‘I want big things to do and vast spaces,’ Edward Burne-Jones wrote to his wife Georgiana in the 1870s. ‘And for common people to see them and say, “Oh! — only Oh!”’ That, however, was only the first part of my own reaction to the exhibition at Tate Britain of Burne-Jones’s works. Perhaps I’ve got a blind spot when it comes to B-J, but time and again I found myself thinking, ‘Oh no!’

Nonetheless, this comprehensive display and the accompanying catalogue give plenty of clues as to where he went wrong. Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones (1833–98) followed an extremely unusual career path. He was the son of a struggling framer and gilder from Birmingham named Jones (he added ‘Burne’ much later to avoid ‘annihilation’ among the horde of Joneses). A clever lad, he went from King Edward’s School to Oxford, where he met his lifelong friend William Morris.

Burne-Jones did not go to art school, nor initially did he show much talent for drawing. In her catalogue essay Elizabeth Prettejohn writes approvingly that ‘in his intellectual habits’ he was more like ‘a conceptual artist of today’. In other words, he was an intellectual, driven by ideas, rather than a practitioner of the brush, fascinated, as the late Gillian Ayres put it, by ‘what paint can do’. But even those concepts of his were remarkably nebulous.

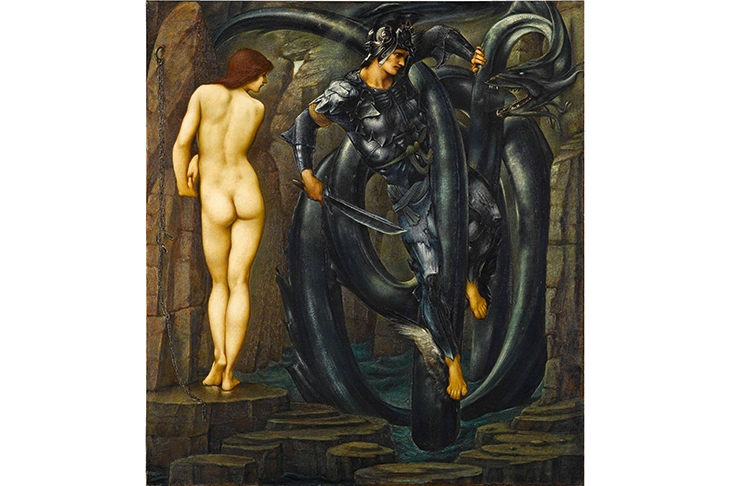

Burne-Jones wanted his pictures to be ‘a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was’. The location of this he described as ‘a land that no one can define or remember, only desire’. These are pictures of nowhere, which may be why figures don’t pay much attention to what’s going on.

Sometimes Burne-Jones depicted striking events such as the slaying of dragons.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in