It happened by accident. In 1829 the naturalist Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward was trying to hatch a moth pupa. He placed it in a sealed glass container, along with some soil and dried leaves, and set it aside. Sometime later he was surprised to find that a fern and some grass had taken root in the soil, despite having no water. As Sathnam Sanghera writes in Empireworld, the discovery ‘revolutionised the logistics of international plant transportation’. Suddenly there was a means of securely transporting seeds and seedlings across vast distances.

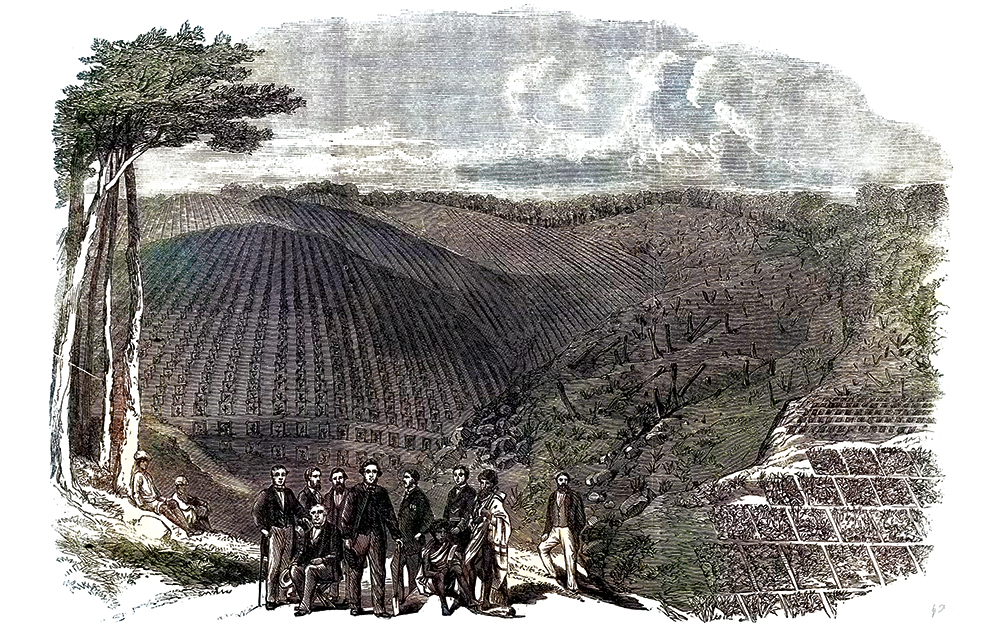

Empireworld is a sequel to Sanghera’s wildly successful Empireland. Where the latter examined the legacies of empire in Britain, this book seeks to apply that template to the world. What, then, do glass containers have to tell us about global imperialism? One result of Ward’s discovery was that Britain was able to transplant the cinchona tree, native to South America, to its colonies worldwide. Cinchona bark contains quinine, an alkaloid which prevents malarial fever; and it was quinine, together with the steamship and the Maxim gun, Sanghera writes, that enabled the late 19th-century conquest of Africa by European powers. Before that, much of the continent was simply too deadly. A European arriving in Mali had a life expectancy of four months.

Sanghera finds British imperialists to be the fons et origo of all today’s unrest in Kashmir, Iraq and Myanmar

But the new global live-plant trade also spread pestilence: some 90 per cent of invertebrate pests in Britain today arrived that way. Imported diseases ravaged imperial plantings; one fungus alone destroyed £2 million’s worth of coffee plants in Ceylon in 1869. Ward’s discovery then, was both a triumph and a disaster. As such it is a useful metaphor for Sanghera’s central argument, which is that trying to balance out the impacts of British imperialism by weighing ‘good’ against ‘bad’ is futile.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in