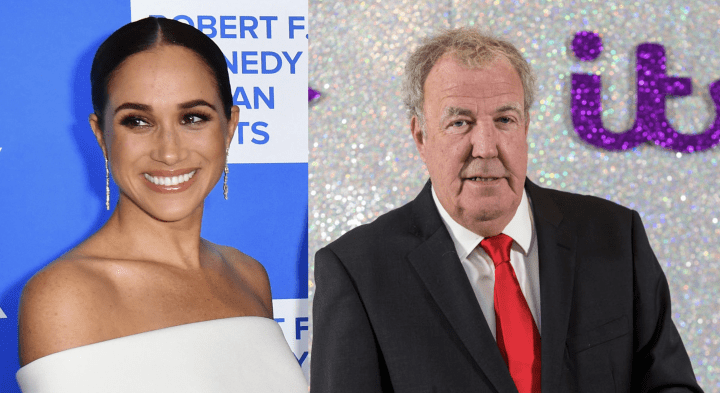

At 10 p.m. on Friday night, the BBC sent out a ‘breaking news’ notification informing millions that a joke made by Jeremy Clarkson about Meghan Markle has been deemed sexist by Ipso, the press regulator. That such attention was given to a few sentences published on p17 in a months-old article is odd, but the BBC had cottoned on to an important point: the battle for press freedom had just suffered a major setback. Hacked Off, an outfit campaigning for state regulation of the press, reacted with typical illiteracy, announcing: ‘Ipso finally upholed [sic] sexism complaint’ marking ‘the first time in Ipso’s history that it upheld a complaint about sexism’. It is right to say that a bridge has been crossed, a defence of press freedom trampled upon. The activists have finally found a way through.

By upholding the Clarkson complaint, Ipso has torn up the previous protection expressed in its Editors’ Code: that opinion is not regulated. You’re not supposed to be able to complain on someone else’s behalf unless you have found a factual error: this a clause intended to stop Ipso being manipulated by activist groups. ‘Complaints can only be taken forward from the party directly affected’, ran the old rules. Had Meghan complained? If not, nothing to investigate. Ipso checks accuracy and protects individuals from press misbehaviour – but it was not set up as a thought police. It doesn’t judge taste.

The Clarkson ruling changes the rules. Activists can now complain on someone else’s behalf. Ipso, it seems, is now in the business of deciding if columns are sexist. And who do we find leading the charge in this new regime? Harriet Harman, the incoming chair of the Fawcett Society who is doing a lap of honour about the ruling. Fawcett lodged the complaint and in upholding it Ipso has, in effect, given Harman an editor’s pen. One she is unlikely to hold back in using. If the ruling is allowed to stand (a judicial review is perhaps the only tool left to strike it down) then it has chilling new implications for every Ipso-regulated publication, including The Spectator. The Hacked Off “upholed” statement contained quotes from the Fawcett Society, raising the prospect of their collusion in this affair.

What follows is complex, but it matters. The contours of free speech are decided by such technicalities.

Ipso and free speech

Until now, a joke by Clarkson would have been a matter between the newspaper and its readers. But the digital age has brought informal pressure, where screen-grabs allow a publication’s non-readers to vent outrage (the main commodity pushed by Twitter) and demand punishment or censorship. Jokes and satire are targeted the most, often presented as hate crimes. A trivial verbal flourish can, in this way, be treated like a heinous assault: one to be punished with the firing of the writer. Many publishers panic. From Iain Macwhirter to Kevin Myers, the mob are used to publications giving them the scalps they demand.

Ipso was designed to withstand the pressure of online mobs. It had, until now, made this clear: if a Clarkson joke offends you, or if you don’t like what the Daily Mail said about Angela Rayner or its ‘Legs-it’ cover featuring Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon, don’t waste your time complaining to Ipso. It only takes complaints from those people referred to by the writer. It’s there to protect individuals, not to do the bidding of activists. This was an iron rule, repeated in Ipso verdicts time and time again.

But Clarkson’s joke about Meghan whipped up a Category-A Twitterstorm with 60 MPs expressing their outrage. Until now, their opinion did not count for anything. In Britain, politicians have no writ over the press – which is why it’s so worrying to see Harman claim victory over the press, in her guise as chair of an activist group.

