Za in Ukrainian – and other Slavic languages – means ‘Beyond’, and porohi means ‘the Rapids’; so Zaporizhia stands for ‘the place beyond the rapids’. It a nice irony that the place, whose threatened nuclear power plant has put it in the headlines, is connected to one of Europe’s most venerable historico-geographical sites.

The Dnieper rapids rank with other spots, like the Bosphorus or the ‘Pillars of Hercules’ at Gibraltar, where pre-historic travellers were presented with an emotional rite of passage from one sphere of the world to another. At the start of the Viking age, the rapids still constituted the main obstacle to primitive voyagers, who aimed to transit from the Baltic to the Black Sea – through the heart of continental Europe to the Mediterranean. Two hundred miles above the Dnieper’s mouth, nine separate rows of massive granite outcrops interrupted the flow of water, creating a series of lakes, rocky ridges, defiles and waterfalls that made navigation near-impossible. This formidable obstacle was finally overcome in the ninth century by a party of Vikings known as Varangians, who thereby established a regular trade route from their native Scandinavia to Byzantium. In the process, one of their number, Rurik, founded a ruling dynasty who took Kyiv as their capital and created the early mediaeval Varango-Slavic state of Kyiivan Rus’. Sometime later, the rapids hosted the Sich or ‘island stronghold’ of the Cossacks.

Kyiivan Rus lies at the heart of the ongoing historical dispute between the followers of Vladimir Putin and his Ukrainian adversaries. Putin maintains that Rus – a contemporary to Norman England – was Russian. The Ukrainians say that Rus had nothing to do with ‘Russia’, which is a state and concept created centuries later by Moscow. Most scholars agree that Rus, whose Latin name was Ruthenia, gave rise to the three East Slavic nations of Ukraine, Belarus and Russia. But Putin wants to insist that only one nation exists, not three.

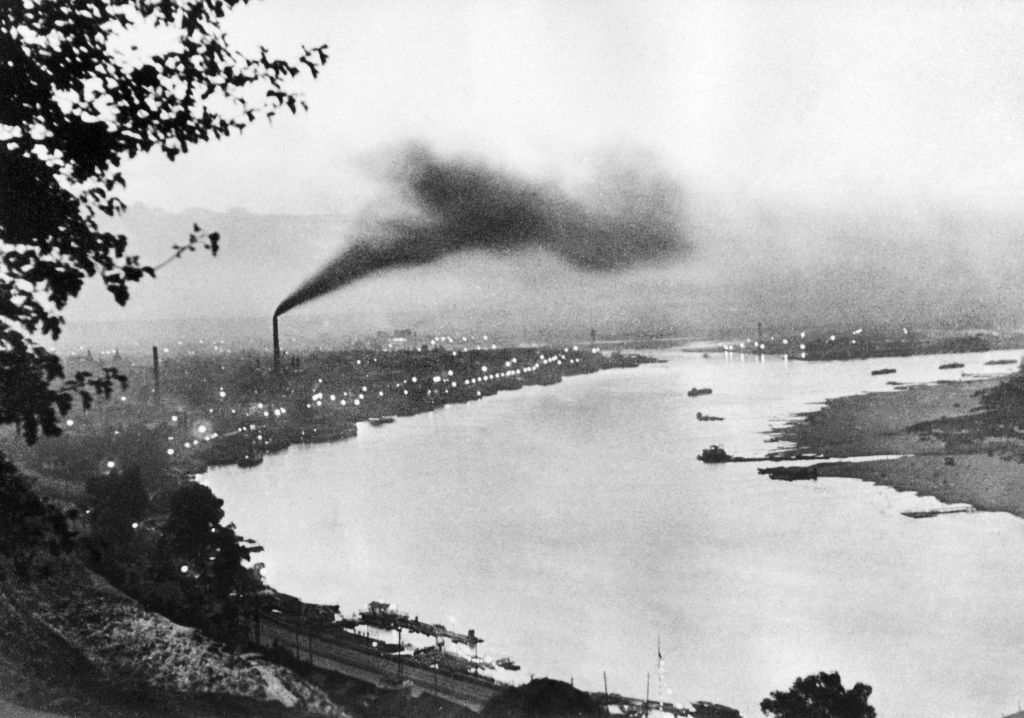

Nowadays, the Dnieper rapids are no longer visible. They were drowned by the rising waters of the artificial Dnieper Reservoir, which came into being in 1932 in consequence of Stalin’s Five Year Plans and the construction of the colossal hydroelectric dam at Dniepropetrovsk (now called Dnipro).

Nonetheless, the Dnieper remains the most prominent physical feature in Ukraine’s broad steppes, and it effectively divides the country’s 600,000 km2 into centre, East and West. Nearly 2,000 miles in length, it rises near the source of the Western Dvina – which gave the Vikings access from the Baltics – and flows south through several climatic zones to the sea facing Turkey. In places, it flows through deep gorges. Elsewhere it can be ten, 20, or even 30 miles wide. It is not a barrier which the Russian army is ever going to cross with ease.

Putin and other Russian nationalists are deluded to think that a large and natural pro-Russian constituency awaits them in Ukraine

Central Ukraine is taken up by the Dnieper Valley, dominated for a millennium by the city of Kyiv, which lies some 360 miles from the sea. Having spent over three modern centuries under Russian rule, Kyiv’s population is mainly Russian speaking (like President Zelensky) though in the past it housed lots of Poles, Jews and Ukrainian speakers from the countryside. Politically, the key fact is that in the referendum of 1991, 90 per cent of Kyiv’s inhabitants, whatever their linguistic affiliations, voted freely for Ukrainian independence. Geographically, though the city’s ancient districts are built on the river’s high banks, the valley bottom is filled with a mass of lakes, ponds, marshes and waterways, which earlier this year thwarted the Russian army’s offensive.

