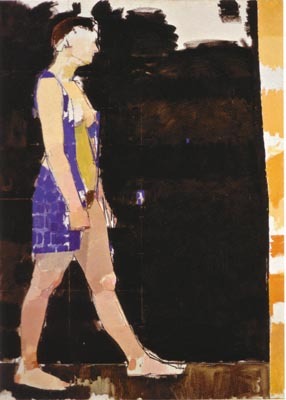

Euan Uglow: The Complete Paintings

Catalogue raisonné by Catherine Lampert; Essays by Richard Kendall and Catherine Lampert

Whether we know it or not ‘we crave the inexpressive in art’, Bernard Berenson wrote, as an antidote to the sensationalism of ‘the representational arts most alive, the cinema and the illustrated press’. He was writing about Euan Uglow’s great hero Piero della Francesca in an essay called The Ineloquent in Art, which came out in 1954, the year Uglow left the Slade, and made a deep impression on him: ‘There’s something about the title — the fact that there’s more force in controlled passion than in exuberant passion. That’s the idea I like. I like it slowly to creep out on you.’

Many people find it hard to connect Uglow’s painting with passion of any kind. He is famous for a particularly laborious method of painting which involved mathematical calculations, meticulous, even obsessive measuring, and complicated constructions of sighting wires and plumb-lines. The painting of a single figure could take up to seven years. The female nude was his great subject (together with portraits and still life), but the detached objectivity of his approach strikes some as being cold, unsensuous, even degrading.

His nudes certainly have more in common with 17th-century Spanish still life than they do with Titian — particularly the vegetables on strings of Juan Sanchez Cotán, who similarly based his compositions on mathematics and geometry. Uglow was said by his detractors to be unfeeling towards his models (‘when I’m painting I’m not interested in the model’s problems… I’m not trying to paint crucifixes’); he made them cut their hair, was furious if they got sunburnt, and enforced excruciating poses of such ‘brazen unnaturalness’ that some fell by the wayside, leaving paintings unfinished.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in