneity in one — the most morally dignified & inspiring hero of our time — more than Einstein, (to me) more than even the superhuman Winston [Churchill].

That is Isaiah Berlin writing in 1952, two years before his hero’s last concert, and as quoted by Harvey Sachs in this magnificent biography.

Though Berlin’s encomium is extreme, it isn’t unrepresentative of the kind of things that were being written about Arturo Toscanini for many years before his death in 1957. Somehow — and it is the arduous task of the biographer to work out how — his widely recognised greatness as a conductor was bound up with his stand against fascism, his refusal to conduct in countries where fascist dictators ruled, and his nourishingly simple set of values, which made him certain of the rights and wrongs of everything to which he gave his attention.

Get Britain's best politics newsletters

Register to get The Spectator's insight and opinion straight to your inbox. You can then read two free articles each week.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in