In the 1850s Britain was hit by an epidemic likened by The Illustrated London News to a ‘grippe or the cholera morbus’. It came from America rather than China and afflicted the mind rather than the body. The craze for table-turning was sparked in Hydesville, New York, in 1848 after two young sisters, Maggie and Kate Fox, claimed to hear mysterious rappings in the floor of the family home and attributed them to a spirit called Mr Splitfoot.

Epidemics are by nature democratic, respecting neither education nor class. Eminent naturalists, scientists, novelists and social reformers were gripped by the grippe. When unseen forces such as electromagnetic waves were being discovered, who was to say they might not include channels for communication with the dead? In an age when few families, rich or poor, were untouched by premature bereavement there was a predisposition to belief. Spiritualism assumed the status of a religion presided over by a new class of mediums, mainly women, who seemed the natural conduits for spirit guides.

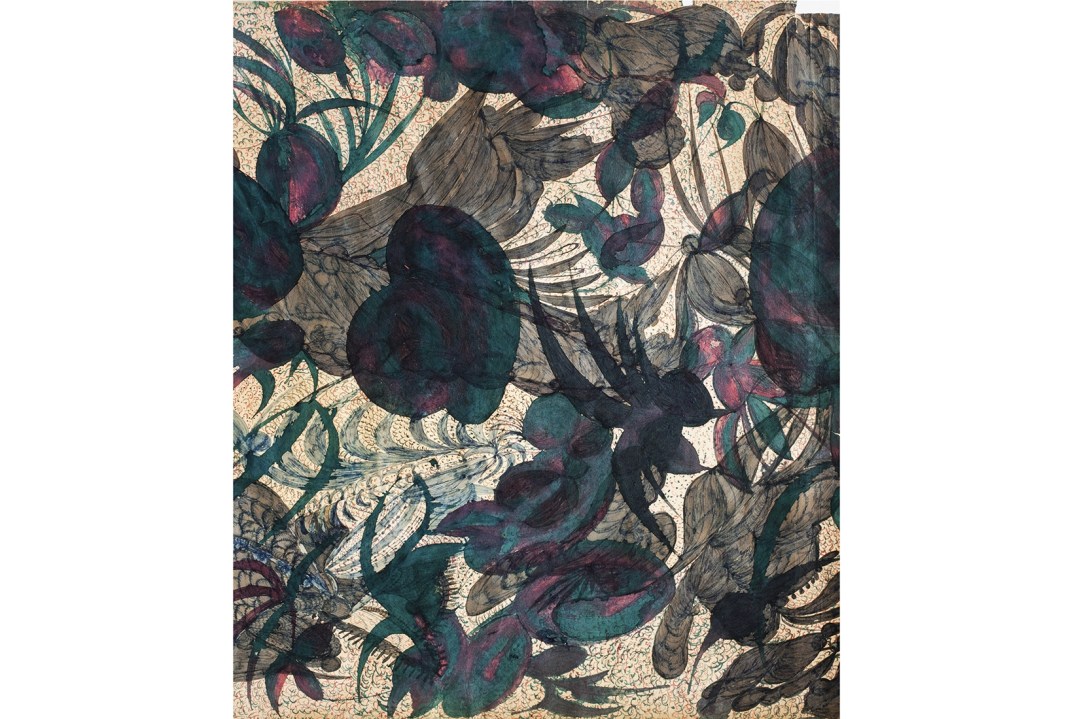

A show of the mediumistic painter Hilma af Klint broke all attendance records at the Guggenheim

The fad might have left no physical trace had it not gelled with another Victorian female pastime: watercolouring. In 1856 Anna Mary Howitt, who had studied at Sass’s Academy with Holman Hunt and Rossetti, had a large-scale history painting of ‘Boadicea Brooding over her Wrongs’ rejected by the Royal Academy; when Ruskin told her to stick to painting pheasants’ wings, she had a breakdown and began making spirit drawings. Howitt never showed her drawings in public, but Georgiana Houghton was more ambitious. After losing a much-loved sister in 1851, Houghton had sought solace in table-turning and during seances began to make watercolour drawings with complex biomorphic patterns under the reported guidance of various spirits, including Titian and Correggio.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in