Let’s go back to what Clarkson said. He had watched the Meghan Markle Netflix documentary. Safe to say he was not a big fan.

I hate her. Not like I hate Nicola Sturgeon or Rose West. I hate her on a cellular level. At night, I’m unable to sleep as I lie there, grinding my teeth and dreaming of the day when she is made to parade naked through the streets of every town in Britain while the crowds chant, ‘Shame!’ and throw lumps of excrement at her.

Any Game of Thrones fan will have got the reference and those unfamiliar would have got the idea. Clarkson had a few more things to say, like that Markle used her feminine wiles to make her husband woke, etc. Were his jokes risqué? Absolutely. Funny? Sexist? Over the line? Here’s the point: in a free press, no outside organisation can draw that line. It’s between readers and the writers: no one else. The law stipulates what is illegal, and press regulators insist upon factual accuracy. But opinions? They are not regulated in this country and have not been for 300 years. This is a fundamental point upon which free speech and press freedom depend.

The Sun did decide it was a mistake to publish. It apologised (as did Clarkson) and the piece has been purged from cyberspace. But as the Sun is now finding out, apologies only intensify a Twitterstorm: some 25,000 emails ended up being sent to Ipso about Clarkson, the most complaints ever received by the regulator. This figure is of course dwarfed by the 700,000-strong readership of the Sun, but I doubt the latter wrote to Ipso. The asymmetry worked and Ipso crumbled.

In deeming Clarkson sexist, Ipso has – for the first time – imposed on newspaper columnists a line drawn by others (usually those who hate the publication they’re complaining about). ‘A big step forward,’ boasts Harman. It certainly is. An independent press regulator, which is supposed to defend the press and readers against Twitterstorms and political interference, has just succumbed to both. How? Why?

The Ipso rules so far

The charter that governs Ipso’s relationship with its member publications makes clear that complaints from activists should be rejected on principle. ‘Our regulations do not allow us to take forward complaints about issues other than accuracy from third parties,’ it said. Let’s take two examples.

Twitter went berserk when the Mail on Sunday wrote about what it described as Angela Rayner’s Basic Instinct leg-crossing tactics in parliament. Some 6,000 emailed complaints to Ipso, which rejected them all saying it could not act unless Rayner herself complained about the analogy. (And no wonder: it later emerged that she was the source.)

When Katie Hopkins referred to migrants as ‘cockroaches’ it was a disgusting comment that, in my view, should never have been printed. But Ipso was firm. It is not in the business of drawing the line on language, taste or opinion. A hate crime? Then let the police deal with it. ‘While we noted the general concern that the column was discriminatory towards migrants,’ it explained to one complainant, its rules are ‘designed to protect identified individuals mentioned by the press against discrimination, and do not apply to groups or categories of people.’ In a liberal society, idiots are not banned or censored. Anyone should be free to spout shock-jock drivel and then slide towards deserved obscurity, as Hopkins has now done.

The Ipso loophole used to nail Clarkson

In certain niche cases, third-party complaints are allowed. An article denouncing all chiropractors as quacks, for example, could be subject to a complaint by the British Chiropractor Association. When the Daily Express published ‘39 of the World’s Worst Mugshots’, Ipso did recognise a complaint from a group dedicated to the victims of facial disfigurement. But these aggrieved groups were defined as niche – not as wide as a nationality, race, religion or gender. To do the latter would open the floodgates to activists offering their own definition of bigotry and force Ipso into the business of regulating opinion.

Let’s look at Ipso’s lengthy Clarkson verdict. In effect, it’s a manifesto of the new rules under which the Ipso-regulated press must now operate:

- ‘Ipso’s Complaints Committee decided that the complainants represented groups of people who had been affected by the alleged breach of the Code.’ Absurdly, the obscure Fawcett Society is seen as ‘representative group’ for womankind. A dangerous new principle. On this basis, any outfit can now claim to speak for anyone.

- ‘That the alleged breach was significant.’ In what way was a joke midway through a p17 column deemed ‘significant’? Because of the Twitterstorm. So here’s the second new Ipso principle: Twitter now decides if things are significant. It is a game of how many emails are sent: so campaigners can, in this way, bend the regulator.

