Pity the poor curators of major exhibitions struggling to find fresh takes on famous masters. The curators of Tate Modern’s new Cezanne blockbuster have begun by dropping the acute accent from his surname, apparently a Parisian affectation not in use on the artist’s home turf. Anticipating grumbles about another major exhibition devoted to a dead white male artist, they have emphasised Cezanne’s outsider status by painting him as a provincial from Provence. It was a role the artist liked to play in Paris, once famously excusing himself from shaking Manet’s hand on the grounds that he hadn’t washed in a week.

Cezanne’s peers put their money where their mouths were, creating an artists’ market for his work

With or without his accent, Cezanne remains French. He was in fact the only full- blooded Frenchman among the three great pioneers of post-impressionism, Van Gogh being Dutch and Gauguin boasting Peruvian descent. He was also, coincidentally, the only one of the three to emulate the masterworks in the Louvre. Not content with hitching a ride on the impressionist bandwagon, the artist from Aix ‘wanted to make of impressionism something solid and enduring like the art of museums’. In the process, paradoxically, he set in motion the modernist revolution that led to cubism: Picasso acknowledged him as a ‘father’ and kept a chunk of Mont Sainte-Victoire as a relic.

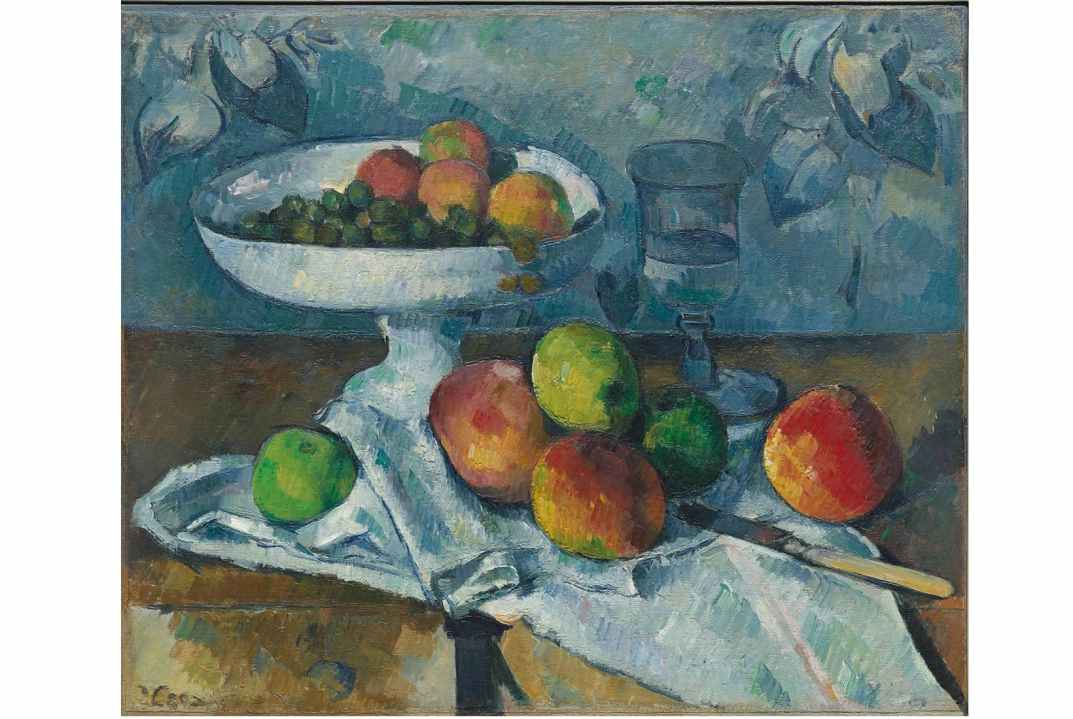

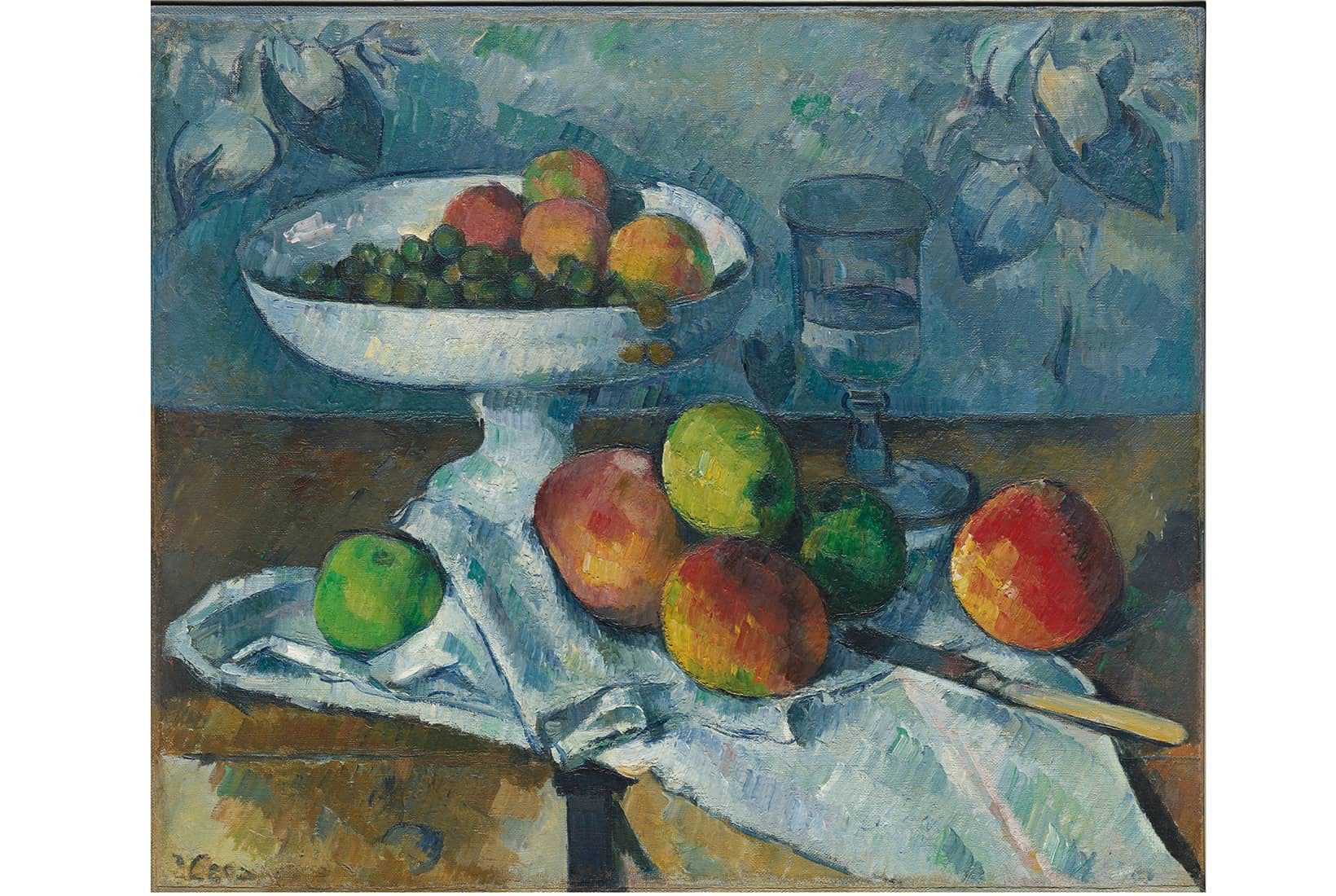

Cezanne is what is known as ‘an artist’s artist’. That doesn’t mean he’s difficult, it means he’s good. If you want to find the best artists in any generation don’t ask the critics, ask their peers. Cezanne’s peers put their money where their mouths were, creating an artists’ market for his work long before his breakout exhibition with Vollard in 1895. Gauguin owned six Cezannes by 1883; the ‘Still Life with Fruit Dish’ (1879-80) in the exhibition was his prize possession.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in