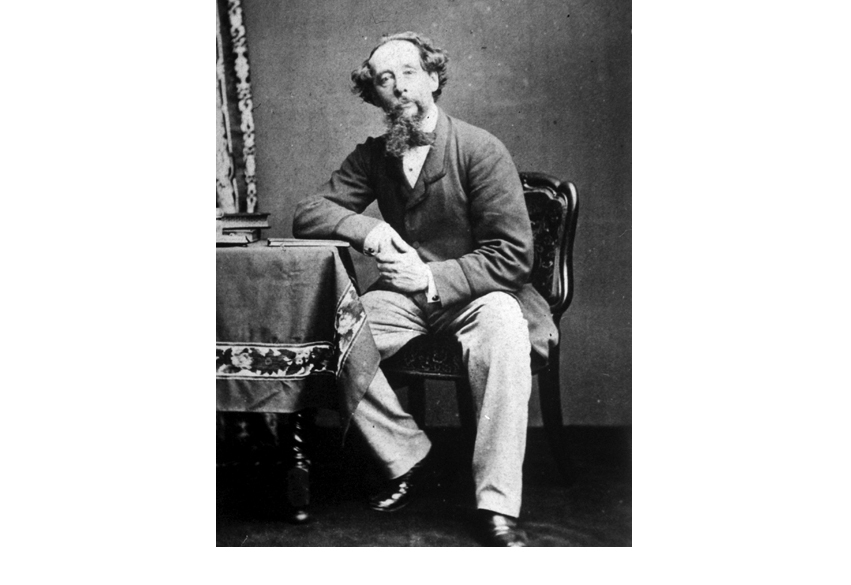

It is difficult to conceive of a writer more passionately loved by his audience than Dickens was. It went on for a very long time, too. We learn from the historian David Kynaston that, immediately after the second world war, Dickens was one of the five most borrowed authors from public libraries. My grandmother was probably a typical reader of Dickens: she left school at 14 before the first world war, yet had a cheap set of Dickens in the house (I think it was a promotional giveaway by the Daily Express at some point in the 1930s.) I have the set — the typeface and the acid paper nearly make your eyes and fingers bleed. And yet she read most of them a lot more than once: the copy of David Copperfield falls apart as you open it. A century after thousands of ordinary admirers filed past Dickens’s coffin in Westminster Abbey, ‘bringing’ (as Claire Tomalin says) ‘the heartfelt, useless notes they had written for him, and offerings of flowers that filled up and overflowed the grave’, many thousands of ordinary, not very educated readers still loved him and thought of him as their own. Undergraduates nowadays find him much more of a challenge. But 200 years after he was born, he still looks, to many, like the author of the five greatest novels in the English language, and perhaps even, too, what Tolstoy called him, the greatest novelist of the 19th century; a greatness not founded in cold esteem, but passionate adoration. He still looks like what one of his contemporaries called him, ‘the brilliance in the room’.

Dickens has been much biographied, from his friend Forster’s excellent account onwards. There is the mythology, of course — the blacking factory, the early death of Maria Beadnell, the versions of his parents in his novels, the adult purchase of the boyhood dream of Gad’s Hill, the railway crash which almost killed Dickens and destroyed the manuscript of Our Mutual Friend, and the public readings which really did kill him.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in