In January 1559 an Italian envoy wrote of Elizabeth I’s coronation that ‘they are preparing for [the ceremony] and work both day and night’. More than four and a half centuries later much the same could be said of the imminent investiture of Charles III – an event overshadowed, at the time of writing, by the uncertainty as to whether his publicity-shy younger son and wilting violet of a wife will be attending. But, as Ian Lloyd describes in The Throne, there have been many more dramatic build-ups to coronations, some culminating in injury or even death.

James I hired 500 soldiers as a personal bodyguard to shield him against ‘any tumults and disorder’

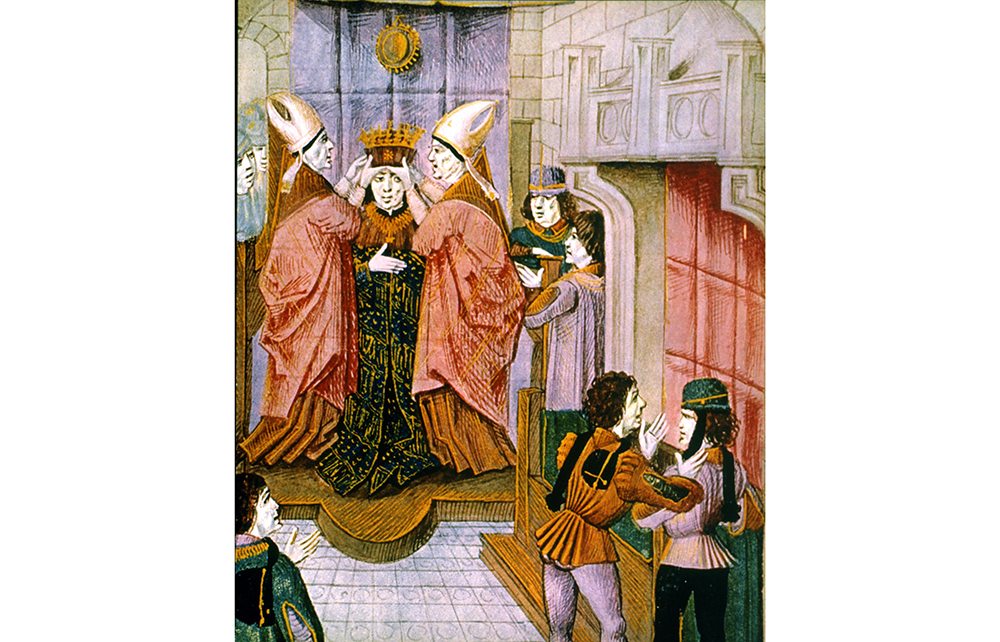

The scene is set in this brisk, gossipy history by William the Conqueror’s crowning, which took place at Westminster Abbey on Christmas Day, just two months after the Battle of Hastings – William’s hurry stemming from fear that his claim would be challenged. So tense was the atmosphere, the ceremony was interrupted by a guard torching nearby buildings after hearing noises of celebration, which he assumed to be a riot – meaning that the king’s consecration had to be completed amid looting and mass panic.

The first coronation for which any detailed records exist, Richard I’s on 3 September 1189, suffered from the bad omen of a bat fluttering around the throne – which was apparently borne out by the arrival of group of Jews bearing gifts for the new king. They were barred, and anti-Semitic riots erupted throughout the country. Centuries later, the same uneasiness prevailed at Mary Tudor’s coronation, her surly mood caused by fear of anti-Catholic rioting. In 1603, the paranoid James I hired 500 soldiers as a personal bodyguard to shield him against ‘any tumults and disorder’.

But not all monarchs regarded their investitures so grimly.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in