Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol is either, depending on your perspective, the ultimate Christmas ghost story or a complete subversion of the genre – since the tale is clearly not about the ghosts, who serve as mere ciphers in a morality tale.

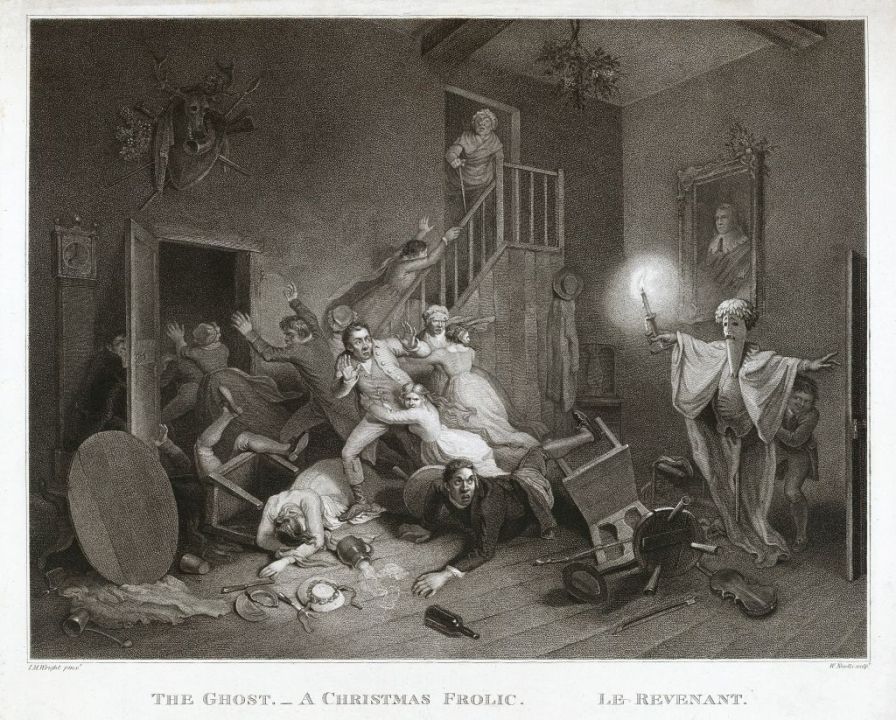

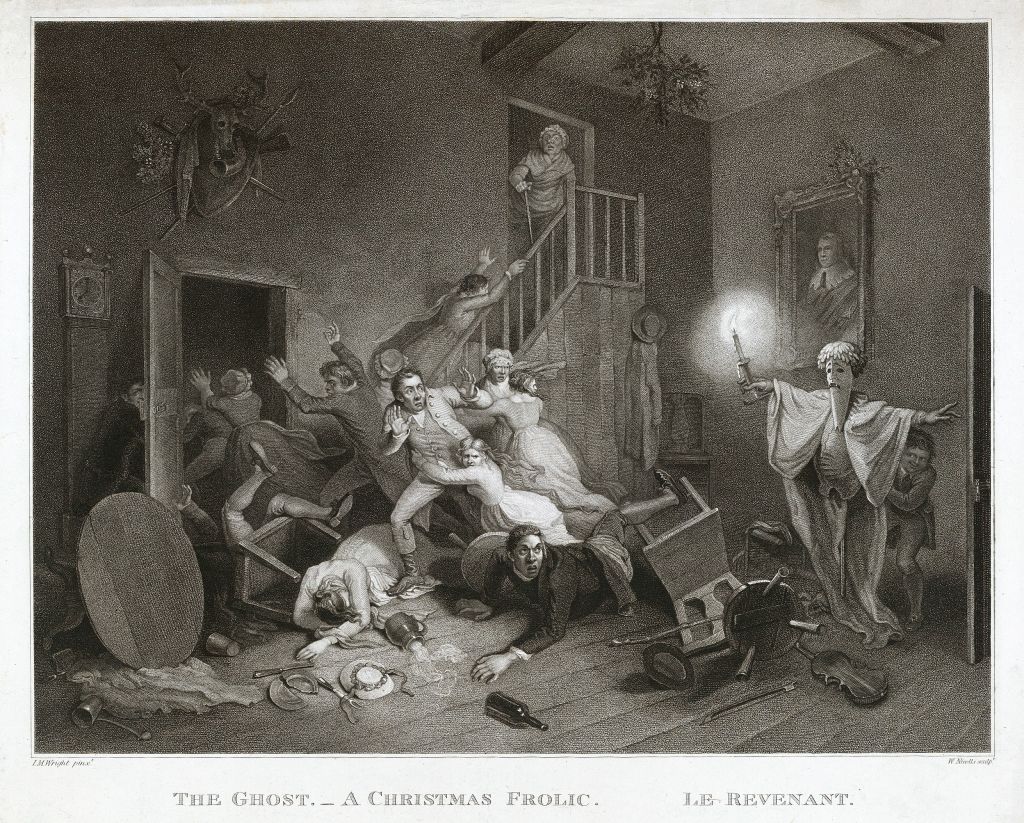

Yet in spite of the popularity of the book and its multiple TV and film adaptations, many people today are oddly unaware that Christmas was once associated, more than any other season, with the telling of ghost stories. It is Christmas, traditionally, that is the spookiest time of the year.

