Among the many destructive after-effects of the pandemic, the impact of two years of lockdowns has had serious consequences for public museums and galleries, particularly so for our national museums and galleries.

More than two-and-a-half years since the last restrictions were lifted, visitor numbers to many of the big London institutions have yet to return to the levels seen pre-pandemic, according to the latest figures released by the DCMS. Although the British Museum and Natural History Museum have come roaring back, surpassing their 2019/20 figures (the NHM attracting some half a million more visitors alone), the picture varies wildly, mostly between the more ‘scientific’ museums and those whose remit is visual art.

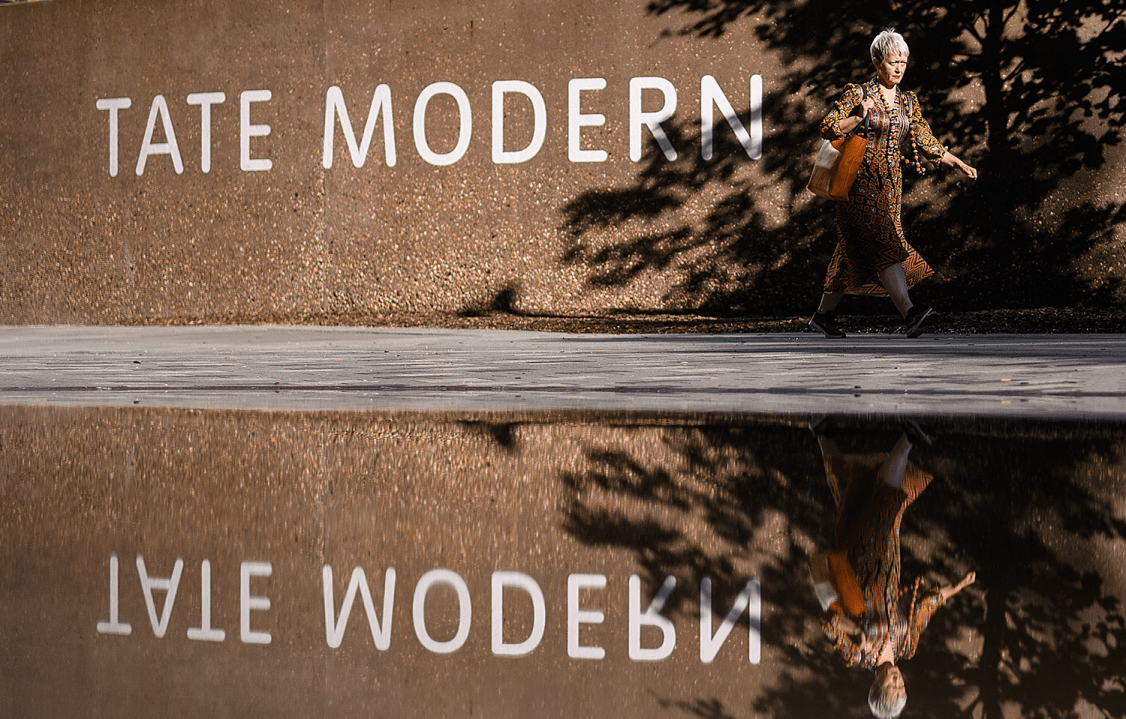

The problem with Tate’s reinvention as the gallery wing of social justice activism is the public isn’t turning up

The National Gallery, constrained since last year by its current rebuild of the Sainsbury Wing entrance (set for completion in spring next year), is still some 2.4 million below the 5.5 million of 2019. But perhaps most alarming are the fortunes of Tate’s London galleries, with Tate Modern seeing 1 million fewer visitors in the year to April than before the pandemic (5.7 million), and Tate Britain posting visitor numbers of 1.2 million, down 440,000 on 2019/20.

These figures are serious for Tate, which last year posted an £8.7 million deficit, and whose trustees approved a deficit budget for 2023-24. With visitor numbers only moderately increased, with inflation biting in increased costs and trading income down, and with Covid-related government support now ended, Tate faces some serious decisions; unless the new government swoops in with increased funding, or visitors magically reappear, Tate will have to decide what kind of cultural institution it wants to be for the next decade. Because although Tate’s travails aren’t unique among the ‘Big 6’ museums post-Covid, the fact that its audiences aren’t returning points to a bigger question about the institution’s position in the national cultural landscape.

