When Cicely Mary Barker’s Flower Fairies of the Spring was published in 1923, a post-first world war mass wishful belief in fairies was at its height in Britain. Just over two years previously, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, writing in the 1920 Christmas issue of the Strand Magazine, had stated that the ‘Cottingley Fairies’ (tiny winged figures visible in photographs taken near Bradford by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths) were almost certainly genuine and were clear evidence of the existence of psychic phenomena.

Barker remained unmarried, and lived a quiet life of flowers and innocence

The public – 21 years on from the birth of Peter Pan – were hungrier than ever for fairies: their innocence, their delicate beauty, and their hint of benign mischief. Barker, a young, unmarried illustrator living with her mother, and sister Dorothy, in Croydon, didn’t believe in fairies herself. She was an ardent Christian, and said that ‘fairies, and all about them, are “pretend”’. But she came up with the idea of tapping into the zeitgeist by creating books about fairies living at close quarters with the British flora of all four seasons.

She and Dorothy were galvanised by the urgent need to earn their living. Their father had died when Cicely was 17. Dorothy ran a kindergarten in the back room of their house, and Cicely used the pupils as models. The Flower Fairy books were an instant success, adored by everyone from Queen Mary downwards. They became part of the inner landscape of generations of 20th-century children (perhaps mainly girls), who found solace in the rosy-cheeked sweetness of the fairies, and usually avoided reading the sickly poems (also by Barker) that went with each one. (‘I’m the little white clover, kind and clean;/ Look at my threefold leaves, so green;/ Hark to the buzzing of hungry bees:/ “Give us your honey, clover, please!”’)

At the Watts Gallery Artists’ Village at Compton – a gem of old Surrey, consisting of a collection of arts and crafts buildings dedicated, chiefly, to celebrating the work of G.F. Watts, who lived there with his artist wife Mary – there’s an exhibition about Barker and her Flower Fairies. It’s small. Of the 80 or so Flower Fairy illustrations Barker did over the years, we only see six here: Agrimony, Lavender, White Bindweed, Elm Tree, White Clover, and Pink.

It’s a child-centric exhibition, and none the worse for that. In the first room, at child’s eye level, there are glimpses of Barker’s girlhood. Born in 1895, she suffered from epilepsy. A photograph of her on her ‘first day downstairs after three months of illness’, shows her sallow, with her nurse. She sold her first seaside illustrations as greetings cards aged 15. During the war, when the British were sending 800 million postcards a year, she drew ‘Picturesque Children of the Allies’ cards, honing her skills and depicting optimistic children gazing into the middle distance.

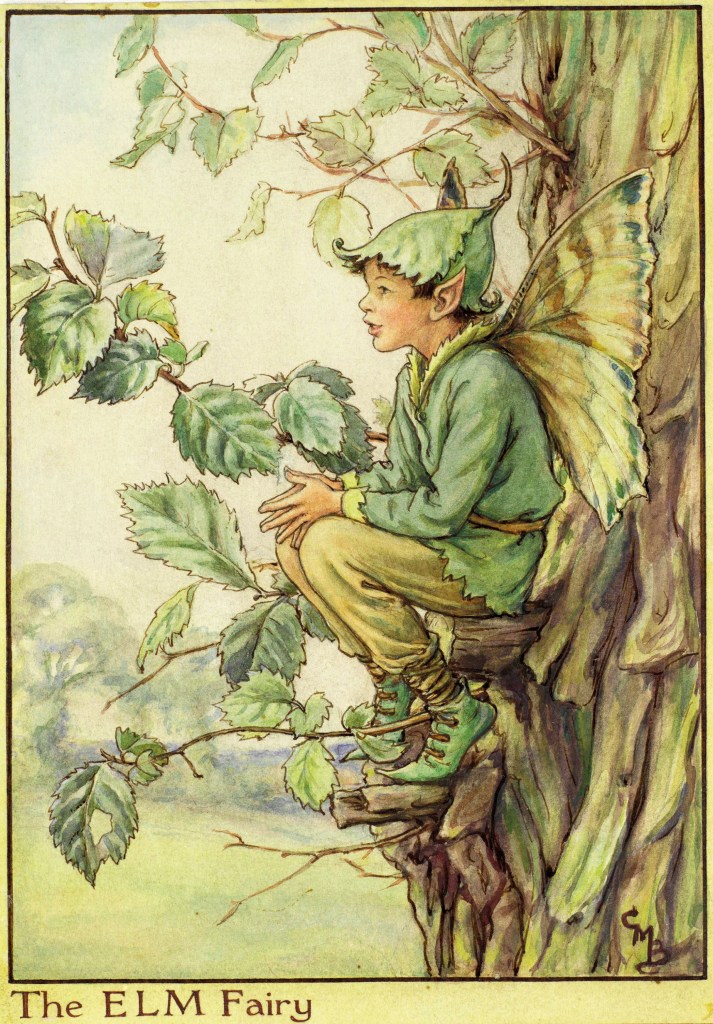

Then, you go downstairs to a small basement room to the Flower Fairies themselves. The small quantity is made up for by the thoughtful presentation of the process of each Flower Fairy’s creation: first, Barker’s study of the flower (Kew Gardens staff visited her with specimens; she took great pride in botanical accuracy); then a study of the child from Dorothy’s kindergarten, then a study for the illustration, and finally the finished illustration: human boy or girl transformed into a fairy with butterfly wings.

For the Elm Tree Fairy (see below), the boy model in the sketch is sitting on a flower pot wearing lace-up boots. By the time he becomes a Flower Fairy, not only has he acquired butterfly wings, but his ears have become pointed, his boots green and elfin with pointy toes, and he’s perching delicately on a branch with an elm-leaf hat on. The White Bindweed Fairy (female), similarly, has a bindweed-leaf hat and is kneeling weightlessly on leaves, gazing into a large white flower. Barker is good at fairy clothing, especially tights. The soldierly gait of the two Agrimony Fairies (both boys, one younger than the other) is made all the more charming by the smaller one’s tights being rumpled at the ankle as he marches along, holding his agrimony stalk aloft like a sword.

Barker remained unmarried, and lived a quiet life in her world of flowers and innocence. The final photograph of her is as an old lady, smiling in her doorway.

We were ushered from this exhibition straight into a studio which houses the full-scale gesso model for G.F. Watts’s statue ‘Physical Energy’(1880s-1904). The shock is extreme: from tiny fairies to the twice-life-size mass of tensed muscle of man and horse. It’s a great moment. Then, exiting past Watts’s pictures of a drowned Victorian woman, a dead heron, and a starving Irish family during the potato famine, you’re brought firmly back to reality.

Comments