Geography, climate, economics and nationalism are often seen as decisive forces in history. In this dynamic, original and convincing book Dominic Lieven considers emperors and their dynasties as motors of events.

Defying constrictions of time and space, ranging from Sargon of Akkad, the ruler of what is now northern Iraq (r. 2334-2279 BC), to the Emperor Hirohito of Japan (r. 1926-89), he believes that ‘for millennia, hereditary sacred monarchy had been the most desirable and successful form of polity on Earth’. (Inhabitants of city states, from Athens to Venice, might not have agreed.) Emperors could create and extend states more easily than impersonal forces, as Lieven shows in chapters on many different empires, from China to Austria. Emperors ruled heaven as well as Earth: they protected Buddhism in India, chose Christianity for the Roman empire and Shia Islam for Iran.

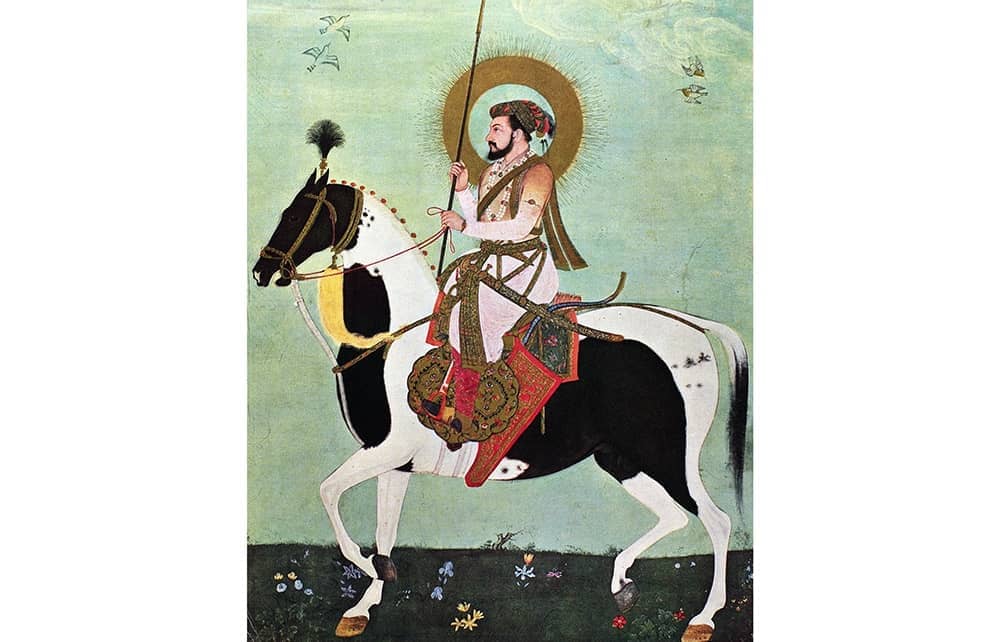

An explosion of books on monarchs, courts and dynasties has transformed history in the past 40 years, and Lieven has read most of them. He believes in a science of empires, which reveals certain ‘constants about human beings and political power’: the history of empires is a subject as important as economic or gender history. Lieven compares the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb with Stalin, and finds parallels between the Austrian and British empires in their aggressive reactions towards nationalist challenges.

Not until about 1900 did European royal families stop marrying first cousins

Succession struggles, he also shows, were among the most frequent causes of conflict. The Sunni-Shia split in the Arab caliphate (which had created an empire stretching from the Pyrenees to the Himalayas in less than a century) was not only theological but also ‘the most important monarchical succession struggle in history’, between the Prophet’s cousins and his descendants. Divisions among the heirs of Charlemagne helped split ‘Europe’s Carolingian core’ into states which eventually became France and Germany.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in