Port, or Hermitage? This does not refer to personal consumption. I was trying to remember Meredith’s Egoist, in which one of the principal characters seeks to coerce his daughter into marriage, in order to have unlimited access to his putative son-in-law’s ancient wines. That could give rise to an interesting moral speculation.

I raised the question in a club, one of the few surviving places in Britain where free speech is possible. There was a desire for further and better particulars: which wine were we talking about, and what about the daughter? Was she an easy-on-the-eye, generally obedient creature, a pleasure to have about the place, or…. Someone quoted Lord Tottering, from one of those splendid cartoons in Country Life. At a party, Tottering and a chum are confronted by a roomful of gyrating teenage females. His Lordship comes to a conclusion: ‘The number of daughters a chap has must be related to his wickedness in a previous existence.’

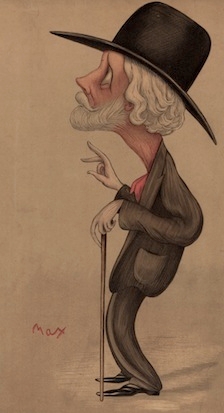

There was a cautious endorsement of trading daughters for wine, and the subject gave rise to merriment, which is more than Meredith does. Few reputations have plummeted so totally, so irrevocably: so deservedly. He is all strain and no effect. His earnestness may have enabled him to slip below the late Victorian radar. They were used to long sermons. But the tedium. His contemporaries rated him with Dickens and Eliot. Why? He is defective in plot, narrative and characterisation. He cannot write a decent sentence. ‘Comedy is a game played to throw reflections upon social life,’ the book begins. Meredith is incapable of humour, he has no understanding of society and his reflections are worthless. There is one vaguely entertaining character, a boy called Crossjay Patterne: a cross between Mr Midshipman Easy and William Brown, a few respites of light relief.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in