Tribal rivalries have existed from humanity’s beginning and have fuelled the creation of every prestigious monument ever built. By the Age of Science we were building not pyramids but ironclads and submarines fighting for ascendancy at sea, expanding our empires in spite of an ever-growing movement for colonial independence. The Spanish-American war of 1898 added the United States to the list of great nations believing it to be their destiny, even duty, to bring their kind of progress to the world.

Many understood that achieving overwhelming technological power as a nation guaranteed that no antagonist would dare attack. Limited by agreements made after the first world war, Britain no longer ruled the waves. Like France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the USA, we saw aerial supremacy as our best means of extending and consolidating national influence. Britain’s empire had actually grown larger and more difficult to run. There were weaknesses everywhere. Transport and communications were paramount concerns of trade, administration, the military and national prestige.

Safety warnings were overriden, tests were cut short and weaknesses were actually patched over

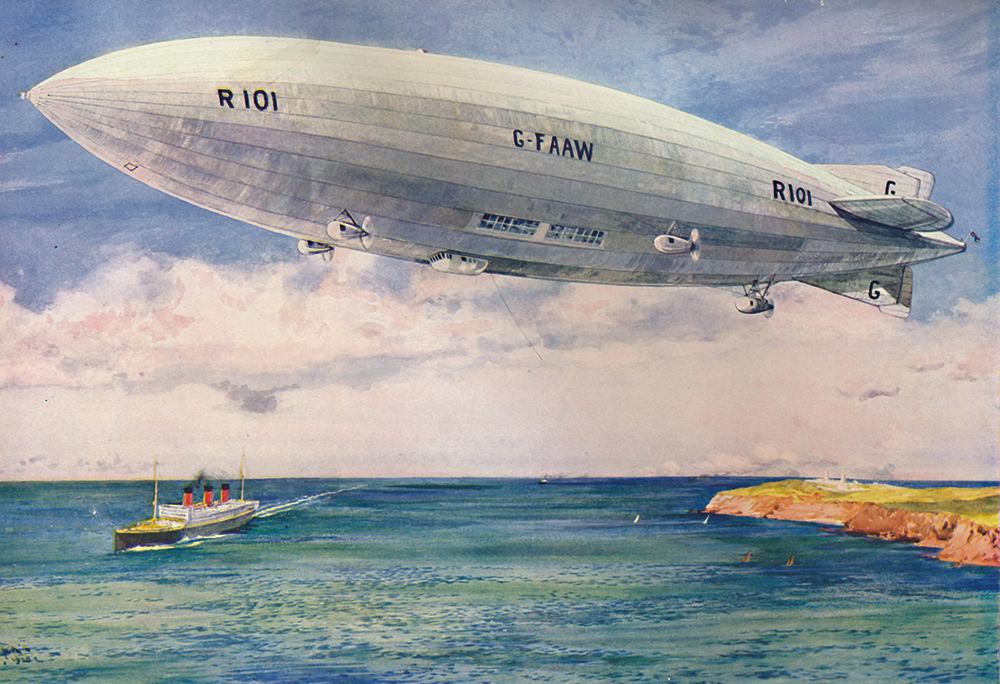

The airship race of the 1920s and 1930s carried that familiar mixture of visionary idealism, populist politics and wishful thinking which so often ended in tragedy. The explosion of the swastika-emblazoned Hindenburg in 1937 is the best known, but the years before the second world war, as countries rushed to launch successful lighter-than-air ships, saw many other disasters. Very few crashed without loss of life. Most took a substantial number of crew and passengers with them as they split in two, turned end-up, went down in flames or disappeared into the wastes of the polar ice. The only large ships to survive were withdrawn from service after dramatic test failures or the loss of sister ships. As S.C. Gwynne points out in this excellent account of perhaps Britain’s greatest imperial folly, not a single ship could pass an airworthiness test, and even ‘safe’ ships such as the Graf Zeppelin or Vickers’s ‘private’ R100 barely escaped disaster on many occasions.

The R101 was the dream of the charming imperial romantic Christopher Birdwood Thomson, who imagined a benign commonwealth held together by the power of mighty airships capable of carrying statesmen, goods and soldiers to any part of its far-flung lands. His fellow visionaries included the alcoholic daredevil G.H. Scott, our most experienced airshipman; Britain’s best navigator E.L. Johnston; and Michael Rope, R101’s designer. All of them believed that they had learned from the Zeppelins’ mistakes.

Their enthusiasm far outweighed their experience. They were fired up on Verne- and Wells-inspired serials in the likes of Modern Boy (whose long-running star was Biggles), where Britons consolidated their empire and saved the world by inventing great cigar-shaped flying machines. The Freudian appeal of those aerial monsters hasn’t gone unremarked, of course; but having experienced the euphoria of powered lighter-than-air flight, of seeing the detailed countryside passing slowly below, the only sound being the engines’ purr, I can vouch for the strong appeal of airship flight.

‘Kit’ Thomson, with his Romanian mistress, his taste for writing poetry, his Kiplingesque imperial idealism and his faith in scientific progress, was every inch the sophisticated 1920s clubman. His best friend Ramsay Macdonald was so fired by Thomson’s vision that he first made him a lord and then Secretary of State for Air in charge of the R101 project. Thomson had no practical experience of man-made flight. His R100 ‘rival’ was Barnes Wallace, later famous for his spectacular wartime inventions. R100’s hair-raising Atlantic round trip, in which she survived a number of near-disasters, was considered sufficient proof of the differently built R101’s ability to fly to India and back, the first of an intended mighty fleet connecting the British Empire at every point, the modern version of the ‘All-Red’ shipping route.

R101’s construction was rushed. With his eye on the viceroy’s job, Thomson’s wanted, unrealistically, to be in India and back on specific days. Safety warnings were over-ridden, tests cut short and weaknesses actually patched over. With no bad-weather experience, R101 took off on the evening of 4 October 1930 from Cardington, Bedfordshire, in terrible conditions, limped across the Channel, frequently out of control, went down 60 miles on the other side of Paris and burst into flames with the loss of all but four crewmen. No record of her last hours survives, there were few witnesses of the crash (recently proved to be the result of a snapped cable) and Thomson’s wonderful dream died with him. The R100 would be scrapped, and Britain would put her faith in Imperial Airways flying boats instead.

The building, and loss, of the ‘world’s largest flying machine’ was an example of imperial hubris, ignoring all realities and safety warnings and pushing ahead with a recklessness rarely known before. Similar tragedies would be repeated across the western world. Machismo and grand visions combined with a need for national reinvention, reflected in the dictatorships of Hitler and Mussolini. Later technological races, such as the production of flying boats and jet liners like the Comet, resulted in spectacular failures but only occasionally the same terrible loss of life. They too were symbolic of mankind’s folly – our haste to show off our tribal glory. At least by the beginnings of the space race nations had learned more caution in construction and greater concern for the lives of those caught up in the vision.

As a young journalist, I heard that America had lagged in the space race because of its engineers’ failure to build a ship resembling the streamlined craft gracing the covers of 1930s science fiction magazines. In recent years we have learned that successful airships can be built, but must be far less grandiose to be efficient. Nevertheless, we continue to dream of massive aerial liners progressing across our skies. Sometimes mankind’s imagination can still thoroughly trump reality.

Comments