- ‘There was a substantial public interest in Ipso considering the complaint’ – a reference, it seems, to the 60 MPs who were baying for Clarkson’s punishment. So now we see a mechanism for politicians to call the regulatory shots.

So this ruling is every bit as momentous as Hacked Off suggests: a clear violation of Ipso’s founding charter and (to this editor, anyway) a breach of contract with its member publications. The Sun pointed this out and fought every step of the way. Its failure suggests that Ipso’s word (and mutation) is final. This has fateful consequences for every publication Ipso regulates, The Spectator included.

The Spectator and Ipso

So far we have found Ipso to be a robust regulator and, generally, a force for good. The Spectator takes accuracy very seriously and the Ipso code offers helpful clarity for readers and writers alike. For example, a columnist may file a copy referring to something they heard on the radio. We then have someone find the programme, listen back and ensure that it’s accurately characterised in the article. Columnists are not researchers. That work is done by us, in 22 Old Queen Street. It’s exhausting and out small team has three people devoted to this now: a big investment on our part. But even without Ipso I’d still, as editor, want that work done. If you read an article in The Spectator saying things happened in a certain way, then you can be sure that they did.

Ipso membership helps me, as editor. I may be asked: is this ‘red team’ operation of yours a bit expensive? Three of them, in team of barely two dozen staffers? Must we really pay someone to listen to an hour-long radio programme to ensure a columnists’s passing reference is accurate? I can say: yes, the column is controversial and liable to Ipso challenge. We need to protect our writers by ensuring that it would survive such a challenge. Our readers like to know the facts in The Spectator are one hundred percent reliable. We go to such lengths because we care. And when we go big-game hunting, we like to be on target.

But opinion? Taste? No code can judge that; one man’s truth is another’s apostasy. Ipso’s remit is clear on how it should have no remit in this field.

The [Ipso] Editors’ Code does not address issues of taste or offence. It is designed to deal with any possible conflicts between the right to freedom of expression and the rights of individuals, such as their right to privacy. Newspapers and magazines are free to publish what they think is appropriate so long as the rights of individuals – which are protected under the Code – are not infringed.

It’s important that against-the-grain voices are heard, rules challenged and fashionable views held up to ridicule. Since 1828, The Spectator has been an abattoir of sacred cows, allowing all kinds of jokes on topics that polite society would have regarded as out-of-bounds. We savaged the obsessions of late-Georgian society, holding the powerful up to ridicule and mocking fashionable deities. We were denounced as the ‘buggers’ bugle’ for coming out for the decriminalisation of homosexuality in the 1950s – then, that was apostasy. We almost went bust being the only UK publication to back the North against the slave-owning South in the American civil war: we were isolated, causing outrage but sometimes that’s good in a democracy. Today we have Rod Liddle, Lionel Shriver, Douglas Murray and many more puncturing contemporary pomposities, who often use humour and satire. How many of their conclusions will now be subject to activists’ censure?

Ipso has worked, as a press regulator, because its rules have been clear and its judgments logical and predictable. But if Ipso has lost its nerve and is suddenly taking its lead from activist groups, then it’s whole a new ball game. If Ipso’s judgement depends on how many emails of complaint it has received from our non-readers, or how upset Twitter is, then the self-regulatory system risks collapse. It’s far from clear to me that Ipso has the legal power to expand its remit in such a drastic way, in defiance of its contract with its members. A judicial review may be able to offer clarity on this point.

The Spectator will now seek clarity from Ipso about the implications of this judgment and whether they are now in the business of censoring opinion on behalf of Harman and her proxies. If so, we will respectfully disengage and I suspect other publications will not be far behind us. Some have suggested that this is a one-off: the Ipso’s rules are now applied in different ways depending on who is accused. If so, that’s just as bad.

This matters. Labour’s last manifesto committed the party to state regulation of the press. Keir Starmer could well go through with it. Especially if he ends up in coalition with the Liberal Democrats, whose deputy leader is a Hacked Off alumna. The Spectator has pledged to its readers that we will never sign up to state regulation, no matter what the consequences. The fight for press freedom may be starting again. If Ipso has fallen and now stands in violation of its own charter, its member publications will certainly have some thinking to do.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in