Since 2010, British police have shot dead 30 people. This works out at an average of around 2.1 people per year. In two consecutive years – 2012-13 and 2013-14 – not a single person was fatally shot by police in the UK. In 2023-24, the last period for which we have full data, it was two; for 2022-23, it was three. Which is to say that incidents where the British police kill people are vanishingly rare. It is highly unusual for the roughly 6,000 licensed firearms officers in England and Wales to use their weapons at all. Over the past decade there have been only 66 incidents where officers have fired their guns at people, even though armed police are deployed to around 18,000 incidents every year.

By way of comparison, about two people per year in the UK are killed by lightning, with 58 confirmed deaths in the 30 years before 2016. And only 5 to 10 per cent of lightning strikes on humans are fatal, meaning that something like 1,000 individuals were struck by lightning during that time.

Given that almost all armed police confrontations involve known criminals, terrorists or madmen, the average sane law-abiding Briton is far more likely to be struck by lightning than to be shot by the police. Indeed, the chance of such a person encountering an armed response team is effectively zero.

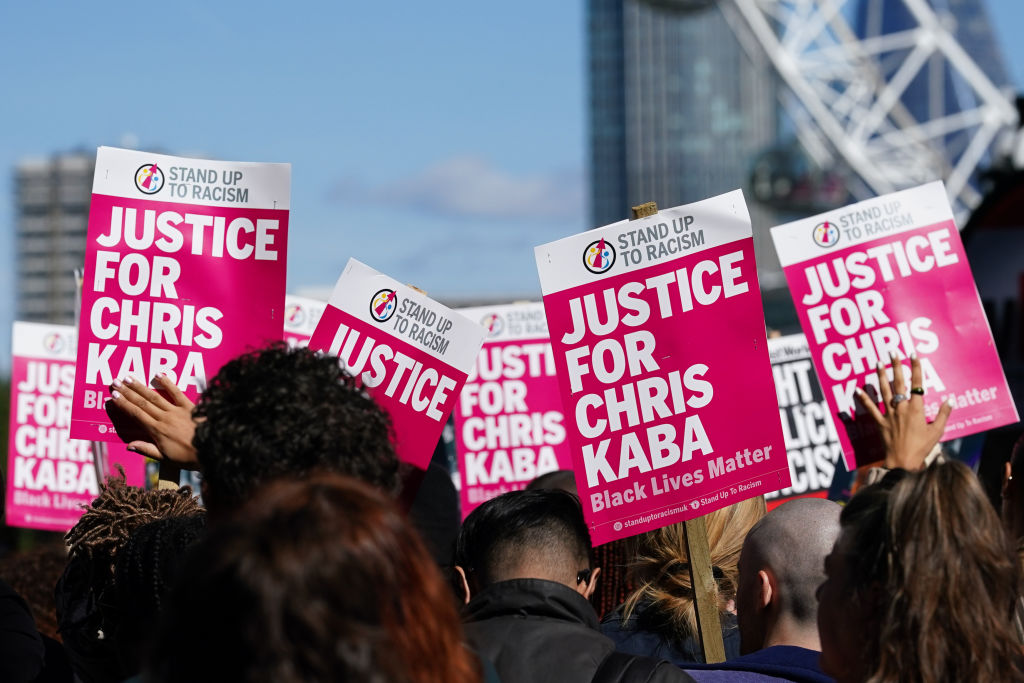

This is the crucial context for the Chris Kaba incident, in which a South London gangster was shot dead during a ‘hard stop’ after driving his car at armed police officers who were trying to arrest him. Sergeant Martyn Blake, who pulled the trigger, was acquitted of murder at the Old Bailey yesterday, more than two years since the shooting in September 2022. Campaigners have tried to insinuate that the British police are trigger-happy racial bigots, able to kill with impunity. But there is simply no evidence for this. At this point, belief in the concept of ‘institutional racism’ when it comes to the current police force, is for all intents and purposes a conspiracy theory.

The manifest weakness of the prosecution case against Martyn Blake – the jury deliberated for only three hours before returning not guilty – will surely lead many to ask why the case made it to court in the first place. The body-worn video footage seen by the jury, and now in the public domain, shows Kaba refusing police commands to surrender, and driving his large, heavy car at officers. It seems beyond reasonable doubt that – as contemporary media reports indicated – Blake was justified in considering Kaba a deadly threat to himself and others, especially in light of the fact that the car he was driving was linked to a firearms incident the previous day. Kaba was only 24, but had already spent time in prison for violence, and shortly before his death was suspected of involvement in an attempted murder. Tom Little KC, for the Crown, did his best with a threadbare brief, trying rather feebly to suggest that officers had not identified themselves appropriately, even though the footage shows that they did, in case Kaba hadn’t noticed the blue flashing lights and the large car in front of him with the word POLICE written on it.

Little also picked a few inconsequential holes in Blake’s testimony, but it was pretty thin gruel. Blake’s fellow officers testified that they had considered themselves to be under threat by Kaba’s actions, and one of them stated that he too had been on the verge of firing his weapon.

There are a couple of plausible theories for why Blake ended up in the dock on an indictment that no jury was likely to accept. One of these blames good old-fashioned cowardice. In this account, no one in the Met, or the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC), or the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS), wanted to take responsibility for deciding on no further action, and so the buck was passed to 12 good persons and true. If there were going to be riots or protests in response to Blake ‘getting away with it’, or career repercussions for those deemed insufficiently attentive to the alleged bogeyman of police racism, then of course offloading the decision was an extremely attractive prospect.

Then there is the even more worrying possibility that the Met, the IOPC and the CPS are institutionally sympathetic with the anti-policing and anti-law beliefs that animate groups like Black Lives Matter. The BLM ideology is essentially nihilistic insofar as it rejects the need for organised policing without offering any serious proposals for how to maintain public safety. It encourages racially-based hostility to whites and to other ethnic minorities. Support of its agenda is clearly incompatible with serving in organisations which are meant to uphold law and order, and to monitor police integrity.

The IOPC in particular has a track record of coming down very hard on individual officers who are doing their duty in difficult situations, and giving succour to those who thrive on racialist grievances. Just in the last two months, their judgment has been called into question by two rulings. In September, Southwark Crown Court quashed the conviction of PC Perry Lathwood for assault. Lathwood was originally convicted of this offence in May, after he mistakenly arrested a woman on suspicion of fare-dodging in July 2023. The IOPC had been instrumental in persecuting Lathwood, but when you consider the details, the Met Police Federation were surely right to call the initial conviction ‘erroneous and perverse’.

Two weeks ago, a second high-profile IOPC case unravelled. Two officers who had been sacked from the Met after a controversial traffic stop of the athlete Bianca Williams were reinstated by the Police Appeals Tribunal. The tribunal described the termination of the pair as ‘irrational’ and ‘inconsistent’.

The whole system tends to be cruel towards individual officers. The officer who shot the heavily armed career criminal Azelle Rodney during another ‘hard stop’ in 2005 spent a decade with the threat of prosecution hanging over his head, while various bodies considered his actions at excruciating length, before finally being acquitted of murder in 2015.

It is a difficult time for British policing, with forces facing criticism from all parts of the political spectrum. Like many conservatives I have my own severe reservations about how the country is being policed. But that does not mean that we should abandon all defence of the thin blue line against cynical and dishonest attacks. We cannot remain silent when vexatious prosecutions are brought against dedicated individual officers for murky political reasons.

Comments