Outside of the narrower historical remit of the National Gallery, Tate is the main national expression of the visual arts in Britain. If Tate is struggling to reconnect with the public, it suggests that the problem goes further than the temporary aftershocks of the pandemic and lockdowns. It’s in Tate’s changing priorities regarding the art it’s charged with representing – and the audiences it has chosen to pursue over the past decade – that some of the trouble becomes clear. If ‘go woke, go broke’ is an all-too-common jibe of the cultural wars era, the reality is that Tate stands out as a particularly enthusiastic convert to progressive ideological fashions, reluctant to consider that it may not be taking its public with it.

One of the more ambivalent consequences of Tate Modern’s enormous success since it opened in 2000 has been the relative sidelining of Tate Britain. The gallery is charged with the care of the Tate’s historical British collections but has been stuck with the awkward job of representing modern British art while Tate Modern’s remit also claimed modern art at the international level. The split has left Tate Britain with a sort of ongoing identity crisis, as if playing second fiddle to the behemoth on Bankside.

While Tate Modern was confidently riding the cultural enthusiasm for contemporary art that characterised the 2000s and early 2010s, Tate Britain was saddled with the unfashionable old stuff, over two decades in which Britain’s history and sense of national identity have come increasingly under attack. It was Tate Britain’s previous director, Penelope Curtis, who began presenting the history of British art as critical revision of social history, with shows such as Migrations: Journeys into British Art, Art Under Attack: Historics of British Iconoclasm, Artist & Empire and Queer British Art conceived during her tenure.

Curtis departed in 2015, after a backlash by prominent newspaper critics including Brian Sewell and Waldemar Januszczak, but Tate Britain’s social justice-tinted view of history has continued, not least with last year’s rehang of the permanent collection, delayed by Covid, in which preoccupations with Britain’s colonial and imperial history, the representation of women and people of colour, and depictions of social class have become the main narrative thread. That this social history does little to offer visitors an understanding of the aesthetic and stylistic evolution of art in Britain seems to pass Tate Britain by. So while mediocre paintings can be wheeled out to make a point about the position of black people in Georgian and Victorian Britain, popular and artistically significant modern paintings, such as Stanley Spencer’s 1924-7 ‘The Resurrection, Cookham’, long on display, can be packed off to the storerooms for the crime of not conforming to contemporary curatorial sensitivities about how people of colour should be represented.

No doubt Tate Britain would dispute that there’s been anything wrong with its recent reinvention as the art gallery wing of social justice activism, but the fact is that the public isn’t turning up. At the time, Curtis was lambasted for seeing visitor numbers fall under her watch, but they have fallen even further in the years that followed. Tellingly, it was 2017, the year of David Hockney’s retrospective, that drew the crowds. More tellingly, Tate Britain hasn’t staged a similar monographic show of a significant (meaning recognisable and popular) postwar British artist since.

Tate posted an £8.7 million deficit last year and approved a deficit budget for 2023-24

Tate Britain’s identity crisis is only one part of Tate’s wider move towards progressive cultural and social agendas that, whether well-meaning or not, have the effect of splitting the gallery’s public into separate identity groups, promoting shows that it assumes will attract particular demographics. This shift has been a strategic choice. In her recent book on the role of the contemporary museum, Gathering of Strangers, director Maria Balshaw is fully signed up to the idea of the museum as an engine of social activism, historical decolonisation and environmental advocacy. What doesn’t figure so much is any interest in Tate’s relationship to the national story, the term ‘nation’ barely figuring at all, Balshaw’s view of society jumping from the ‘international’ to the ‘hyperlocal’, with a sort of blindspot where the ‘national’ should be, fixated with ‘diversifying’ the audience to include the underrepresented. And yet still they fail to come through the doors.

Balshaw’s view of the museum is a diminished one. By the book’s end, she is arguing for the ‘degrowth’ of the museum, musing that deaccession (getting rid of artworks) may be a good thing, chiding other museums that insist on maintaining the ‘best conditions’ for the preservation of the objects in their care without thought to the energy consumption required, and questioning if the ‘blockbuster’ show isn’t overrated, since they tend to be of ‘familiar, usually dead, white and male, artists’. ‘Is quantity our best measure for good?’ Balshaw wonders.

Considering the relative merits of quality and quantity would be fine, as would extolling the fashionable virtue of ‘degrowth’, if your numbers weren’t so bad, you weren’t running a deficit and were scrabbling for funding. According to one attendee of a recent meeting of Plus Tate – the partnership network of Tate and more than 40 UK visual arts venues (mostly Arts Council-funded) – when the idea of lobbying the new government for increased funding was mooted, Balshaw was allegedly quick to discourage this, suggesting that Tate’s financial concerns should take priority. Degrowth is fine… for other people.

While cutting funds or shrinking the activities of great cultural institutions is never a good thing, it’s time for a big debate about what Tate thinks it’s for, who it’s for, and where it’s going.

Comments