Some 160 million will have watched Britain staging a successful Eurovision Song Contest in Liverpool: the world’s most-watched non-sporting TV event. But our own act, Mae Muller, finished second-last. Had it not been for a generous vote from Ukraine’s jury, we’d have been last. It’s a familiar trend. With the spectacular exception of Sam Ryder last year, our entries have tended to flop badly – leading to questions like ‘Why did the BBC pick another dud act?’ and ‘Why does everyone hate Britain?’ But we struggle at Eurovision for a number of systemic reasons, all of which come down to the way we lazily pick an act and give them none of the practise that other countries have. Every year, our singer is sent naked into battle.

A winner needs to cross several language barriers and get it right on choreography and camerawork. It requires a level of preparation (ideally through a televised song-selection process) that the UK never bothers with. Perhaps because we have the best musicians in Europe, arguably the world, we don’t really try in Eurovision: seeing it as the equivalent of a musical bad-taste party rather than recognising it as a genre – schlager – loved by millions worldwide. We fail because we don’t really try. This isn’t the fault of the singer, but the system behind our singer.

- The UK does not bother with a selection contest. Our act is chosen by a BBC-convened committee. But it’s hard for any committee, no matter how famed or illustrious, to pick a musical winner. Without testing a number of entries for real in a selection contest, you have no idea how the combination (song, stageplay, camerawork) will go down with a TV audience. Sweden’s recent run of Eurovision success is no mystery. Every year it runs Melodifestivalen where 17 entries are whittled down via a final and a ‘second change’ final with a mass audience (2m votes) and a foreign jury convened. That’s why Sweden is usually the favourite to win Eurovision before its entry is known: it takes care with the process. The UK does not. So the risk of our entry misfiring is far, far bigger.

- The UK act isn’t even required to get through a semi-final. We’re guaranteed a place in the final because we give so much money to the European Broadcasting Union. This so-called Big Five status (along with France, Italy, Germany and Spain) has the years has allowed us to send in awful acts that would not have passed an earlier qualifier. So excellent acts like Ester Peony’s On a Sunday (Romania, 2019) don’t make it through, while junk like Engelbert Humperdinck does. The UK is therefore more likely to finish last because the other acts have already won some kind of vote. So if you make it to the final with an act that the semis would have filtered out, you’re more likely to come last. As Germany did. Its awful entry would never have made it through the semis, so stood badly exposed on the night.

- The UK entry seldom charts at home. At one point this year, the entire Swedish top ten were entries from its Eurovision contender lineup: that’s a massive and genuine national endorsement. Most years, the UK entry never hits the top 100 let alone the top 40. That’s not the case this year: Mae Muller hit no. 3, but her heavily-produced radio edit was not reproduced live. The camerawork was a mess. Eurovision doesn’t let artists mime, or use live-autotune. You need someone who can (as Loreen did) hit and sustain the top notes while pulling off the choreography. So while a song that charts at home is a good sign, it’s not a sure sign.

