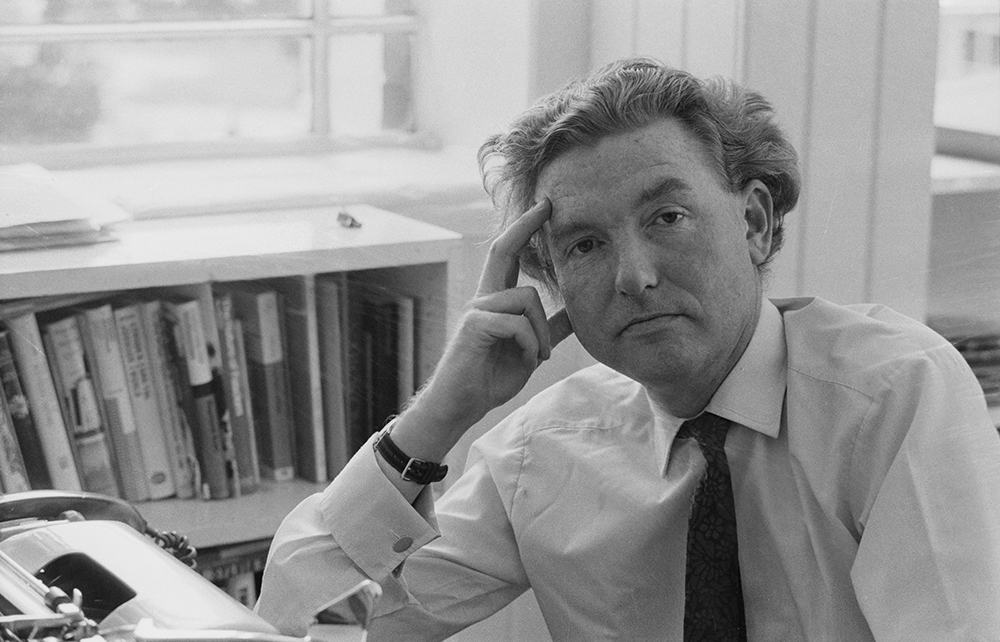

Paul Johnson – who was a columnist for The Spectator from 1981 to 2009, and who died last week – did not merely write history: he helped to make it. His first book, The Suez War, published in 1957 with an introduction by Nye Bevan, documented the evidence that eventually led to the resignation of the Prime Minister, Sir Anthony Eden. In Buckingham Palace six decades later, Prince William startled him by asking about Suez. Afterwards my father asked: ‘Who was that well-informed young man?’

A demonstration against the government over Suez was also the occasion for him to get back together with the brilliant and beautiful Marigold Hunt, whom he had once invited to the Ritz but stood up. I was only the first of the results of that reconciliation, soon to be followed by my brothers, Cosmo and Luke, and sister Sophie.

Many of my contemporaries have vivid memories of visits to our home in Iver. There my father presided over idyllic Sunday lunches, improvising quizzes for us children and entertaining the Worsthornes, Frasers, Howards, Stoppards, Amises, Gales and countless others with conversation and jokes that flowed and gurgled like a bubbling stream. When the talk turned to politics, he could be combative. We children didn’t like that. Aged about six, I tackled him: ‘Daddy, why do you go on and on about Mr Wilson?’ ‘Why do you go on about the Daleks?’ he replied.‘The Daleks are important,’ I said. After lunch there were walks in Langley Park, culminating in the hunt for sixpences, hidden in a giant hollow tree where (he claimed) the Great Train Robbers had stashed their loot.

My recollection of him taking me to London on my seventh birthday is a joy: riding in a taxi, visiting the New Statesman office as the editor’s son, and then to Bertorelli’s for lunch, where he introduced me to Vicky, the great cartoonist, who was not much taller than I was.

Having made his mark as an angry young man, he morphed into an angry old one

He seemed to know everyone. When I was puzzled by my part in a school play by J.B. Priestley, he suddenly said: ‘Let’s ring old Jack up and ask him.’ Next minute, I heard an aged voice with a Yorkshire accent saying: ‘Oh yes, Time and the Conways. Damn good play, that. What’s the problem?’

My father had the good fortune to live in a time when journalists were enjoying a kind of renaissance. He liked to say that he had met every British prime minister from Churchill to Blair and every American president from Eisenhower to George W. Bush. It may even have been true.

The apotheosis of the journalist as politician came only in the next generation, when one of his former editors at The Spectator entered Downing Street. In old age, Paul had his share of recognition, most notably when he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from George W. Bush.

His CBE was ‘for services to literature’. The citation is apposite: none of the proximity to power would have meant much if he had not been the master of English prose that he was. Stephen Glover, an exacting critic, wrote that he was incapable of writing a dull sentence. Posterity is a harsh judge of journalism, but his best work will still be read when his detractors are forgotten.

Paul was no stranger to dangerous liaisons, but he had one that proved to be lifelong – with Clio, the muse of history. As a popular historian, he was often belittled by less popular academics. It is true that he relied on printed sources, but few could match the breadth and depth of his erudition. Sir Noel Malcolm tells me that as a reviewer he was staggered by the range of material deployed in this vast body of work, particularly as my father never used researchers.

‘He is at his best when angry,’ declared an anthology of New Statesman writers in 1963, apropos of his notorious review of Ian Fleming’s Dr No, ‘Sex, Snobbery and Sadism’. And, having made his mark as an angry young man, he morphed into an angry old one. The public Paul Johnson presented a pugnacious face to the world. Yet when he let down his guard, the private man was loyal, magnanimous and deeply vulnerable.

Like the apostle after whom he was named, Paul had more need of redemption and forgiveness than those who already fancied themselves saints. Hence he held fiercely to his faith, the traditionalist Catholicism of which his mother was his exemplar. He prayed, if possible in church, every day of his life.

He relied heavily not only on faith, but on friends and family. His inner demons tested all three. Drink made him a monster; infuriatingly, even in its grip, his work rate seldom slackened. Only the realisation that, unlike Churchill, alcohol was taking more out of him than he took out of alcohol drove him to give it up (with rare lapses) in his last few decades.

Yet Paul also had a capacity for love that was inexhaustible. Friends, of both sexes and of all ages, were treasured all the more if they could not follow his political peregrinations. He was generous to, and inordinately proud of, the burgeoning tribe of children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Though Paul gave Marigold ample grounds for not standing by him, their marriage endured for 65 years – the flying buttress which held up the entire cathedral of his work.

He was also generous to young journalists whose careers he encouraged, to students at Taunton College to whom he donated his art library, and to all those – from princesses and prime ministers to friends in need or in despair – who found their way to his door. To him, they were all equal before God and so in his esteem as well.

After I had followed in his footsteps to Magdalen College, Oxford, to read history, he treated me too as an equal. Now it was I who introduced him to men he admired: the medievalist Sir Richard Southern, Professor Friedrich Hayek, and the raucous Norman Stone.

Later still, when our careers overlapped in the world of journalism, he would greet me cheerily with: ‘What news on the Rialto?’ He made sure that I never felt overshadowed. Only at the end of his life, when his world had shrunk into the beloved library that became his sickroom, did my dear old father feel able to say: ‘I love you very much.’

Comments