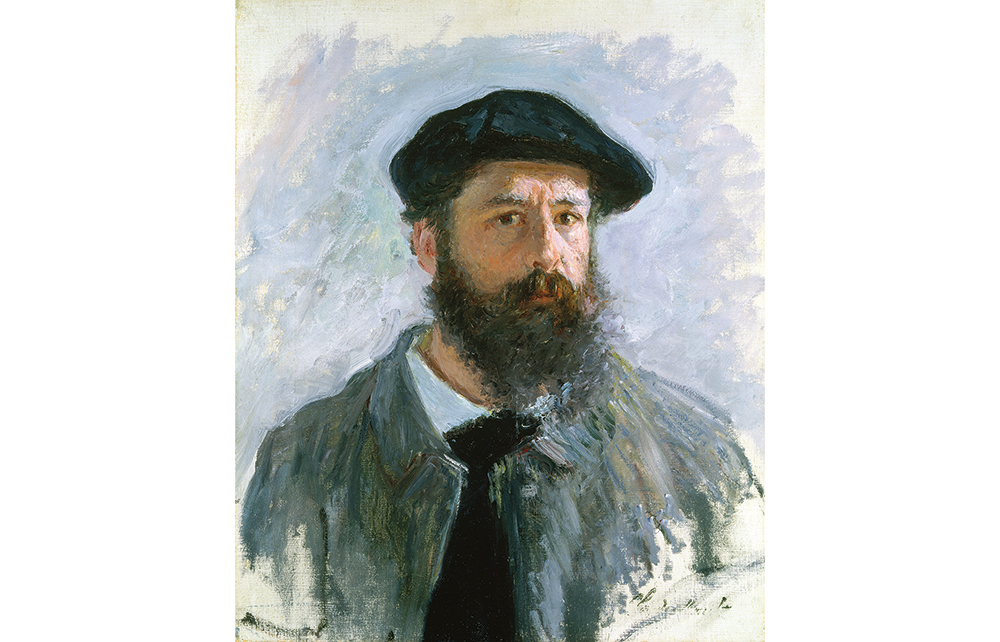

There have been some really good biographies of artists over recent years and what distinguishes the best of them is their sense of context and a lucid prose free from the jargon of the art historian. In the end, of course, any work of art has to be able to stand by itself, but for Jackie Wullschläger her appreciation of Monet’s paintings has been immeasurably deepened by her sense of the man behind them.

‘My approach,’ she writes, ‘stems from the belief that painters transform the raw material of experience into art’, and that material, both the familiar external events and, more illuminatingly, the inner man, is what she gives us here.

Monet’s compulsion to paint would last his whole life, accompanied by a questing need to innovate

Oscar Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840, the son of a marine merchant. His father’s business interests soon took the family to Le Havre and it was there that the young Monet – known by his first name, Oscar – grew up in a comfortable bourgeois environment. In 1857, however, everything went wrong. His mother died and his father’s business failed. It would be many years before Monet knew financial security again. Even when acknowledged as an artist of some repute, he would still be imploring relations, friends, dealers and supporters for money to cover outstanding accounts, rent arrears and even food. The time when he was able to earn more than 270,000 francs in a single year was a long way off.

The trajectory of his career began with caricatures. As a boy he drew humorous sketches of local figures in Le Havre, shown in a stationer’s shop window. They caught the eye of the artist Eugène Boudin who encouraged the 17-year-old to accompany him on open-air painting expeditions, which in turn led to art school in Paris.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in