The pandemic is not quite over, but we are getting used to its inconveniences. What disaster will be next? An antibiotic-resistant strain of the bubonic plague? Climate collapse? Coronal mass ejection? Will the next catastrophe be natural — perhaps a massive volcanic eruption, the likes of which we have not seen for more than two centuries, since Tambora in 1815? Or will it be a man-made calamity — nuclear war or a cyberattack? And might we inadvertently descend into a new form of AI-enabled totalitarianism in our efforts to ward off such calamities?

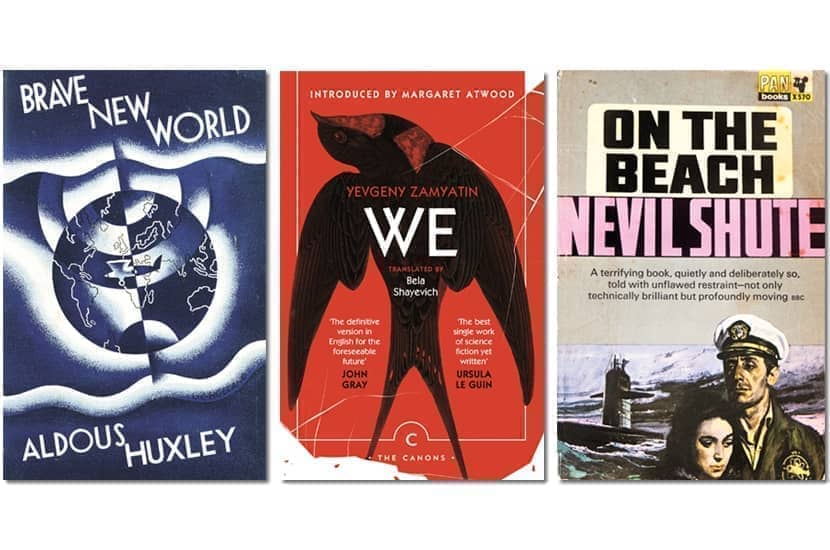

To all these potential disasters it is impossible to attach more than made-up probabilities. So what can we do about them? The best answer would be that we should strive to imagine them. For the past two centuries, this has been the role of science fiction. Dystopias are histories of the future. This sounds like a contradiction in terms, but as they have always echoed present fears (or, to be more precise, the anxieties of the literary elite), they show us which worries of the past had a role in history. As Fahrenheit 451 author Ray Bradbury once said: ‘I am a preventer of futures, not a predictor of them.’ But how many policy decisions have been influenced by dystopian visions? And how often did these turn out to be wise ones?

The 1930s policy of appeasement, for example, was based partly on an exaggerated fear that the Luftwaffe could match H.G. Wells’s Martians in destroying London. More often, though, nightmarish visions have failed to persuade policymakers to act. Yet science fiction has been a source of inspiration, too. When Silicon Valley began thinking about how to use the internet, they turned to writers such as William Gibson and Neal Stephenson. Today, no discussion of artificial intelligence is complete without reference to 2001: A Space Odyssey, just as nearly all conversations about robotics include a mention of Philip K.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in