The hall was before me like a gigantic shell, packed with thousands and thousands of people. Even the arena was densely crowded. More than 5,600 tickets had been sold.

Cyril Bertram Mills started his circus career accompanying his father to European horse fairs in the 1920s. The two of them were soon familiar faces on the German circus scene, travelling between shows to recruit acts for London. The Munich Circus was a particular draw; but sometimes they hired out their circular wooden building to other local acts. The opening quote of this review comes from Adolf Hitler. Mills was at first dismissive of the Munich Nazi party leader, pointing out that hippos, monkeys and pigs ‘also received enthusiastic receptions in the same circus arena’. But the fact that Hitler was even on his radar, combined with the cover provided by his circus business, gave Mills a head start on intelligence gathering when the Nazis began to gain power.

The circus industry and the secret world of intelligence may appear to have little in common. As Christopher Andrew points out, one courts the spotlight while the other aims to avoid it. Yet it was circus work that enabled Mills to operate hidden in plain sight as he flew his de Havilland Hornet Moth between acts across Germany, at the same time gaining valuable aerial intelligence on the country’s illicit rearmament. The circus also gave Mills useful transferable skills. It trained him to keep his nerve, manage unusual characters and risks, and effectively deceive others by creating fantasies – the last a habit he kept up until his eighties.

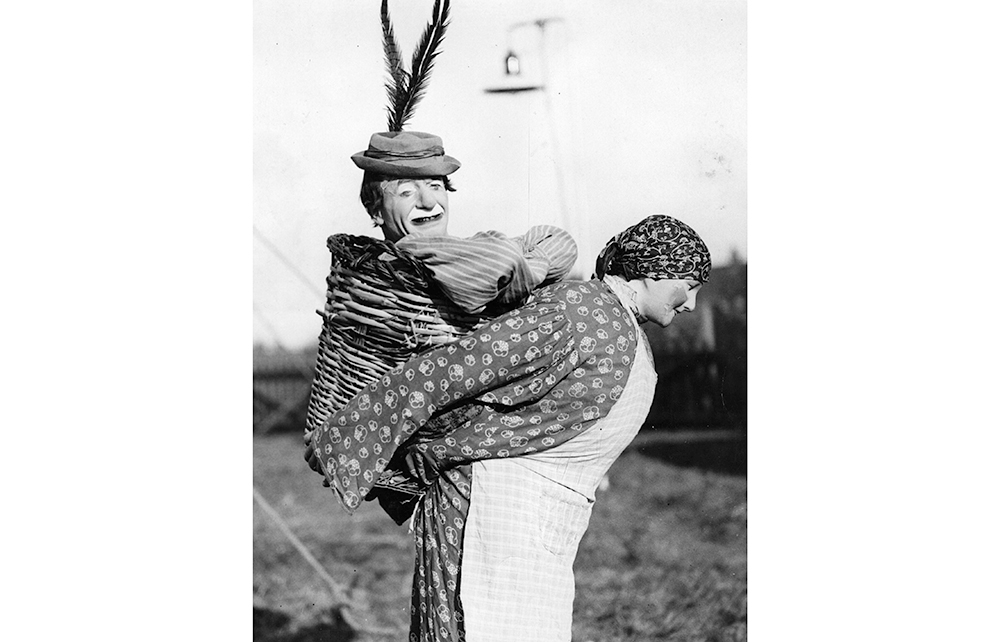

Andrew exploits this rich circus theme to the full. Hermann Göring raises lion cubs; Winston Churchill guffaws at clowns; and among those ‘possibly somewhat inspired by Mills’s circus career’ were the novelists Ian Fleming and John le Carré, the latter even christening his fictional secret service ‘the Circus’. There is also a wonderful cast of lesser-known characters from within both the entertainment and intelligence tents, including spies from many nations, an intelligence officer known for his tartan ‘passion pants’, and a Bordeaux dancer who named her crocodile ‘Churchill’ – later prompting the prime minister to approve the designation of a flame-throwing tank as the ‘Churchill Crocodile’.

The circus gave Mills useful skills, training him to keep his nerve and deceive others by creating fantasies

All of this keeps the pages turning nicely. Yet for an author who clearly admires the entertainment business, Andrew often seems to be writing against the grain. Indeed, the book’s opening gambit is so pedestrian (‘The chief influence on Cyril Bertram Mills’s early career was his father…’) that I found myself reading the first word of every line in case there was a hidden message. Andrew’s many books include the only authorised, much admired history of MI5. This has armed him with great contextual knowledge and plenty of interesting side stories to divert to, but there is surprisingly little here about Mills’s character, motivations or personal life. His second wife, Mimi, gets a few sentences; his first wife less than that. A file found after Mills’s death apparently included love letters, but none are quoted, meaning that Mills remains a rather enigmatic, if courageous, British patriot.

Prohibited from further German aerial recces after the outbreak of war, and too old to join the RAF, Mills was recruited by MI6 to work from the cells in Wormwood Scrubs, the service’s temporary wartime base. There he helped run the Double Cross system. He recruited Juan Pujol Garcia, one of Britain’s most successful wartime agents, to whom Mills gave the code name ‘Garbo’, in tribute to his star quality. Mills was Garbo’s first case officer but, having transferred to Canada before Garbo undertook his most valuable service, he narrowly missed the main action – as seemingly so often.

After the war and a little atomic secrets work, Mills moved his family to a mansion in Kensington Palace Gardens. The street was conveniently located opposite the Russian embassy, and as a result Mills played a major role facilitating, if not personally undertaking, surveillance operations that eventually led to a mass expulsion of Soviet intelligence personnel from London.

Mills was 89 when he died in 1991, having played significant roles in what was arguably the heyday of both the British circus and British intelligence. Claiming that he has never been given his due, Andrew turns the spotlight on Mills’s shadowy second career. But it seems rather to blanch the light, and the impresario himself remains an admirable silhouette against the spectacular stage sets of his life.

Comments