The second passport used to be a backdoor: a legal hack for the well-advised, well-connected or well-heeled. You could acquire nationality in a country you’d hardly visited, without necessarily even speaking the language, and still find yourself welcomed with open arms – or at least waved through the fast-track lane at immigration. But that game is ending. More and more governments are closing the door on tenuous ancestral claims and pay-to-play citizenship. Whether through lineage or liquid assets, the old tricks to get a second passport no longer work. Nationality is being redefined – not as a loophole, but as a bond.

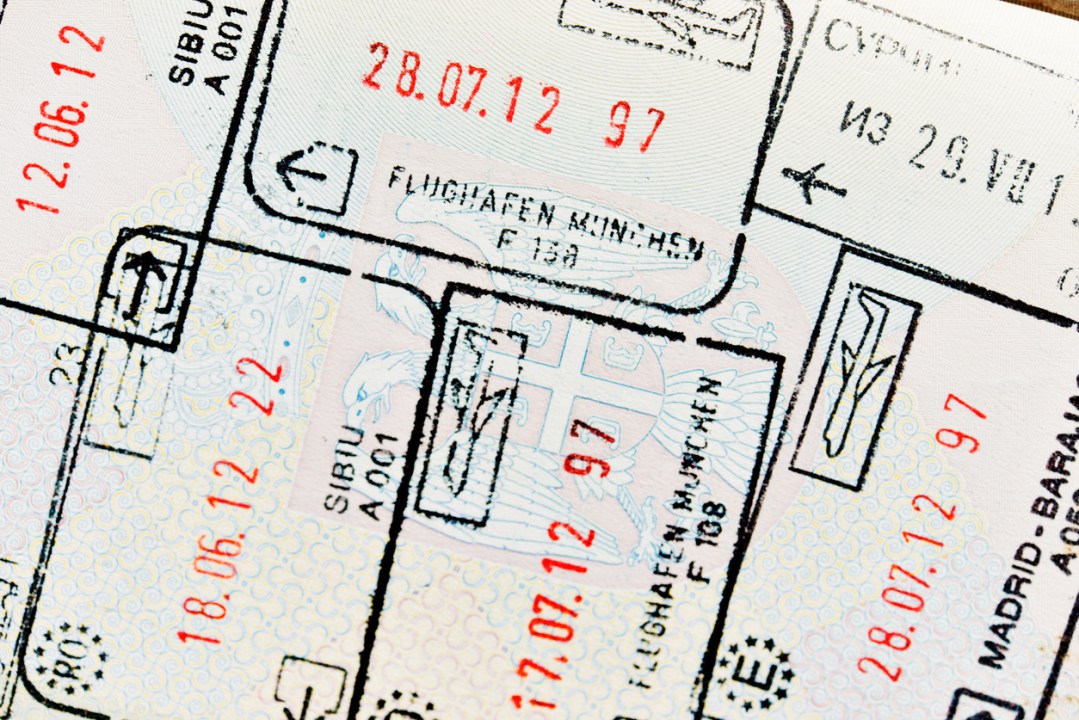

The appeal of a second passport has always been practical. For Britons, Brexit turned the post-Brexit navy passport into a travel straitjacket. The right to live or work across the EU vanished overnight. Meanwhile, the wealthy from countries such as India, Nigeria, Russia, China or Pakistan – stuck with passports that require visas for nearly everything – turned to Caribbean citizenships as a shortcut to global mobility. The point wasn’t loyalty to a country; it was access. Jonathan Miller, writing in this magazine, ditched his ‘useless’ British passport for an Irish one, largely because it opened more doors. For the past few decades, a passport has been less a marker of belonging than a laminated signal of status. Some treat theirs like a badge of prestige. Others collect them – I have a friend with four passports. Convenience trumped identity.

