This year’s Turner Prize has four winners rather than one. In a letter to the jury, the artists claimed that it would be wrong to adjudicate between the social causes championed in their art. So in the end, they split the spoils between them.

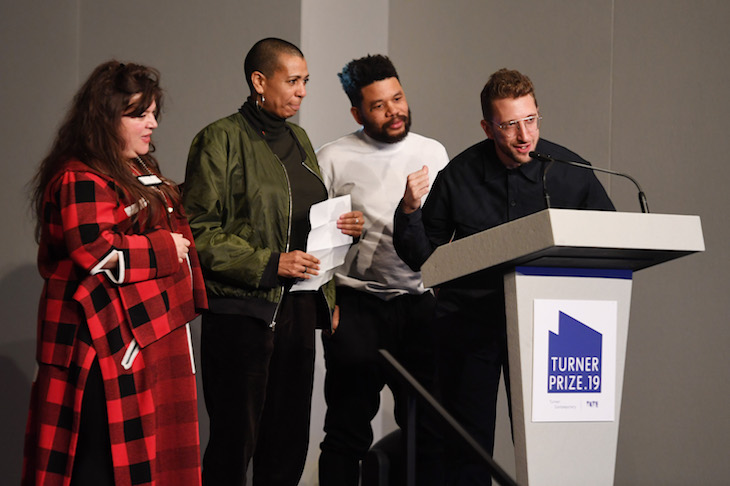

The judges had one job: to judge. Instead, they acquiesced to the candidates they were meant to be assessing. Instead of one name, poor Edward Enninful, the editor of Vogue, charged with opening the envelope at the ceremony in Margate, saw four: Oscar Murillo, Tai Shani, Helen Cammock and Lawrence Abu Hamdan.

‘Here’s something quite extraordinary,’ Enninful said, presumably off the cuff. ‘At a time of political division in Britain and conflict in much of the world, the artists wanted to use the occasion of the Turner Prize to make a strong statement of community and solidarity and have formed themselves into a collective.’

It’s a very noble idea, but is the Turner an art prize or a morality test? Did the artists not want to be judged on their creativity? And couldn’t the jury pick a winner by judging who had made the best art?

Even if you agree with the dubious premise of deciding the winning work based on its social value, why split the prize?

If the Turner panel were to have picked Cammock’s film, which stresses the role of women during the Northern Irish Troubles of the late 1960s, ahead of Shani’s vision of a post-patriarchal utopia, would that really suggest a political preference that denigrates the message of the runner-up?

Great art can make very strong political statements (think of Picasso’s ‘Guernica’, painted to highlight General Franco’s horrific bombing of the eponymous Basque town during the Spanish Civil War), but...

Britain’s best politics newsletters

You get two free articles each week when you sign up to The Spectator’s emails.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in