Twenty-odd years ago, while on holiday in the deep Mani at the foot of the Peloponnese, I got into conversation with an old and only partially reconstructed Greek communist shop-owner. I had been showing him a bit of pottery I had found on the sea bed at Asomati, and he wanted to know what had brought me to the Mani in the first place and was it Patrick Leigh Fermor? I said no — not strictly true — and he seemed pleased. Leigh Fermor, he said — and he was not prepared to elaborate — had not been good for Greece.

It came as something of a surprise, as in those days at least Leigh Fermor’s writ seemed to run the length and breadth of the Mani — you could have filled a division with the old men who claimed to have fought alongside him in Crete — but the shop-owner would certainly not have been alone. From the days of Byron and the scandalous ‘Greek loan’ of the 1820s Greeks have always had good cause to be wary of Englishmen bearing gifts. And the villagers of Crete during the second world war — who had to watch their houses burned and their men executed in reprisal for one or other SOE action — had every bit as much reason to wonder as their ancestors had whether British help was worth the cost — who had seen the gold destined for Greece disappear into bottomless City pockets back in London.

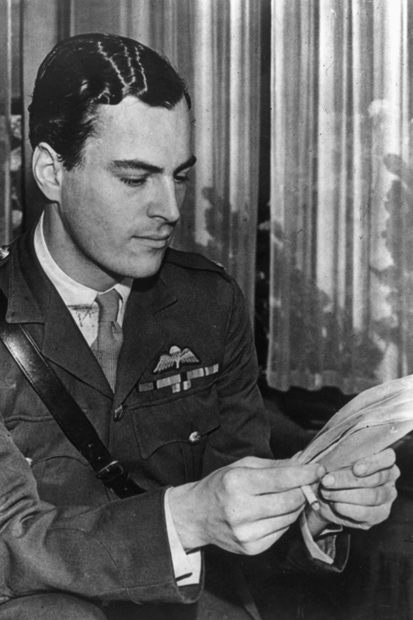

‘What a queer set,’ the great American doctor and philanthropist, Samuel Gridley Howe, famously wrote of the phil-hellenes who swarmed after Byron to fight for Greek freedom: ‘What an assemblage of romantic, adventurous, restless, crack-brained young men.’ And in the men of the Cretan branch of the SOE we have their natural successors.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in