There can be no clearer illustration of the central role that great cathedrals continue to play in a nation’s life than the outpouring of grief that greeted the catastrophic blaze in Notre-Dame in 2019. President Macron described the building as ‘our history, our literature, our imagination, the place where we experienced all our greatest moments’. Indeed, it is impossible to conceive of any major European city without a cathedral at its heart.

Emma J. Wells has written an accessible, authoritative and lavishly illustrated account of the building of 16 of ‘the world’s greatest cathedrals’. Her subjectivity is evident in that only seven feature among Simon Jenkins’s top 25 in his Europe’s 100 Best Cathedrals, although those seven – Amiens, Canterbury, Chartres, Cologne, Paris, Wells and Winchester – would surely be included on anyone’s list.

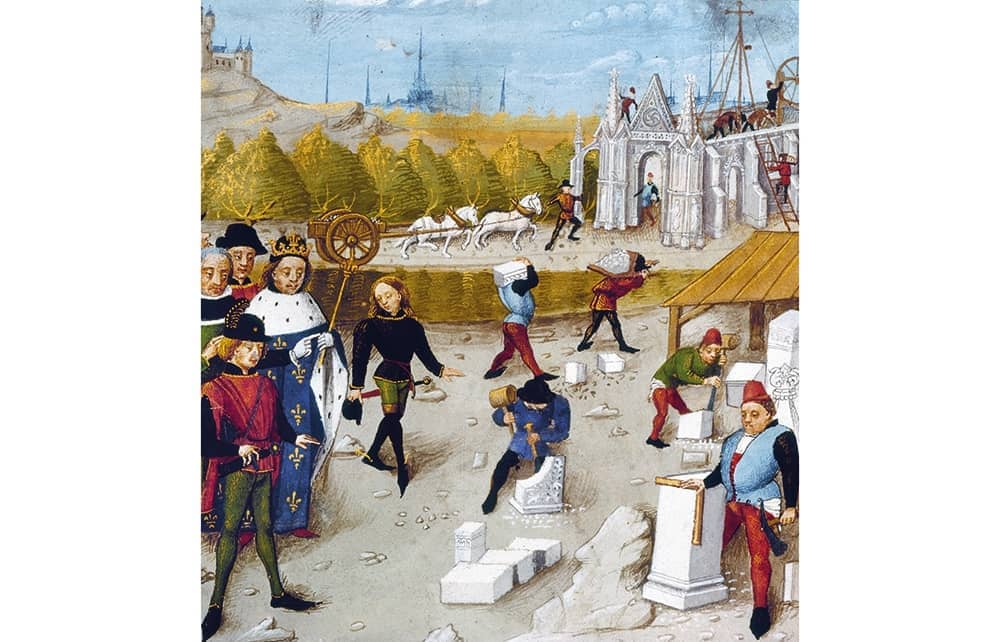

Several cathedrals received supernatural visitations while being built – Cologne’s from the Devil

Heaven on Earth begins with the Byzantine Hagia Sophia in Istanbul and ends with Brunelleschi’s Renaissance dome for Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. But the author’s primary focus is on the Gothic, which developed from the ogives, ribbed vaults, flying buttresses and stained glass of Abbot Suger’s Saint-Denis. Although disparaged by later writers such as Vasari, the Gothic style was designed to be ‘the metaphorical and physical exemplar of the Celestial City, the Heavenly Jerusalem’.

Some complex factors are explored: political unrest (Hagia Sofia), territorial ambition (Santiago del Compostela), pilgrimage envy (Westminster Abbey) and, above all, fire (Amiens, Rheims, Chartres and Canterbury) that led to these cathedrals’ existence in their present form. It charts their multifarious roles as landowners, courts, economic powerhouses and presenters of pageants and processions.

Chartres and Salisbury, their basic structures completed in 26 and 40 years respectively, were anomalies.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in