Manuscripts have something of the appeal of drawings. They bring you closer to the creative process. Even a copy adds something special to the text: an editorial twist, a decorated initial, a margin full of beasts or just a beautiful script in which every letter is fashioned by hand like no other. Manuscripts do more than convey information. Their creation calls for imagination, physical effort, a love of meaning and beauty. They are works of art in their own right.

I specialise in the most unpoetic kind of manuscript: administrative records of military and political history. But even they speak to us directly. ‘You fool — Norwich is inland’ is the supervisor’s marginal note on a 14th-century clerk’s suggestion that ships could be found there for the king’s service. ‘I can’t go on writing this stuff in this perishing cold,’ an accounts clerk complains on a windy plain in Flanders as he tries to record the expenses of Edward III’s first continental campaign.

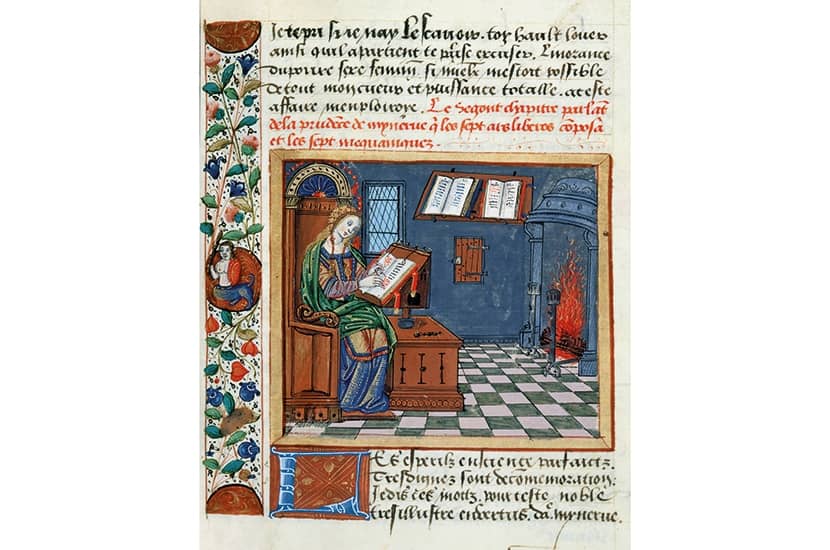

Many manuscripts perished in the tide of religious iconoclasm, along with the monasteries that housed them

Of all works of art, manuscripts are the hardest to exhibit. The bound volume lying flat beneath a glass pane, open at a single page, is an uninspiring thing. Even the beautiful reproductions available from specialist art publishers and on the websites of the greater libraries are an inadequate substitute for the real thing. They cannot convey the texture of the page, the variations of colour as the light falls on it from different angles, the creases and indentations, the shine of vellum and the roughness of parchment — all the things that make up the experience of holding the page or membrane in one’s hand. Mary Wellesley is a serious scholar, with years of experience of handling these fragile artefacts. Her achievement in this book is to convey something of these sensations to those who can only ever enjoy them vicariously.

Some of you may have read Christopher de Hamel’s unexpected bestseller, Meetings with Remarkable Manuscripts, published in 2016. This is a book in the same spirit. It is intensely personal. It wears its learning lightly. It chats easily and informally to the reader. It conveys a mass of arcane but fascinating information. But in other ways it is a very different kind of book. De Hamel wrote about dealers, collectors and librarians; Wellesley writes about creators, authors, scribes and parchment makers. Manuscripts establish a personal bond across the centuries between her and the men and women who made them. Few people have described the experience so eloquently.

The range is remarkable. We can read about the St Cuthbert Gospel, the oldest intact European book and testimony to the European dimension of English Christianity. Hidden in the coffin of the 7th-century saint, it was saved from the destructions of the Viking invasions and only found when the coffin was opened in the 12th century. It passed through many hands in England and abroad before coming to rest in the British Library. At the other extreme, the Paston Letters, a treasure trove of private correspondence between three generations of a 15th-century Norfolk family and their friends, clients and patrons, fetched up in the Public Record Office as part of the papers in a lawsuit. Most of the letters were dictated to a scribe, but the personalities of these men and women who died more than half a millennium ago still sing out from the page.

There are grand manuscripts, such as Henry VIII’s prayer book, in which the king himself is shown on several pages. It has never left the Royal Collection (now part of the British Library). At the other extreme stands the dictated autobiography of the eccentric and well-travelled holy woman Margery Kempe, which disappeared after its creation, only to be found in a jumble of family papers in the billiard room of a philistine country house in 1934 and saved from being thrown out by a passing houseguest.

The creation of manuscripts more or less ceased in the course of the 16th century with the invention of printing. In the same period, much of the accumulated stock of manuscripts made over the previous millennium was destroyed. They perished with the monasteries that housed most of them. Even in major centres of learning such as Oxford, only two of the 300 books donated to the university by that great bibliophile and patron of literature Humphrey Duke of Gloucester survived the tide of religious iconoclasm.

Will the printed book go the same way in the age of the internet? It is possible, but I doubt it. Manuscripts did not stop being made as soon as William Caxton set up his printing press at Westminster in 1476. They vanished once the printed book itself became a beautiful thing. Utilitarian reading of law books, scientific journals, manuals of accounting and the like will no doubt migrate to electronic formats. But they are not read for pleasure. Fiction, history, poetry, philosophy and other literary works are different. Reading them is not just an intellectual experience; it is a tactile, even an olfactory one, which no computer can replicate. To appeal to the full range of our senses, a text has to be a physical object, not a digital construct. Old books, whether manuscript or printed, are a special pleasure. ‘They have been handled and mishandled by so many people,’ Wellesley writes; ‘they are smudged with human stories.’ I do not suppose that Henry VIII ever curled up by the fire and read BL MS 2 A XVI as droplets from his nose fell upon the page. But he could have done.

‘In books we climb mountains and scan the deepest gulfs of the abyss,’ wrote the 14th-century bibliophile Richard of Bury, quoted here. A Kindle edition of this wonderful book is available, but those who understand what Richard of Bury was on about will prefer the print version.

Comments