In Michel Houellebecq’s satirical novel Soumission, the French elite submits to Islamic rule rather than accept a National Front government. Nine years after its publication, submission seems more imminent on this side of the English Channel.

My American friends are surprised to learn there’s no equivalent to the First Amendment in Britain. They have forgotten a free press was one of the things their ancestors rebelled to establish in the US. Free speech is a much more recent thing in the UK. If it was born in the 1960s, it seems to be dying in the 2020s.

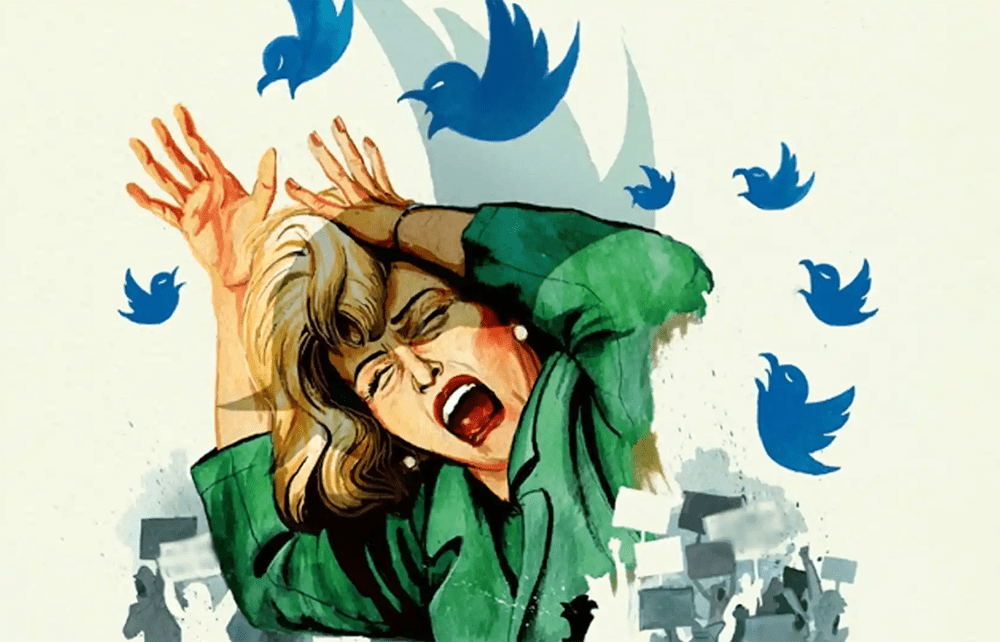

If free speech in the UK was born in the 1960s, it seems to be dying in the 2020s

After the recent riots, people were given prison sentences for posting words and images on social media. In some cases, the illegal incitement to violence was obvious. Julie Sweeney, 53, got a 15-month sentence for a Facebook comment: ‘Blow the mosque up with the adults in it.’ Lee Dunn, 51, on the other hand, got eight weeks for sharing three images of Asian-looking men with captions such as ‘Coming to a town near you’.

As these sentences were delivered, the government announced its intention to axe the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act. Education Secretary Bridget Phillipson said the act, which requires universities and students’ unions to protect free speech and academic freedom, would place too much of a burden on universities and expose them to costly legal action. But there’s been speculation the real motive for ditching it is to avoid antagonising China, a country noted for the number of students it sends to the UK, not for its commitment to free speech.

When I came to the West in 1992, free speech seemed a settled issue. From defamation to fraud, perjury to libel, insult to incitement, the legal limits were largely decided.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in