George Orwell took a dim view of competitive sport; he found the idea that ‘running, jumping and kicking a ball are tests of national virtue’ absurd. ‘Serious sport has nothing to do with fair play,’ he wrote in Tribune after scuffles broke out during the Russian Dynamo football team’s 1945 tour. ‘It is bound up with hatred, jealousy, boastfulness, disregard of all rules and sadistic pleasure in witnessing violence: in other words it is war without the shooting.’

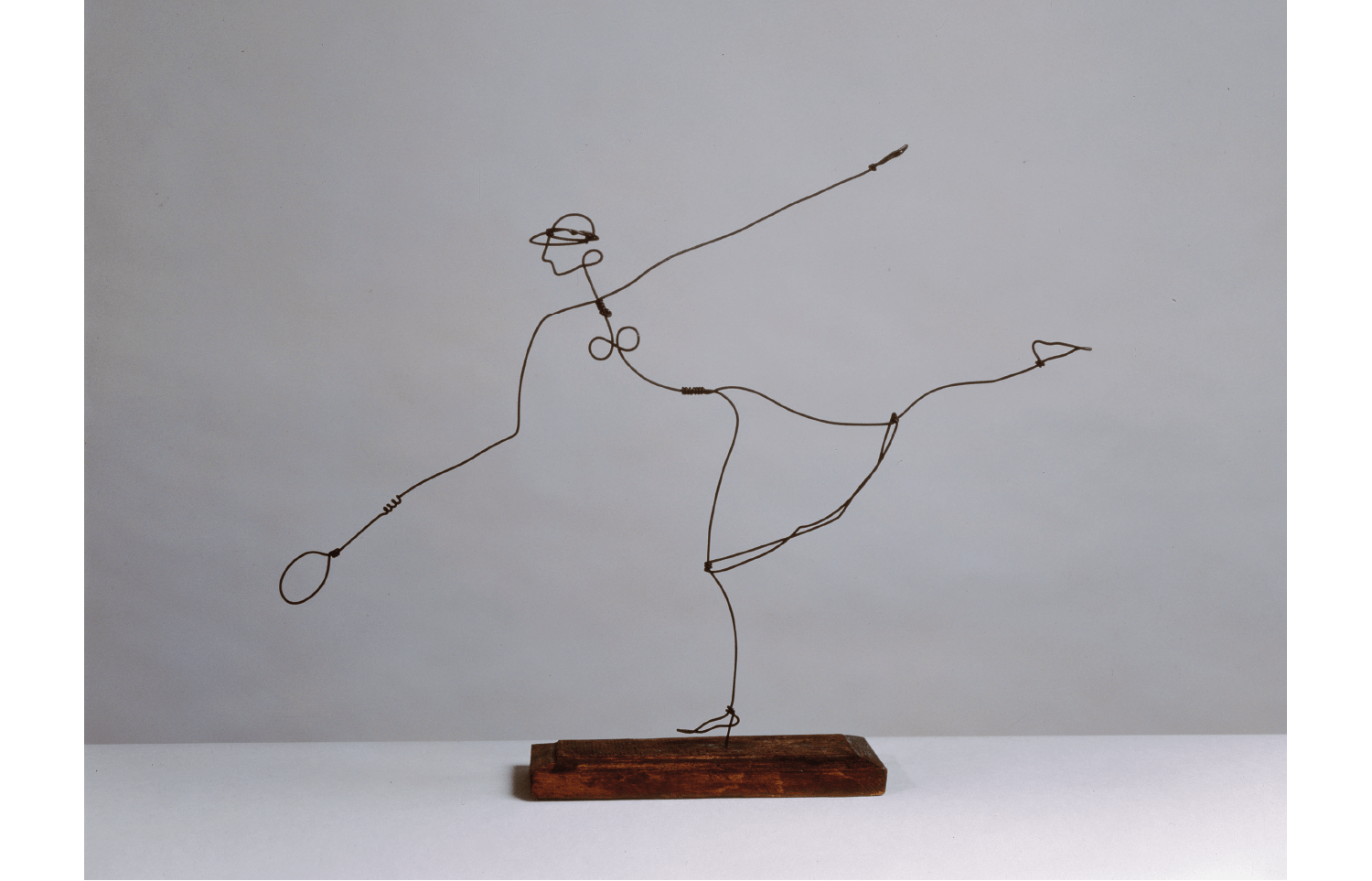

Suzanne Lenglen’s loose-fitting knee-length tennis dresses inspired the new ‘style sportif’ of Coco Chanel

Baron Pierre de Coubertin, visionary founder of the modern Olympics, took the opposite view: to him the three words ‘Faster, Higher, Stronger’ represented ‘a programme of moral beauty’. The 1924 Paris Olympics, the first truly international games and the last over which he presided as IOC president, were his final chance to realise that programme.

Though it lacked the razzmatazz of this year’s edition, Paris 1924 was more ambitious in scope. It featured an international arts competition with a roster of famous judges – the painting prize jury included Sargent, while Ravel and Stravinsky sat on the music panel. But as the Fitzwilliam’s exhibition reveals, the sporting contests had more impact on morality and aesthetics, not always in the ways de Coubertin intended.

Paris 1924 marked many firsts, not all of them athletic. African-American long-jumper William DeHart Hubbard took home the first gold won by a black athlete in an individual event and black midfielder José Andrade became the breakout star of the victorious Uruguayan football team. But the real game-changers in Paris were the women. Lucy Morton, a working-class lass from Blackpool, astonished the judges by winning gold in the 200m breaststroke – the British swimming team’s only medal – despite having lost five teeth in a Paris taxi crash. The big sensations, though, were the tennis players.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in