The chess lexicon has adopted a useful word from German, fingerfehler, fehler meaning mistake or error. Sometimes, the hand does not obey the brain. Imagine that you are busy contemplating A, followed by B and then C, and engrossed by the consequences of C. Meanwhile, the hand is eager to get involved, and picks up the piece to make move C. Standard competition rules are that once you’ve touched a piece, you must move it, so even if you catch yourself before executing the move, the damage from picking up a different piece may be terminal.

Mercifully, I don’t recall ever doing this, but I’ve come close enough to know that the phenomenon is real. That’s my understanding of fingerfehler, although I’m just as often mildly frustrated to hear the word used interchangeably with ‘blunder’, sometimes by a player who would sooner blame their physiology than admit that their intended move was a straightforward howler.

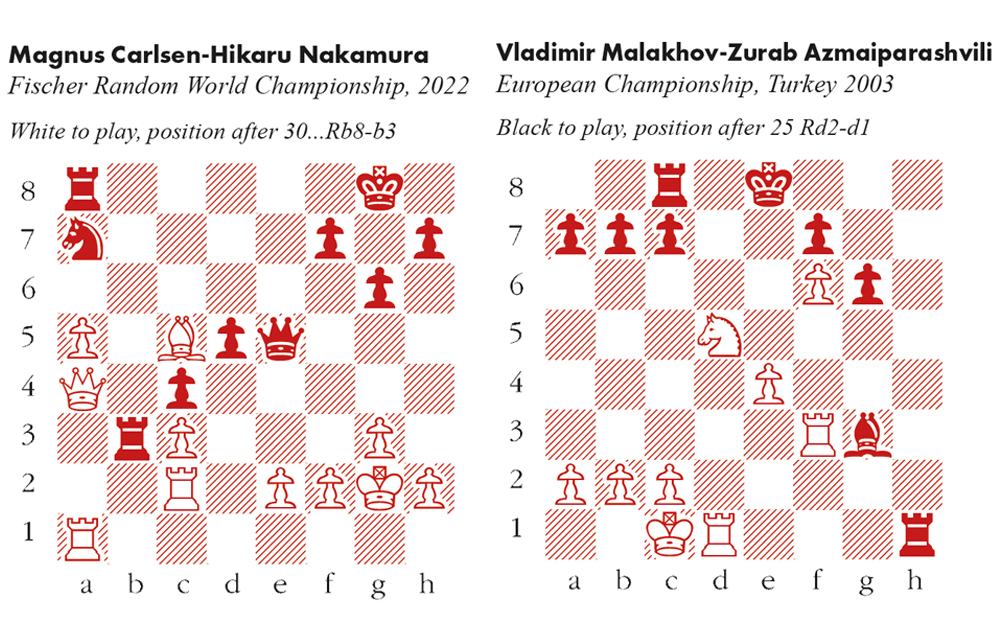

It happened in a game at the Fischer-Random World Championship last month. In the diagram above left, Magnus Carlsen played 31 a6?? and Hikaru Nakamura responded with 31…Qe4+, forking the king and rook. It was an extraordinary mistake for a player of Carlsen’s calibre, who explained to Nakamura that he had been thinking about 31 f3 Nb5 32 a6, which was indeed the strongest sequence in the position. After losing his rook, Carlsen struggled on for a few moves, but the result was never in doubt.

A famous fingerfehler occurred on the top board at the European Championship in 2003. (On that day, I was playing against Alexander Grischuk on board 4.) Reaching the position in the second diagram, Zurab Azmaiparashvili intended to exchange rooks on d1 and then flee with the bishop, but his hand picked up the bishop first.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in