Early on in Enter the Dragon our hero, the acrobatic Kung Fu fighter Bruce Lee, tells a young pupil to kick him. Needless to say, the kid’s kick comes a cropper. ‘What was that?’, Lee sneers, clipping the lad’s ear. ‘An exhibition? We need emotional content, not anger.’

Even at 12, when I first read about this scene (in the poster magazine Kung Fu Monthly, whose first 26 issues are handsomely reproduced in Volume I of Carl Fox’s Archive Series), I thought it sounded like a load of chop suey hooey. An exhibition is precisely what I’d have wanted, if by some miracle I could have wise-guyed my way into seeing Lee’s X-rated picture. Anyway, if anger isn’t an emotion, what is it? And if I’d needed any cod philosophising, I could have got it from my elder brother’s NME, thank you very much.

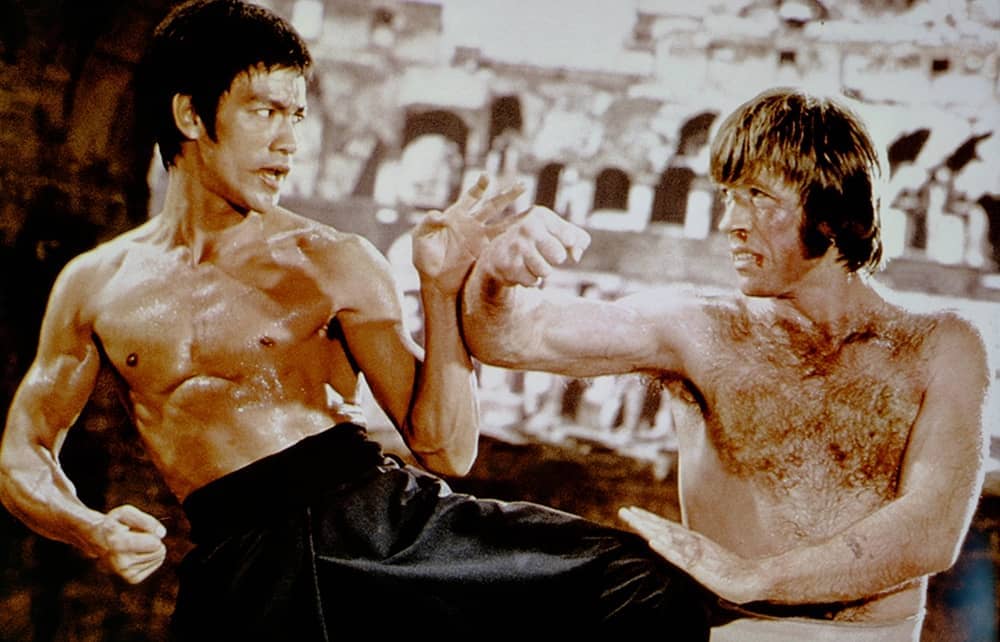

For a man who liked to break bricks with his bonce, Bruce Lee was no bonehead

But here we are, coming up to half a century since Lee’s early death (at 32 – from drugs, heatstroke, extra-marital nooky etc), and Daryl Joji Maeda, a professor of ethnic studies at Boulder University, Colorado, wants us to know that this guy was a thinker who ‘embraced Buddhist, Taoist and Confucian philosophies’. That’s right: Lee’s legacy isn’t just a handful of dopey fight flicks. The Little Dragon was as much a Heidegger as a high-kicker.

Then again, for a man who liked to break bricks with his bonce, Lee was no bonehead. Maeda has been through the notebooks Lee kept as a philosophy student at the University of Washington, and they’re not unimpressive. If Lee’s dismissal of Descartes isn’t quite final, nor is it merely fatuous. Lee had no time for dualism.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in