How time flies when there’s a real crisis. Just six months ago at the Glasgow climate conference, the Chancellor Rishi Sunak was pledging to rewire the entire global financial system for Net Zero. Sunak boasted that he was going to make London the world’s first ‘Net Zero Aligned Financial Centre’. It would mean forcing firms to publish plans showing how they will decarbonise and meet net-zero targets to be overseen by a transition taskforce. There was little fanfare when the transition plan taskforce was launched last week. Even though the taskforce is co-chaired by John Glen, the economic secretary to the treasury minister alongside the chief executive of Aviva, you won’t learn much about the taskforce from the Treasury website, which, however, does tell us which artist is going to design a new £1 coin.

The Treasury’s recently acquired modesty about blazing the net zero finance trail is explained by the energy crisis that threatens to overwhelm the economy and the government with it, just as the first energy crisis did for the Heath government in the early 1970s. The Chancellor now whistles a different tune. He is demanding that Shell and BP use their record profits to increase their investment in the North Sea to avoid being hit by a windfall profits tax. According to a heavily briefed report in the FT, Sunak wants oil and gas companies to raise their capital spending on UK projects to boost the country’s energy self-sufficiency. Wind and solar are not substitutes for oil and gas. Sunak’s goal of improving self-sufficiency therefore implies he wants more investment in fossil fuel production. But, as the FT notes, investment in the North Sea by energy companies has fallen 90 per cent since 2014.

High oil and gas prices should induce a supply-side response. In the past, they led to increased investment, which in turn led to increased output and falling prices. This time is different. Institutional investors managing over $130 trillion of assets have signed on the dotted line of the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero: ‘an historic wall of capital for the net zero transition,’ Sunak told the Glasgow climate conference.

