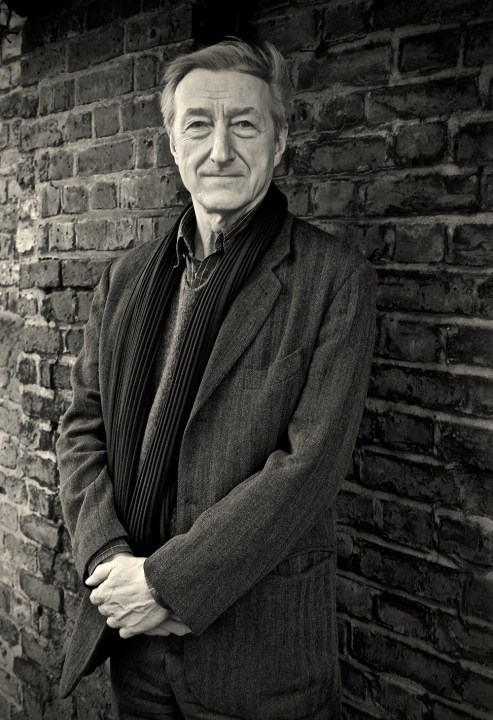

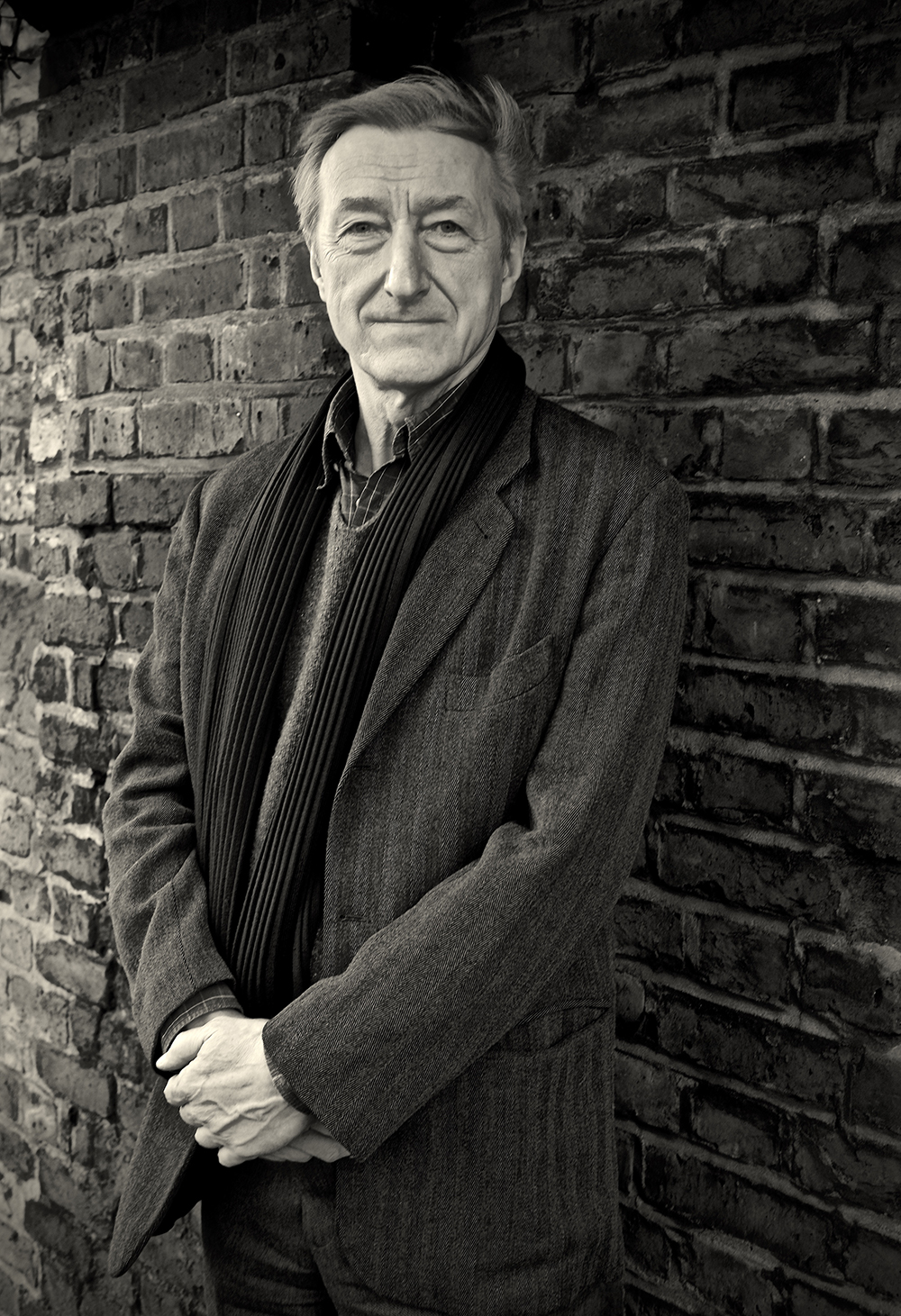

Not long into this essay I found myself wondering if it would have been published if the author were not Julian Barnes. I also wondered: would I have guessed the author’s identity if it had been withheld from me?

Actually, it’s really five little essays, whose subjects are ‘Memories’, ‘Words’, ‘Politics’, ‘Books’, and ‘Age and Time’. Here is a sample from the first section:

We change our minds about many things, from matters of mere taste – the colours we prefer, the clothes we wear – to aesthetic matters – the music, the books we like – to adherence to social groups – the football team or political party we support – to the highest verities – the person we love, the God we revere, the significance or insignificance of our place in the seemingly empty or mysteriously full universe.

Indeed, indeed (although I have not yet met anyone who has changed their allegiance to a football team. It’s kind of the point of supporting one).

The book is like this all the way through: an even tone, as that of the thoughtful vicar delivering an uncontroversial sermon in a venerable church somewhere in the Home Counties. As with such occasions, the mind wanders; one is intermittently brought back to either agree with a particular point or disagree with another; one surreptitiously looks at one’s watch and wonders when it will be over, or what’s for lunch. ‘Gradually,’ Barnes writes, ‘I have come to change my mind about the very nature of memory itself.’ (It is not to be relied on, basically.)

Here are the opening lines of ‘Words’:

I’ve spent my life with words, writing them and reading them. I believe deeply in words, in their ability to represent thought, define truth and create beauty. I’m equally aware that words are constantly used for the opposite purposes: to obfuscate truth, misrepresent thought, lie, slander and provoke hatred.