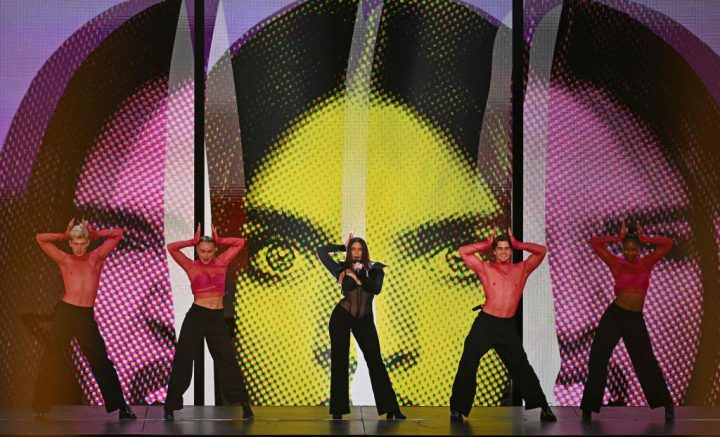

- The UK candidate never gets proper prep. By the time Loreen sang ‘Tattoo’ in the final, she had performed it four times in front of a national television audience (three times in Sweden, once for the ESC semis) and honed her camera angles. The Swedes have this down to such a tee that they even wrote a song about how to win Eurovision: ‘Look into the TV camera, so the audience will see / that you’re loveable, not desperate. Smile: and they will vote for me.’ An audience of millions will be watching with crisps and drinking games as the acts get going, often in a language most watching don’t understand. So the choreography needs to tell a story and do what words cannot. Eurovision is more multi-factorial than any other musical event: there’s a huge amount to practise and perfect. This year, Loreen was in a rage after the Liverpool stage offered fewer camera angles: Sweden worked on that and sorted it between the semis and the final. The UK act is never given this level of attention or support. From the BBC postmortem it seems to be only dawning now that the camerawork was off (“the liberal use of wide shots and Pop Art video installations meant TV audiences couldn’t always appreciate the singer’s cheeky charisma”). If she’d been through a UK selection process, or the semis, this penny would have dropped earlier. The first time a UK artist performs for real is also the last time.

- The UK seldom thinks about the politics of its entry. Eurovision is, at its core, a collision of music, culture and politics. Dana won for the UK in 1970 because her native Bogside was ablaze during the Troubles, but here was a teenager singing about raindrops and roses and whiskers on kittens. The juxtaposition was just powerful with West Germany’s A Little Peace during the Cold War in 1982. Israel’s offer of 12 points then marked a moment in the rapprochement between the two countries. Czechia had a Ukrainian verse in its 2023 song. Eurovision entries often seek to articulate the historical moment. Demographics play a large part, too. Norway’s 2009 victory – which brought the biggest margin in Eurovision history – came when they selected a Minsk-born fiddler with a Slavic riff, thereby hoovering up both the Slavic and Scandi votes. Loreen is Swedish-born to a Moroccan family: an appeal to a country’s multicultural credentials is often effective. Then there’s competing styles: you need to anticipate European trends and know how to stand out. Zelmerlow won for Sweden in 2015 by pioneering live digital choreography. Portugal took the gold in 2017 by detecting the rising European emphasis on national identity and fielding a gentle singer-songwriter with an acoustic entry that smashed the old rule that ‘winners sing in English’. It’s pointless to complain that ‘Eurovision is so political’. Yes, it is: and success goes to countries who best adjust to the fact.

I once took part in a discussion in the Swedish embassy asking why, given the UK is a musical superpower in every genre, we can’t churn out winners. We are home to Dua Lipa, Adele, Harry Styles, Ed Sheeran. We boast the Proms, the West End, Celtic Connections: we’re the European capital of every style of music you might imagine. London is a magnet for the world’s best singers, writers, producers. Our capital is crawling with executives who know how to lay on a show for anyone, anywhere. But they take selection and training seriously, in a way that BBC simply does not.

Perhaps the BBC judges that it’s not worth the effort: that the UK is a musical superpower and don’t need to be serious about the schlager-fest staged by the continentals. (I feel confident that the comments section below this article will given an example of the strong, often visceral British line that Eurovision is camp junk.) The BBC hates the idea of running a talent contes as its executives struggle to find one half-decent act, let alone the 18 they’d need. In which case, there is an alternative.

ITV is also a member of the European Broadcasting Union and does better with grassroot talent contests. The BBC’s specialism is celebrity/VIP based shows: Strictly, the coronation etc. So next time, ITV could choose an entrant (a task the BBC seems to hate) while the BBC presents the final. It did a magnificent job last night: the video footage between the acts demonstrated the shared culture between Ukraine, the UK and every entrant. The interval acts were often excellent and the presenters lively. Some day, the UK may again decide to actually compete in the world’s most-watched musical contest – lay on a decent selection process that gives our acts decent support. Until we do take our act seriously, we should not be surprised if those watching don’t really take it seriously either.

Comments