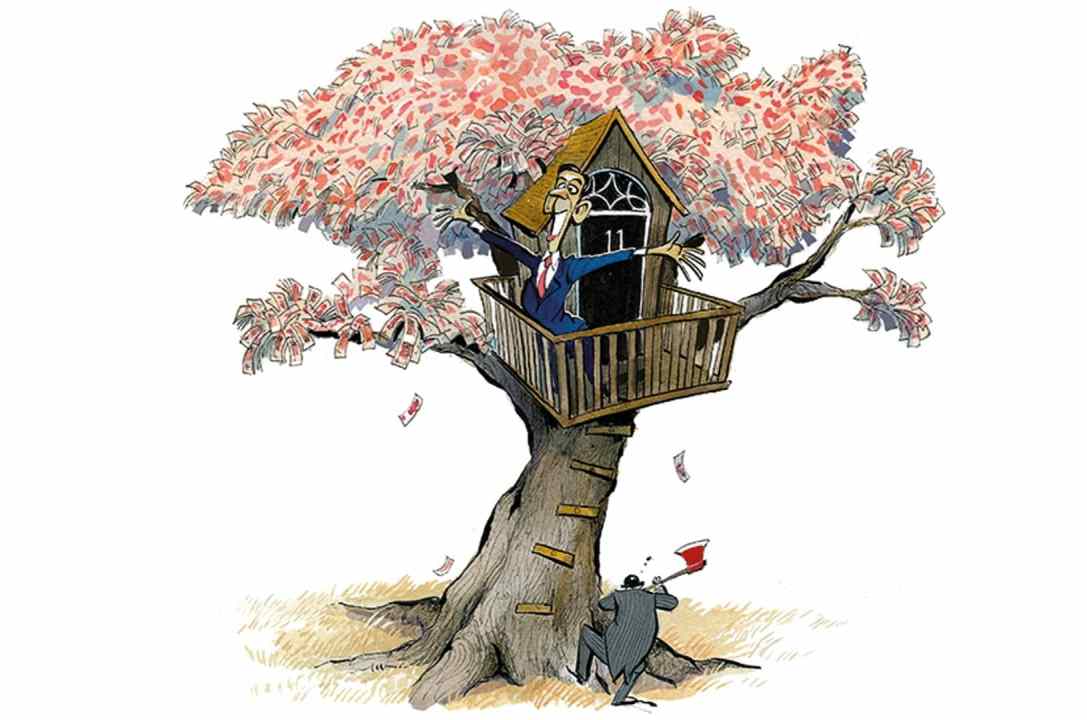

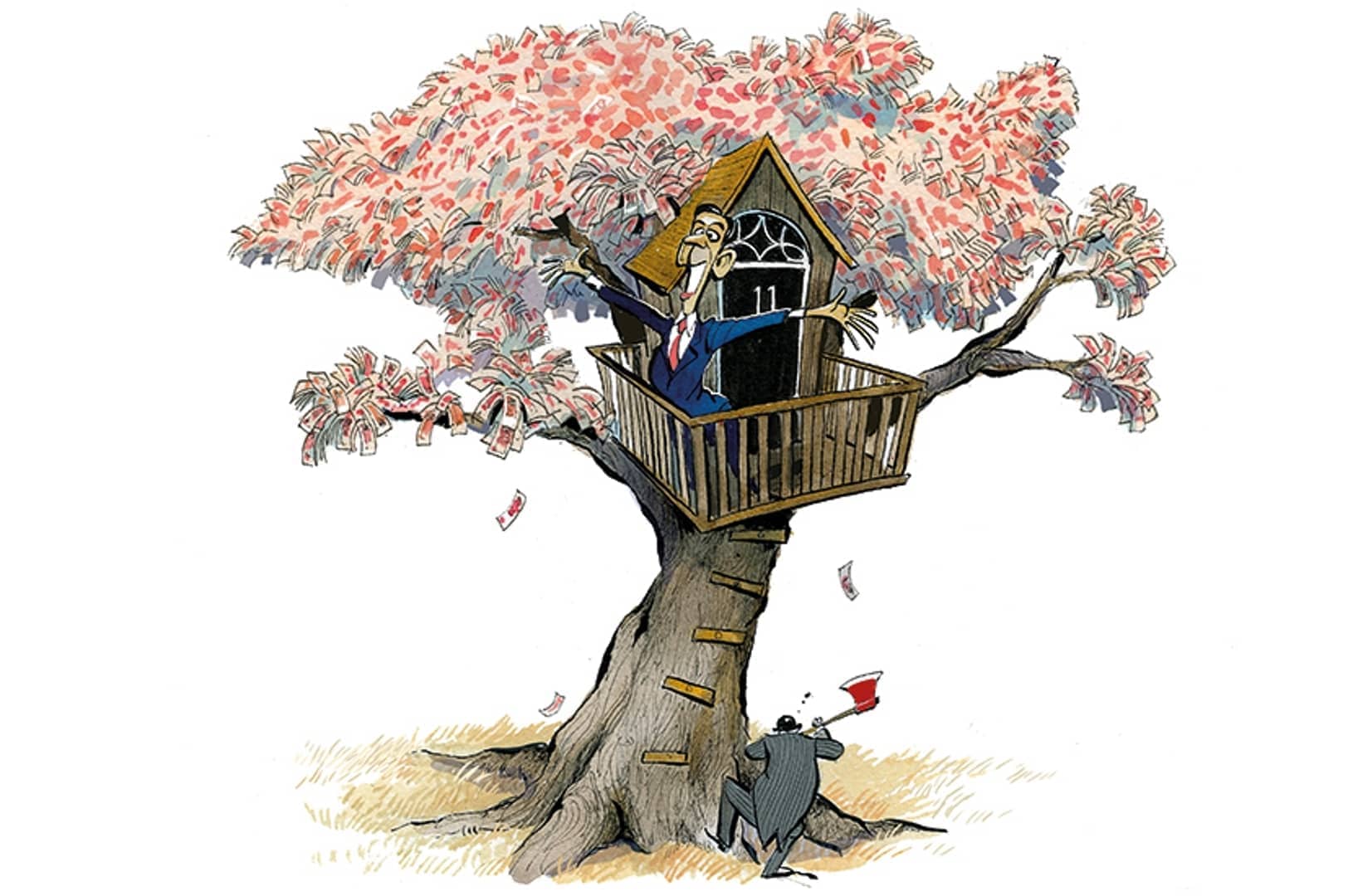

Garnering plaudits at a climate conference comes at a high cost

Last year, the Paris-based International Energy Agency (IEA) issued a net zero roadmap. Its net zero pathway meant that no new investment in oil and gas production was needed. Despite having got its predictions of flat or falling oil and gas prices horribly wrong, the IEA’s mantra of no new oil and gas investment has been adopted by investors to justify strangling the flow of capital needed to boost supply, bring prices down and enhance the West’s security. We are now seeing the folly of letting Western investors effectively impose an energy investment embargo on the West. At some level, the Chancellor appears to recognise this, or at least something of it. Having been a cheer-leader for net zero finance and setting up a process for punishing companies for not having net zero transition plans, he now threatens oil companies with windfall taxes if they don’t invest. It’s a plain and obvious contradiction.

But garnering plaudits at a climate conference comes at a high cost: Sunak is trapped by his Glasgow speech, which was far and away the worst speech given by any Conservative Chancellor of the Exchequer. It is profoundly unconservative to advocate the socialisation of people’s savings, as the Chancellor did when he said he wanted to rewire the financial system around achieving net zero. Pumping capital into politically-favoured sectors is a formula for stoking an unsustainable financial bubble, such as in housing finance, which was the root cause of the subprime mortgage blow up and the 2008 financial crisis. If his Glasgow climate speech was bad at the time, it reads even worse in the light of Vladimir Putin’s attack on Ukraine, which adds a strategic imperative to an economic one of letting capital markets freely invest in new oil and gas production.

There is huge momentum behind net zero investing – encouraged by central banks and financial regulators – that has nothing to do with financial returns. The willingness of institutional investors to deepen the current economic crisis and undermine the strategic interests of the West is a new problem brought about by the rise of Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG)-investing that has swept the world of finance.

The doctrine underlying ESG and stakeholder capitalism asserts that businesses must be responsible to society. The corollary is that businesses and their investors are responsible for society. By encouraging ESG, politicians like Sunak outsource societal decisions and societal decision-making to financiers. Governments, not financiers, are held accountable by voters for the performance of their economies. Governments, not financiers, are responsible for national security.

Nonetheless, politicians find it convenient to have the City do the heavy lifting on climate policy. There is no substitute for politicians imposing draconian policies to suppress demand for oil and gas. These will be deeply unpopular. The government reckons the shadow price of carbon to meet net zero is £248 per tonne of carbon dioxide in 2020 money. Imposing a £248 per tonne carbon tax would be swift and sure way of committing electoral suicide. But without demand suppression, the effect of banks and investors curtailing investment by western oil and gas companies means demand is met by a combination of much higher prices and supplies from state-owned oil and gas companies such as Saudi Aramco and Gazprom.

As inflation keeps on rising and the cost of living crisis intensifies, the perversity of investor-imposed net zero policies will become increasingly untenable. These will continue until a politician has the courage to say ‘Stop.’ What we’ve learnt this week is that politician will not be Rishi Sunak.

Rupert Darwall is a senior fellow of the RealClear Foundation and author of Green Tyranny

Comments