Generalisations about national characteristics are open to question. Nevertheless, the overwhelming impression one gets from reading the major works of English literature, or from studying the famous English men and women of politics, the military or the academic world, is that the English have not been an especially religious lot. Or, if you think that a strange judgment of a nation that produced the finest Gothic cathedrals in Europe and the hymns of Charles Wesley, then you could rephrase it and say that they have not generally worn their religious feelings on their sleeve. Jane Austen’s hilarious novels do not quite prepare us for her letters in which she confesses her sympathy for evangelicalism. The novels are not only wonderful; they seem the quintessence of what we would like to think of as English.

Shakespeare describes almost all the emotions except the religious. Isabella in Measure for Measure is almost the only overtly religious character in the entire oeuvre. Dickens was in favour of Christmas and being kind, but his Life of Christ is really a bit of secular sentimentalism.

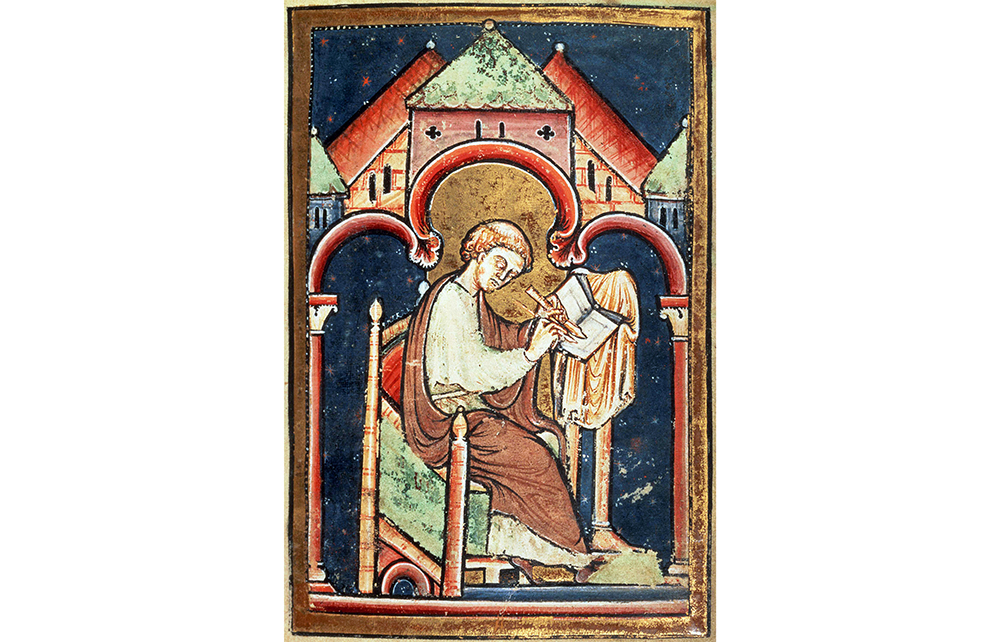

Undeterred, Peter Ackroyd has undertaken to tell the story of the English soul. Inevitably, therefore, it omits Shakespeare and John Locke and Dickens and William Cobbett. It is not a continuous narrative but a series of thumbnail sketches of some of the figures in English religious history, starting with the Venerable Bede, taking us on a breezy tour of the medieval mystics Julian of Norwich and Margery Kempe, and whizzing through the cast list of Archbishop Laud, George Fox, John Bunyan and Cardinal Newman before we reach the 20th century.

Ackroyd wrote a brilliant book about T.S. Eliot, whose Four Quartets were written when that austere American had become not merely a British citizen but a self-confessed monarchist and Anglo-Catholic.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in