It’s sometimes said that if Wagner were alive today he’d be making movies, but come on – really? A generation of Wagnerites has grown up for whom the first and definitive encounter with Der Ring des Nibelungen was on the small screen – in my case, the BBC’s early-eighties serialisation of the Bayreuth centenary production. What lingered was not the spectacle, but the intimacy: Donald McIntyre and Gwyneth Jones enveloped in darkness, reaching into each other’s souls. If you grew up with Wagner on TV and came of age, culturally speaking, around the time The Sopranos first aired, it seems obvious that the Ring isn’t some effects-laden Marvel blockbuster before its time, but the world’s first long-form TV drama.

For evidence, look at the proliferation of small-scale Rings since 1990, when Jonathan Dove first produced his pioneering (if heavily cut) Birmingham version for just 18 players. Ben Woodward, the conductor of Regents Opera’s ongoing Ring at the Freemasons’ Hall has opted for an orchestra of 24, using the Hall’s organ to beef up the climaxes and thicken the darker textures. He’s taken care to obscure the attack of its main entries, so you only rarely perceive the characteristic organ tone and, in fact, barely notice its presence until you feel the air quivering and wonder how such a small ensemble can be making such an expansive sound.

The Ring isn’t a Marvel blockbuster but the world’s first long-form TV drama

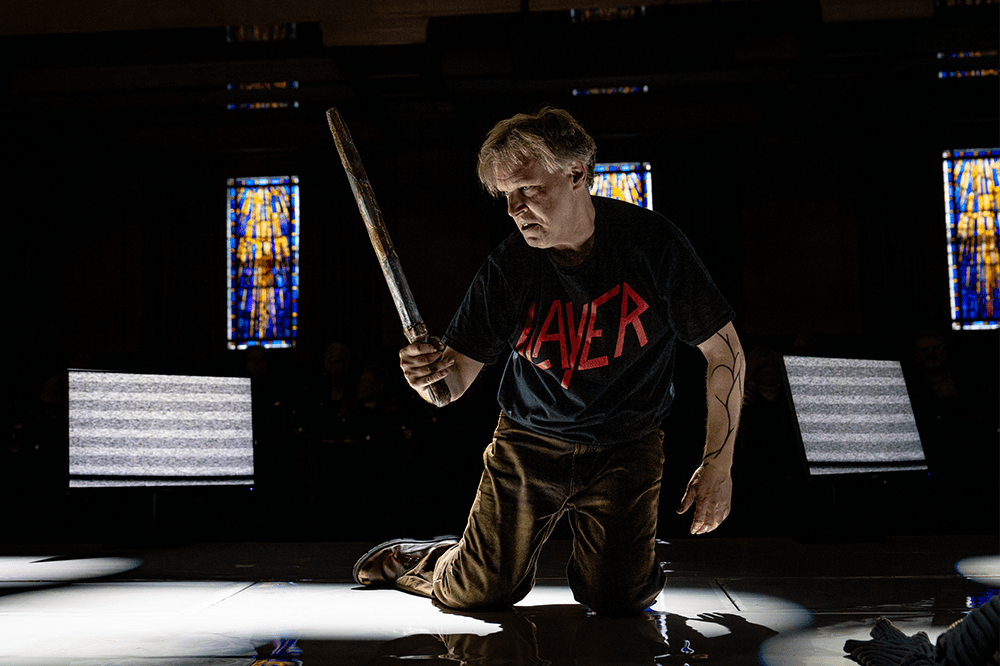

This Siegfried was my first encounter with the Regents Opera cycle. Caroline Staunton’s production is (unfortunately but probably unavoidably) performed in the round, though surtitles are provided and she makes imaginative use of the hall’s various exits and entrances. The sets, designed by Isabella van Braeckel, are minimal and portable, with a Tate Modern vibe: a lightbox for Fafner’s cave, video screens for the forest and a Marcel Duchamp sculpture as Siegfried’s anvil, though the sight-lines in the venue made it difficult to see anything below waist height.

Against those caveats you’ve got Woodward’s masterly pacing, the passion of the orchestral playing and a distinctly urban production concept which is no sillier than anything you’d see in a major house these days.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in