Since art auctions were invented, they have served to hype artists’ prices. It can happen during an artist’s lifetime — Jeff Koons’s ‘Balloon Dog’ — or half a millennium after their death — Leonardo’s ‘Salvator Mundi’. And it can sometimes restore a lost reputation, as happened with Frans Hals.

When the picture now famous as ‘The Laughing Cavalier’ came up for auction in Paris in 1865, Hals was all but forgotten. A successful portraitist in his lifetime, he never made much money — with a wife and at least ten children, he remained a renter throughout his career — and after his death his reputation, overshadowed by Rembrandt’s, was tarnished by claims that he was a piss artist. In the 19th century the modernity of his style began to pique the interest of connoisseurs, but it was the bidding battle for the mystery ‘Cavalier’ (the ‘Laughing’ was added later) between Baron James de Rothschild and the 4th Marquess of Hertford that sent his prices soaring. When Hertford splashed 51,000 francs — more than six times its estimate — on the painting, Hals’s reputation was remade. Sir Charles Eastlake described the bidding as ‘spirited, then absurd’; the National Gallery failed to secure the picture, and it became the pride of the Wallace Collection.

Hals’s male patrons tend to be animated and jovial, their better halves stiff and down-in-the-mouth

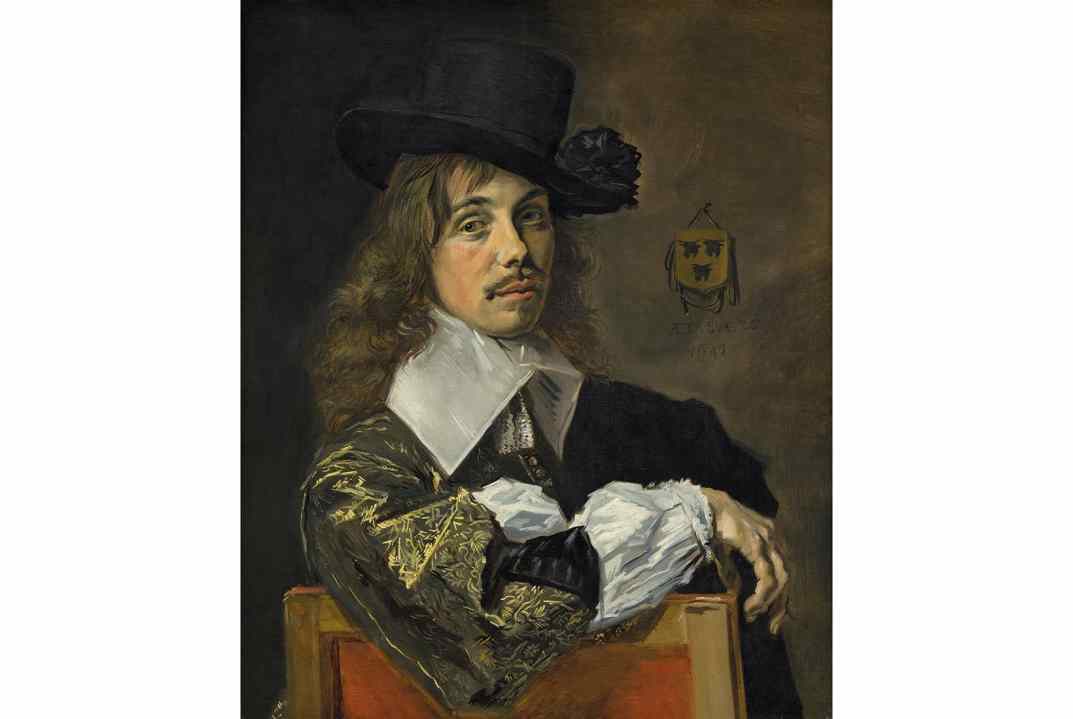

Now the Wallace has given Hals’s most famous painting an escort of 12 other portraits from international collections, inviting us to place it in context. Starting with an early formal portrait of a sombre man with a skull and ending with a bravura painting of a raffish individual in a rakish hat, the baker’s dozen of Dutch burghers in Frans Hals: The Male Portrait are unapologetically white, middle class and male. Given the dreariness of Hals’s female portraits, this is a relief.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in