How true, how true. Barnes bemoans the loss of the ancient meaning of ‘decimate’, and points out that ‘disinterested’ used to mean ‘uninterested’, and vice versa. ‘There is no use indicting words,’ he writes, ‘they are no shoddier than what they peddle.’ Oh wait, no, he didn’t say that. That was Beckett. Barnes wouldn’t say anything like that.

When we get to ‘Politics’ we learn that Barnes has, over time, voted for each of the three main political parties, not so much because he has changed, but because they have. I now think of the Vicar of Bray, ungenerously. Barnes has an imaginary country in his head which he calls ‘Barnes’s Benign Republic’. In this utopia, there is public ownership of ‘all forms of mass transport and all forms of power supply – gas, electric, nuclear, wind, solar’.

I now think not so much of the clergyman addressing the flock as the earnest and articulate sixth-former shoving in a few extra words wherever he can to fill space but without making it look too obvious. He doesn’t specify what he means by ‘all forms of mass transport’, though. Are coaches included? Aeroplanes? I presume he just means trains, but I could be wrong. He also suggests a 50-year ban on any Old Etonian running the country – this amused me – and ‘massive investment in the National Health Service on both moral and economic grounds’.

His call for unilateral nuclear disarmament is no more or less than one would expect, although it made me wonder when he wrote this. Before Trump became president of the US, or before Putin invaded Ukraine? The world is on fire, but in his republic there will be a referendum on the monarchy’s existence (he expects it to survive) and increased rights of access for ramblers. As for the chapter on ‘Books’, we mainly learn that he used not to like E.M. Forster but now he does.

I think I would have worked out in the end that Barnes was the author, providing I’d been given a hint that he was a major British writer. Who else could it have been? As for the other question I posed at the beginning of this review, I leave that one hanging in the air.

Comments