Eastern Ukraine – on the Dnieper’s left bank – naturally forms the region where Russian-speakers are most numerous. The Russian border lies some 200 miles east of Kyiv. Yet this is not aboriginal Russian territory. In 1709, when the fateful Battle of Poltava took place, the battle site still lay in the Kingdom of Poland. Charles XII, King of Sweden, had already conquered Poland before heading out to confront the Russian army under Putin’s victorious hero, Peter the Great. At the time, the local population would have been largely Ruthenian, and it was only in later times, especially through industrialisation, that linguistic Russification took place.

The most fateful day in Ukraine’s industrial history occurred in 1869, when a Welsh mining engineer from Merthyr Tydfil, John Hughes, bought an empty plot of land in the Donetsk river coal basin and built the Russian Empire’s largest ironworks. The town of Yuzovka – i.e. Hughesville – attracted hordes of Russian migrant workers and built a vibrant proletarian, ‘workers’ culture, not dissimilar to that of Hughes’s native South Wales. It was nationalised during the Bolshevik revolution, re-named ‘Stalino’ in 1924, and eventually emerged as Donetsk in 1961. It was the most Bolshevik-friendly and ‘Sovietophile’ city in the whole USSR, and after the Soviet collapse became a political base for the pro-Russian boss and Ukrainian president, Viktor Yanukovych.

The vast stretch of land which makes up western Ukraine has to be divided into at least three sub-regions, each with different historical and geographical connections. Most of it once belonged to Poland, and was an area in which Europe’s largest Jewish community had been housed for centuries (85 per cent of Jews in the world today can trace their roots to Poland-Lithuania). After the Russian conquest of 1793, it provided the largest slice of Russia’s Pale of Jewish Settlement, beyond which Jews were not permitted or supposed to live. But it also provided the land for the huge Tsarist colony of ‘New Russia’, whose ‘black earth’ was to support the most fertile grain-growing land in Europe. During the colony’s organisation, Prince Potemkin sailed down the Dnieper with the Empress Catherine, entertaining and deceiving her with the songs and dances of his garlanded soldiers dressed up as happy villagers. Russian landowners moved in. The Ukrainian peasants remained serfs until 1864. But ‘Europe’s bread basket’ boomed.

In Ukraine’s West, the south-west corner – connected to the interior by another great river, the Dniester – abuts the Balkans. Romania looms along the coast, landlocked Moldova some two hours’ ride inland. The breakaway strip of Transnistria, controlled by the remnants of a stranded Soviet army, is hoping for a rescue from Putin’s men. Yet the nearby port city of Odessa, founded in 1801 to service the products of New Russia, is dominant.

Throughout the nineteenth century, as described in Neal Ascherson’s wonderful book. Black Sea, it was a vibrant, multinational, multicultural metropolis, where Poles, Jews from the Pale, Greeks, Romanians, Ukrainians and Russians met and mingled.

Ukraine’s mountainous far West, in Carpatho-Ukraine, was an area where the borders of Hungary, Czechoslovakia and Poland once converged. It now boasts several popular ski-resorts and an exit route for refugees.

The present north-west region of Ukraine has been most heavily influenced by Polish rule and civilisation, which lasted there for more centuries than Russia’s did; it is regarded as the bastion of modern Ukrainian nationalism. The city of Lviv, formerly Lwów, was a predominantly Polish and Jewish metropolis from 1349 to the deportations and ‘repatriations’ of 1945-6. Once the capital of Austro-Hungarian Galicia, it was briefly in 1919 the centre of a ‘West Ukrainian Republic’ and the scene of Polish-Ukrainian conflicts, from which Russia was the sole beneficiary.

Ukraine’s south consists entirely of the Crimean peninsula and of the coastlands that face it. Annexed by stealth and subterfuge in 1783, as again in 2014, it is no more Russian in origin than anywhere else. Crimea was the homeland of the Muslim Crimean Tatars, who were dispossessed by Catherine the Great and deported en masse by Stalin. It was duly transformed into a militarised district supporting the naval base of Sevastopol, home to Russia’s Black Sea fleet, which, during the Crimean War of 1853-6 became the target for allied intervention. One hundred and sixty years on, the imported Russian military still forms the core of the peninsula’s population, like the Americans of Diego Garcia. The Ukrainians never held a close connection to Crimea or to its adjacent coastlands until 1954, when, to pacify anti-Russian rumbling and to celebrate the tercentenary of Khmielnytski’s Rising, Soviet Ukraine was handed the peninsula as a pre-wrapped gift. Today, Ukrainians think of it as theirs.

It is difficult to imagine, short of reviving Stalin’s methods, how any of these historical faits accomplis can be reversed.

Yet Putin and other Russian nationalists (like the recently newsworthy Alexander Dugin) have been deluding themselves by thinking that a large and natural pro-Russian constituency awaits them in Ukraine. Several groups of Moscowphiles do indeed control pockets including the Donbass, Crimea or Transnistria. But they are overshadowed ten times over by far larger regions and districts, which Putin cannot possibly occupy and whose inhabitants, whether they speak Russian or not, see no joy in Moscow’s embrace. Prior to 2014, a substantial element among Ukraine’s citizens wavered in their identity. But Putin’s savage war has put an end to their wavering. Just as the invasion has resulted in further extensions to Nato, so it has equally put granite into Ukrainian resolve, which in the long run will be a vital factor in the outcome. Putin would not be the first adventurer whose canoe came to grief on the rapids.

Comments