Every operation starts the same way. Chlorhexidine scrubbed under nails, lathered over wet hands, palm-to-palm, fingers interlaced, thumbs, wrists, forearms. A soothing routine accompanied by the sound of water hitting a steel trough sink. Washing is an act of safety but also humility. It acknowledges a doctor’s capacity to cause disease as well as cure it. More than once I have thought of Joseph Lister — the father of antisepsis (killing germs) and forefather of asepsis (excluding germs completely) — as I perform this hygienic set-piece. Not that he would have liked the idea of me, his sister’s great-great-great granddaughter, studying medicine. Lister ‘could not bear the indecency of discussing with women the secrets of the “fleshly tabernacle”’, and sought to block their membership of the profession.

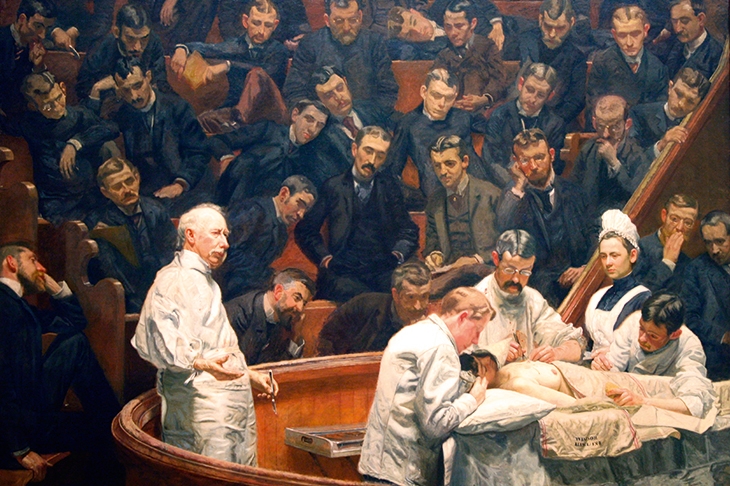

In the 1860s, much of the surgical establishment dismissed antisepsis as ‘hocus-pocus’. They were unwilling to believe that current techniques might actually be harming patients. Instruments were rarely cleaned between cases, surgical aprons stiffened with blood, and surgeons had been known to suck patients’ wounds in the middle of an operation. Professional assets included a firm fist that could double as a tourniquet, and the dexterity to flay flesh to the bone in seconds (even if a testicle or finger was collateral damage). A surgeon’s currency was speed and strength rather than sanitary practice.

Joseph Lister (1827–1912) — with his ‘indescribable air of gentleness, verging on shyness’, a stutter and almost ‘womanly’ concern for others — was not the obvious candidate to overhaul this filthy mess. Medicine didn’t run in the family. Devout Quakers, the Listers believed that homeopathy and divine intention were the best healers. Nevertheless, aged 17, Lister found himself in the overcrowded stench of central London embarking on a surgical education.

Lindsey Fitzharris has written a brilliant biography that embeds Lister in his medical moment.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in