Tales of supernatural horror, when you yourself are in perfect safety, are perhaps as old as human storytelling itself

Christmas in its traditional sense is the Christmas season – not the period from mid-August to Christmas Eve when shops are selling tinsel and mince pies, but the Twelve Days of Christmas that begin at sundown on Christmas Eve and culminate in ‘Twelfth Night’ on the evening of 5 January. The medieval 12 nights were the ultimate stand of light and warmth against cold and darkness in the depths of Europe’s Little Ice Age. Small wonder, then, that this strange time of the year gave rise to cathartic tales of the dark, death and the macabre. The nineteenth century writer Montague Rhodes James – who used to read a chilling ghost story yearly at to a select gathering of students and fellows at King’s College – described it as the desire to be made ‘pleasantly uncomfortable’. Tales of supernatural horror, when you yourself are in perfect safety, are perhaps as old as human storytelling itself.

In a famous story recorded by Bede, the seventh-century missionary St Paulinus converted King Edwin of Northumbria by asking Edwin to imagine human life like a sparrow that flies into the king’s hall in midwinter, and for a brief moment enjoys the light and warmth of the festivities before flying again into the freezing dark: ‘So this life of man appears for a little while, but of what is to follow or what went before we know nothing at all. If, therefore, this new doctrine tells us something more certain, it seems justly to deserve to be followed’, the king declared.

And the Anglo-Saxon fear of winter is memorably evoked in Beowulf, a poem about the horrors that stalk the midwinter night:

Long was the season:

Twelve-winters’ time torture suffered

The friend of the Scyldings, every affliction… long against Hrothgar

Grendel struggled – his grudges he cherished,

Murderous malice, many a winter,

Strife unremitting…

Grendel is not, of course, a ghost – exactly what he is remains somewhat unclear – but he is an ill-favoured otherworldly visitant. The feeling that Christmas represents a struggle of light against darkness resonates, of course, with the Gospel reading for Christmas night, John 1: ‘The light shineth in darkness, and the darkness comprehended it not’. Some have linked the appearance of ghosts on Christmas Eve to the holiness of the day to follow, as if it is a last chance for dark forces to come out and play before being driven away by the light.

Christmas has long been associated with strange upheavals in nature; animals are supposed to gain the power of speech at midnight on Christmas Eve, as the entirety of nature is transformed in wonderment at the birth of Christ. As the Gaudete carol has it, Deus homo factus est, natura mirante – ‘God is made man, with all nature marvelling at it’.

But this does not seem to be enough to explain why the dead should return at Christmas time. On a basic level, we all know that grief for our loved ones is heightened at Christmas, simply because it is that time of the year when families are reunited. In the Middle Ages many people believed that there was a chance for the souls of the dead to return from Purgatory at the turning of the year in order to ask for prayers in the coming year.

Besides Dickens’s A Christmas Carol, the most famous seasonal ghost story is surely the ‘sad tale… of sprites and goblins’ started but left unfinished by the boy Mamillius in Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. ‘There was a man dwelt by a churchyard…’ In those eight words we have the essence of the medieval and early modern midwinter ghost story: the setting is the churchyard, not because churchyards are spooky (a modern idea), but because the churchyard is the resting place of the dead.

Mamillius’s story is not, first and foremost, a frightening tale but a sad one – for the souls of the dead have returned to demand the mercy of the living through the offering of prayers and masses, not to scare them.

The Christmas ghost story cathartically exorcises our fear of the spirits of the outer darkness, like Grendel – but it is also a mechanism for managing our collective grief at the loss of the departed, and a reminder to offer them their due. In this context, the morally insistent ghosts of A Christmas Carol are perhaps not as untraditional as they might at first seem.

The Christmas ghost story is far more than just a spooky bolt-on to the festive season, an antidote to tinsel and relentless good cheer. It is more than a comfortable scare. The Christmas ghost story arises from the deepest roots of the midwinter season as a time of turning, transformation and new beginnings.

Midwinter is a time of encounter with the dead; when we are reminded of their presence alongside us in our revels. The Christmas ghost stories of literature – and now TV – continue, in culturally sanitised form, an age-old and complex negotiation between light and dark, death and life, that becomes acute as the dark encroaches and daylight dwindles.

This article is free to read

To unlock more articles, subscribe to get 3 months of unlimited access for just $5

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in