In 1967, the unexpected worldwide success of Bonnie and Clyde blindsided the Hollywood film industry, which then spent the next half decade attempting to adapt to the changing tastes of the new youth audience it had apparently captured. No matter that the picture took a pair of vicious, sociopathic thrill-killers who in real life were about as appealing as the Manson family and reinvented them as glamorous Robin Hood figures, there was obviously money to be made, and the studios wanted a slice of it.

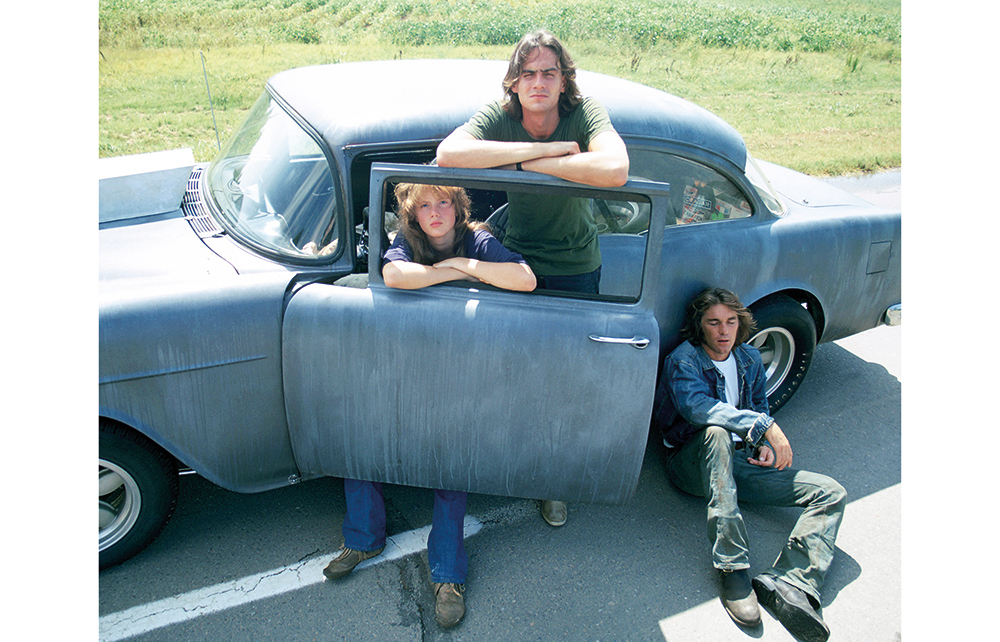

The road movies of the 1960s and 1970s were often modern-day westerns in disguise

While Peter Biskind’s 1998 study of the late 1960s and 1970s Hollywood scene, Easy Riders, Raging Bulls, covered a more disparate range of American films and subject matter, Peter Stanfield’s engaging and well-researched Dirty Real takes a specific look at a number of westerns and road movies that were often modern-day westerns in disguise. This was a time in which relatively young, often inexperienced directors were given a budget by recently appointed studio moguls sometimes not much older themselves. However, as Stanfield points out, despite a smokescreen of street credibility, the usual recipients of such largesse were not little known blue-collar figures from the underground film scene, but privileged and well-connected insiders such as Peter Fonda, the son of Henry and brother of Jane:

For so many of the new generation of film- makers, Hollywood was already home. They hadn’t strayed from the family hearth to pursue their dreams; they had no need to be picked out by a passing director. It was their world to inherit; the trick they pulled off was to suggest they had gained it by hard-scrabble labour, from experience earned on the road, with sweat and dirt honestly come by.

The dirt referred to here and in Stanfield’s title provides a core theme of the book, tracing the progress of films such as The Last Movie, Two-Lane Blacktop (both 1971), or Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (1973) which sought to show a grittier reality than that found in the average John Wayne movie, the actors themselves often smeared with grime as proof of their authenticity. It seems appropriate that this enthusiasm for the 19th-century concept of nostalgie de la boue re-emerged in the wake of the hippie movement, given that the 1969 Woodstock festival involved some 500,000 people spending several days in a rain-soaked cow pasture, wading around in mud and manure. The enduring myth of the festival was then cemented by Michael Wadleigh’s documentary film of the event, among whose technical crew was the future 1970s film auteur Martin Scorsese, working as second unit director and as one of several editors.

Woodstock occurred in the same year that Easy Rider became a worldwide hit, starring two hip young Hollywood insiders, Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda. Hopper directed, and the two of them co-wrote the script with Terry Southern. The film’s free-form tale of a pair of self-consciously anti-establishment drifters, together with its prominent rock soundtrack, greatly accelerated the studios’ enthusiasm for the kind of films Stanfield examines, not least Hopper’s own The Last Movie (1971). This quixotic, challenging tale, shot largely in Peru, bombed so thoroughly it almost finished the director’s career.

Box office success is of course no proper measure of a film’s worth – the highest-grossing picture in the US in the year that Hopper’s crew was labouring in the Peruvian jungle was the saccharine and critically mauled tearjerker, Love Story. However, what is under discussion here is the extent to which these films succeeded artistically on their own self-prescribed terms, their debt to earlier directors of the French nouvelle vague and the 1960s US underground scene, and how much of their professed authenticity and rebel stance was simply a pose.

Stanfield is very good at setting out the leading participants’ cases and then pointing out some of the perceived contradictions. When discussing Peter Bogdanovich’s majestic 1971 film of Larry McMurtry’s Texas novel The Last Picture Show, he devotes considerable space to the highly debatable verdict of the feminist author Rita Mae Brown (future screenwriter of 1982 slasher movie The Slumber Party Massacre), who dismissed it out of hand as ‘sentimental slop about white, male, small-town youth’ and ‘white men’s lies’. He returns to her opinions twice more in his narrative, but in this case and that of the other films examined here, his insightful stories of their origins only serve to make you want to watch them again.

That relatively brief window in which Hollywood attempted to make ‘underground’ pictures for mainstream audiences is well evoked by Stanfield, and in today’s Marvel Universe world, seems further away than ever. Two Lane Blacktop’s director Monte Hellman later wrote and directed the straight-to-video horror, Silent Night, Deadly Night 3: Better Watch Out! (1987). Easy Rider’s counterculture stars showed up in different fare of a less successful nature, Hopper in Super Mario Brothers: The Movie (1993) and Fonda in the live-action Thomas The Tank Engine adaptation, Thomas and the Magic Railroad (2000). But as Lou Reed once sang, those were different times.

Comments