Beirut

On the highway into Beirut the other day, we drove past a petrol queue that was more than two miles long. On and on it went, the drivers sweating and swearing in brutal heat. Some had run out of fuel while they waited, having to push their cars when the queue inched forwards. There were people on laptops working from their cars during the day-long wait. Petrol queues are an everyday fact of life in Lebanon, but this was something else. Seeing that I was a foreigner, a frustrated driver gestured at the long line ahead of him and shouted: ‘Lebanon!’ He was summing up the fury and disgust felt by the Lebanese at what has happened to their country.

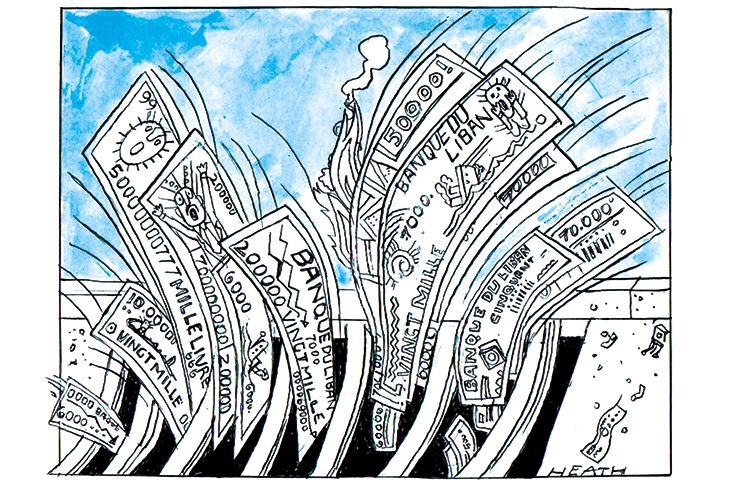

The fuel crisis is one sign of an economic disaster that has seen Lebanon’s currency, the lira, lose 95 per cent of its value over the past 18 months. Mostly, that means rising prices. But sometimes — thanks to the unintended consequences of government interference in the market — it means falling real prices and shortages of commodities such as fuel. In one petrol line was Hani Chiah, a 60-year-old man driving a gleaming black SUV. The car wasn’t his. He had been employed as a site manager on big construction projects, earning good money. But the work had dried up and now he was reduced to chauffeuring around one of the Lebanese super-rich who, presumably, still had access to dollars. Hani had been there since 6.30 a.m., waiting for four hours so far. He recited the familiar lament of the Lebanese middle class: ‘We used to go out to have fun. We used to buy clothes to look good. Now, we don’t do any of the things that bring joy to life. Now, we just try to survive.’ He was scared for his children and grandchildren.

The government is clinging to the fiction that the currency is worth many times its real value

The petrol shortage is a good place to start in trying to understand the sheer madness of what happens to a country when you can’t trust the money any more. As I write, a dollar buys you a little more than 22,000 Lebanese lira on the black market; almost 15 times the official rate of 1,500. The government still uses the official rate in calculating some prices, which has important consequences. Filling up my car used to cost about 60,000 lira, or $40. It’s now around 120,000 lira because there are price controls for fuel — but those lira have cost me around five bucks. If you don’t ration by price, you ration by queuing. Result: chaos. My tank of fuel still costs $40 in the real world so the government has to subsidise imports. But the government is — unsurprisingly — running out of hard currency, so less and less of anything with a subsidy is coming into the country. More petrol stations shut. The queues grow longer.

Medicines are another commodity where the government clings to the fiction that the currency is worth many times its real value. At a pharmacy in a Christian neighbourhood of Beirut, the owner, a middle-aged woman in a white coat, was turning away a stream of dissatisfied would-be customers. ‘No,’ she said to a lady gripping a list of medicines for her diabetic husband. ‘No,’ she said to every item on a longer list from a second woman. The answer was ‘No’ for everyone except for a man who had come in for throat lozenges. They were turning away people who would certainly die without what was written on their prescriptions, she and her colleagues said. People would weep, beg, shout, but there was nothing to be done. A young man in a white coat who turned out to be a pharmacy student said he planned to flee Lebanon. Perhaps 70 of the 75 people in his year at college would do the same. ‘I cannot live in this kind of country.’

Medicines and fuel are also short because they are being smuggled out of Lebanon by criminal gangs. Local TV reported on how a heart medicine now impossible to find here had turned up in a market in Congo, still with the labels from a Lebanese pharmacy. Cancer medicines show the huge profits to be made. Our children’s nanny has breast cancer and in normal times her treatment would be impossibly expensive: the drugs she needs cost $300,000 from their American manufacturers. We managed to buy them for about $20,000. The price was calculated at 1,500 Lebanese lira to the dollar, but we had bought our lira from Mohammed the money dealer at more than ten times that rate. I tipped out more than 100 million lira on to the desk of the hospital administrator, one part of the bill for treatment, temporarily feeling rich. Our nanny is one of the very few people to benefit from Lebanon’s economic collapse (and even then, her medicines may not be available the next time we try to buy them).

Most Lebanese have seen their salaries fall further and further behind prices that seem to rise almost every day. A report by the UN children’s agency Unicef says 30 per cent of Lebanese children have to skip meals and go to bed hungry, while more than three quarters of households don’t have enough food. In Beirut, little knots of child beggars — stick thin and dressed in rags — rap on car windows at traffic lights.

When things are this bad, you start to wonder how long the institutions of the state, perhaps the state itself, can survive. For the past year, the Lebanese army has not put any meat in meals for soldiers on active duty. The army chief of staff, General Joseph Aoun, is begging foreign governments to send food so that, as he said in a speech, ‘the army can stay on its feet’. Aid for the army is coming from, among others, Egypt, a deeply humbling thing for Lebanese used to seeing Egyptians pumping their gas and collecting their rubbish. But the army is so desperate for money that it has started flogging rides on its helicopters to any tourist with $150 to spare. That sum, converted into lira at the unofficial market rate, is twice the monthly salary for ordinary soldiers.

Lebanon got this way partly because the central bank kept the currency hugely overvalued. This worked because millions of Lebanese abroad kept sending dollars home to deposit in banks here. Some of those dollars went to the central bank, which used them to prop up the lira in the currency markets. The bankers got bonuses in the tens of millions of dollars; the depositors got suspiciously high interest rates, financed by the central bank’s printing presses.

It was all fine until the supply of dollars from abroad began to drop off. This happened slowly at first, because of poor global economic conditions, but later rapidly, because of the pandemic and then an explosion at the port of Beirut that devastated large parts of the capital. The banks got so desperate there are stories of rich expats being called up and offered a 25 per cent annual return if they would bring their money home. Inevitably, this Ponzi scheme collapsed. The banks pulled down their shutters, furious depositors banging on the doors.

Eighteen months on from the economic crash, no one has been held accountable, no one has stepped down: not the central bank governor, not the heads of individual banks, not the politicians. All Lebanese are to some extent complicit in this disaster: the overvalued lira was universally popular; it made everyone feel richer than they were, able to afford German cars and Ethiopian maids. But the Lebanese government is too paralysed with fear to do what needs to be done now. A senior banker told me the political class would spend the last dollar in the central bank and all the gold there as well before ending subsidies: ‘They know they will be killed if they don’t.’

Trouble in Lebanon has a way of quickly becoming sectarian. Already there are reports of militias guarding petrol stations in areas they control. Whether there will be another civil war here is a matter of the country’s tragic history and current politics. But here are universal lessons for western economies busily printing money to deal with the economic effects of the pandemic. This country shows what happens when governments abandon the boring but vital business of ensuring sound money. Lebanon is a warning to us all.

Comments