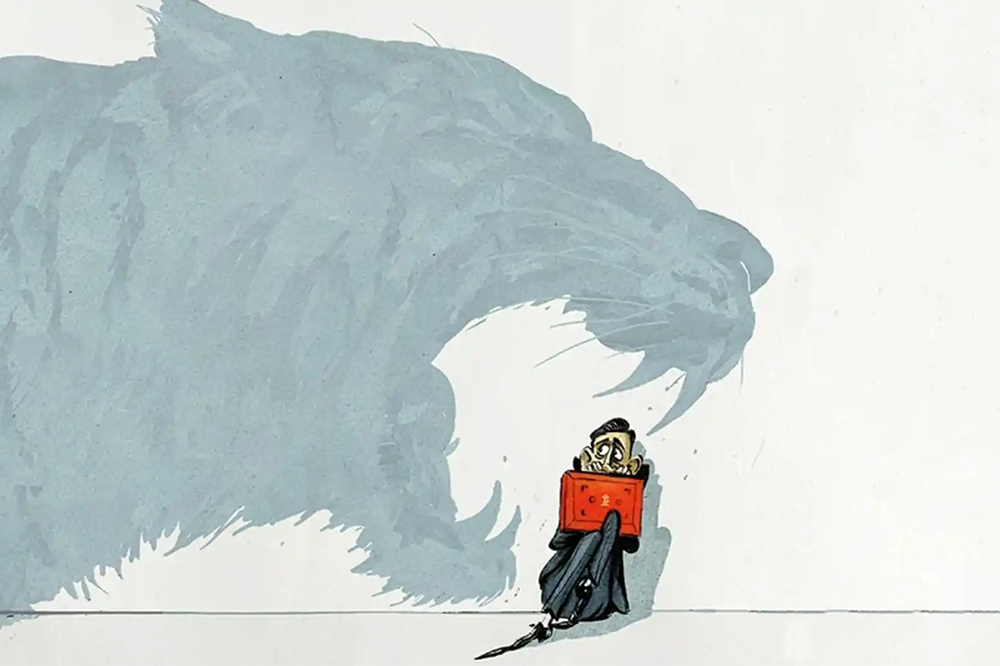

A 10 per cent increase in oil prices translates to a 0.15 per cent loss of global GDP and a rise of 0.4 per cent in global inflation, says Gita Gopinath, deputy managing director of the IMF. Before Hamas launched its assault on Israel on 7 October, the Brent Crude barrel price had already moved 20 per cent above its summer level of $75 and pundits were predicting $100, based on prospects of tighter supply from Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Natural gas prices have also risen sharply with winter approaching – and no one knows how escalation of the latest Middle East conflict might affect other energy flows and supply chains. But it will clearly add a notch to inflation, forcing interest rates to stay higher for longer, denting investment confidence and increasing the likelihood of the recession which many UK economists sense is already in the air – a sense reinforced by recent flatlining of growth and cooling in the jobs market.

But with wage rises running at 7.8 per cent, ahead of inflation at 6.7 per cent, the Bank of England economist Huw Pill understated Britishly when he told an audience in Marrakech this week that ‘we still have some work to do’ and should not ‘declare victory prematurely’. Be wary of Rishi Sunak doing just that if inflation dips even temporarily to his target of 5.4 per cent, or half its 2022 peak, in December. Put simply, there may be worse to come.

Pick people not archetypes

The fall of former Barclays chief executive Jes Staley – banned for life from senior jobs in financial services and fined £1.8 million for ‘recklessly’ misleading regulators and the Barclays board about the nature of his friendship with the convicted paedophile Jeffrey Epstein – raises the question of why Barclays recruited him in the first place.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in