What are now called ‘fiscal events’—the Budget and the Autumn Statement—have become the biggest dates in the Westminster calendar. The Chancellor lights up the landscape with political pyrotechnics. There are attempts to bribe prospective voters through tax and spending changes, a litany of pork-barrel projects designed to help individual MPs, and fiendishly complicated schemes no one expects. But with the Treasury under new management, this will all change on Wednesday.

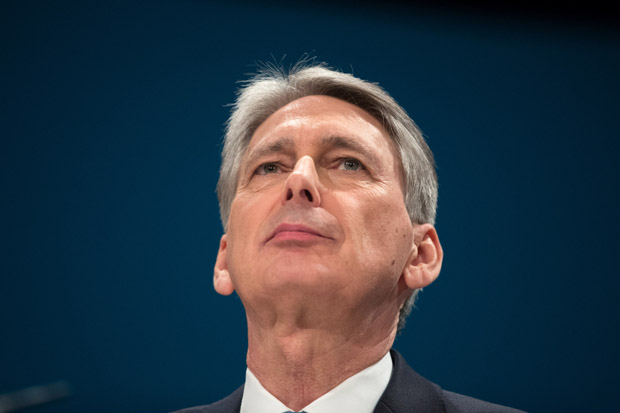

Philip Hammond is the least political Chancellor Britain has had for quite some time. The two longest-serving incumbents of recent times, George Osborne and Gordon Brown, doubled up as electoral strategists whose fiscal policies were informed, above all, by political aims. Hammond is different: he does not see this job as a stepping stone to another. Addressing Tory MPs recently about his plans for the Autumn Statement, he mentioned Labour only once in more than an hour.

But the limits to his ambition, and his dislike of the limelight, shouldn’t blind us to his importance. He has already made it clear privately that if the economy grinds to a halt and he needs to introduce a fiscal stimulus, he would rather embark on an infrastructure splurge than cut VAT. Hammond’s logic is that with infrastructure spending you have something left to show for it afterwards — whereas with a VAT cut (Alistair Darling’s policy after the crash) you simply boost consumption.

His new approach raises the question of how he will deal with the cost-of-living squeeze which even some of his closest allies think is coming down the track. If the pound’s fall in value pushes inflation up and wages fail to follow suit, then disposable incomes will be hit badly. The ‘just managing’ classes, whom Theresa May promised to help, might start to ask who stole their recovery.

Might this economic pain make voters turn against Brexit? And might this lead to pressure for the UK to remain inside both the single market and the customs union? These questions are being asked by several pro-Remain Tory MPs, including some in the government, but it looks unlikely. Theresa May has promised control over EU immigration, which is hard to square with single-market membership. And what’s the point of leaving the EU but staying in the customs union? It would stop the UK doing trade deals with other, non-EU countries — removing one of the main reasons for quitting. The most likely UK government approach on the customs union is to leave it then try to opt back into it in various sectors, such as car manufacturing.

Many Brexiteers regard Hammond as worryingly gloomy. They complain that he dwells on the negatives of leaving the EU and fear that his pessimism about the economy might become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Hammond himself believes that the most important thing is for him to maintain his credibility. If he declared everything to be rosy and the economy then stalled, he argues, his credibility as Chancellor would be shot. His friends say that if he asks difficult questions about Brexit, it doesn’t mean he is trying to block it. It just means he’s ensuring things are done properly.

But one thing Hammond should start doing is talk about the government’s options if there is no exit deal with the EU. He should make clear that the UK will not be passive in these circumstances and will enact radical measures to improve competitiveness if we are driven back into reliance on World Trade Organisation rules for our trade with the EU.

The government should, for instance, say that it will seek a deal to ensure the right of UK financial institutions to operate within the single market. But if that cannot be achieved it will take immediate steps to make the UK a more attractive place to base a bank. It will hack away at needless regulations such as the cap on bankers’ bonuses and scrap the corporation tax surcharge that banks currently have to pay. And it needs to get this message out soon, because banks will start considering whether to relocate parts of their operations in the new year. These measures are exactly what the French fear we will do, so will tend to make a UK-EU deal on financial services more likely.

Hammond is not a natural cheerleader, but he needs to be careful that he doesn’t come across as the government’s Eeyore. A chancellor can’t create consumer and business confidence through sheer force of personality. But if Hammond looks and sounds permanently downbeat, there is a risk that he creates the impression that Brexit Britain’s long-term prospects are nothing to smile about. He needs to counter that.

One way would be to emphasise the success of the British tech sector. Hammond recently told Tory backbenchers that both Bill Gates and Google’s Eric Schmidt believe the UK is ahead of Silicon Valley in developing both artificial intelligence and the internet of things. This is an astonishing achievement and one that Hammond should be shouting from the rooftops. Coming from him it would be authentic — and a reminder to voters and international investors of the UK economy’s bright medium-term prospects.

Most of the attention in the run-up to next week’s Autumn Statement will focus on housing. Hammond, a large part of whose personal fortune comes from property development, is keen to get more homes built; he regards it as one of the best ways to boost the economy in the short term and one of the most important structural changes to be made for the long term. He will also publish a housing white paper proposing various changes to the planning laws. He clearly thinks that the coalition’s efforts to overhaul them in the last parliament were inadequate.

The UK economy has performed far better than the Treasury feared since the Brexit vote. But Hammond will want to keep in reserve the possibility of a fiscal stimulus should the economy hit the rocks. So expect him to present a new set of more flexible fiscal rules that will let him step in if the economy needs it. His success or failure as a Chancellor, will, ultimately, be judged on the effectiveness of these rules.

Comments