Italy has had enough. From now on, only those with a parent or grandparent born in Italy can claim citizenship by descent. Until earlier this year, the rules were absurdly loose – anyone could apply for an Italian passport who could prove descent from an ancestor going all the way back to Italian unification in 1861. In South America, entire businesses sprang up to manufacture Italian citizens by the busload. Italian consulates were overwhelmed, choking on the paperwork. Between 2014 and 2024, nearly 1.8 million people living outside Italy received Italian passports, most of whom had no language, cultural or geographic connection to the country. Calling time last month on the farce, Foreign Minister Antonio Tajani said that applying for an Italian passport is ‘not a game […] that allows you to go shopping in Miami’.

The modern passport is a bureaucratic descendant of something far older – a letter of safe passage from one city-state to another, vouching for the bearer’s decency and good conduct. The British passport still carries a faint echo of that tradition. It requests, in the name of His Majesty, that the bearer be allowed to ‘pass freely without let or hindrance’ and be given ‘such assistance and protection as may be necessary’. Somewhere between Renaissance Italy and the Schengen zone, that dignity was lost – replaced by biometric scans, visa quotas and, until recently, chequebook citizenship. At the outer fringe, novelty services now offer to print up passports for entirely imaginary countries – complete with your chosen flag, title and national motto. For the right fee, anyone can be a prince of nowhere.

Italy’s decision to tighten the rules is part of a broader trend. The once-popular golden passport schemes, which allowed the wealthy to purchase citizenship, are facing scrutiny. The OECD has warned about the risks of ‘identity laundering’ through these schemes, where individuals acquire new passports to conceal their origin or bypass financial transparency rules. Malta’s Individual Investor Programme, which allows anyone prepared to invest €750,000 and spend 12 months in Malta to become the proud owner of a brand-new EU passport, has faced criticism from the European Commission over concerns of money laundering and corruption. Despite revising the programme with higher investment thresholds, Malta has now suspended applications from certain countries. Pressure is building for them to drop the programme entirely.

Cyprus terminated its Cyprus Investment Programme in 2020 following reports that passports were handed to individuals who failed to meet the necessary criteria, including some with criminal records. This led to the indictment of several high-profile politicians and highlighted the potential for abuse in such schemes.

For the past few decades, a passport has been less a marker of belonging than a laminated signal of status

The Caribbean nations, long known for their citizenship-by-investment programmes, are also under pressure and have been tightening their policies. Grenada, for example, introduced a ‘citizenship by invitation’ initiative, selectively inviting only a limited number of ‘hand-picked’ investors who can contribute ‘significant entrepreneurial innovation’, marking a departure from open-door policies whereby they simply gave a passport to anyone who came along with enough money. Meanwhile, the European Union revoked Vanuatu’s visa-free access to the Schengen area over inadequate background checks.

Even countries such as Portugal and Ireland, which offered golden visa programmes granting residency to investors with a pathway to citizenship, are now backing away. Portugal’s programme has encountered significant processing backlogs, with nearly 900,000 immigration cases pending as of early 2025, leading to delays and legal challenges from applicants. Ireland, meanwhile, terminated its Immigrant Investor Programme in 2023, reflecting a shift towards more stringent immigration policies. Much of the investment in Ireland under the programme came from China.

This tightening of citizenship laws is not confined to investment schemes. Countries are also revising residency requirements to qualify for naturalisation. In January, Sweden proposed extending the minimum residence requirement for citizenship from five to eight years, alongside the requirement for applicants to demonstrate an ‘honest way of life’ and financial self-sufficiency. Denmark and Finland have announced similar measures, emphasising integration and genuine connection to the country.

For years, citizenship has been sold like a designer handbag. A Caribbean passport offered visa-free access to Europe. An Italian great-grandparent opened a backdoor into the EU. A few million euros could turn a Russian oligarch into a proud Maltese patriot. But the loopholes are closing. Governments are reasserting control. Nationality is being reclaimed not as a commodity, but as a connection. The message is clear: citizenship is not a lifestyle choice. It’s a bond – and bonds are earned.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in