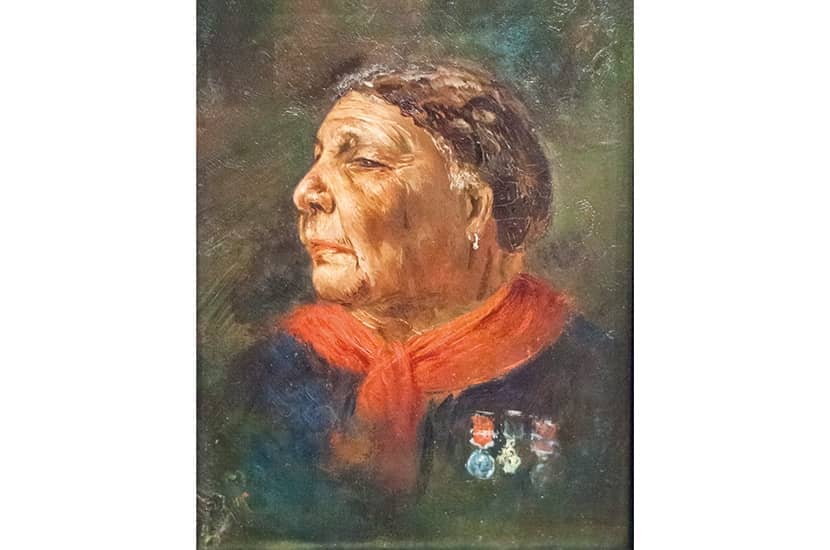

Who would have thought that a statue of a West Indian-born nurse in south London has a role in today’s culture wars? Unveiled in 2016, it stands three metres tall outside the great teaching hospital, St Thomas’, and depicts Mary Seacole, an extraordinary Creole woman who was loved and renowned for giving succour to British troops, first in her native Jamaica and then in Crimea during the bloody and prolonged war with Russia of 1853-6.

It is controversial on two main counts. First, it stands on hallowed ground at the hospital where Florence Nightingale pioneered nursing as a profession after returning from Crimea. Critics deemed it wrong to site a likeness of Seacole in Nightingale’s backyard, because she had no connection with the place and only the original Lady of the Lamp was a nurse in the modern sense. In comparison, say these detractors, Seacole was a charlatan, a camp follower who acted as little more than a sutler, selling food and drink to (mainly) officers, and who boosted her reputation by publishing memoirs which may well have been ghost written.

The first charge hints at elitism: it suggests Seacole was an amateur in the increasingly specialised world of medicine. Certainly she was dismissed by the inflexible Nightingale. But that only highlights a second theme of racism. Seacole was a mixed-race woman who practised a particular sort of Jamaican medicine centred on herbs and potions, backed by tender loving care.

Seacole was given short shrift by officialdom in London, and then by Nightingale in her hospital in Scutari

Over the past quarter century, as Seacole has been rediscovered, she has become a political touchstone. Since being voted Britain’s greatest black person in 2004, she has again been widely feted (fuelling the campaign which led to the statue a dozen years later) but also translated into an often contentious symbol of immigrants making their way in an inhospitable society.

Helen Rappaport has set about bringing clarity to Seacole’s life.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in