While I was reading Most Delicious Poison, I visited a herbal garden in Spain which features the plants grown by the Nasrid rulers of Granada hundreds of years ago. They cultivated myrtle for its medicinal uses and jasmine for its fragrance. How did they know of myrtle’s properties? Some ancient ancestor must have figured it out. And that ancestor might be more ancient than we realise. Noah Whiteman explains that DNA from plants found in Neanderthals’ teeth tartar suggests even they were self-medicating with herbs. We have been entangled with the chemicals around us for as long as we have been human.

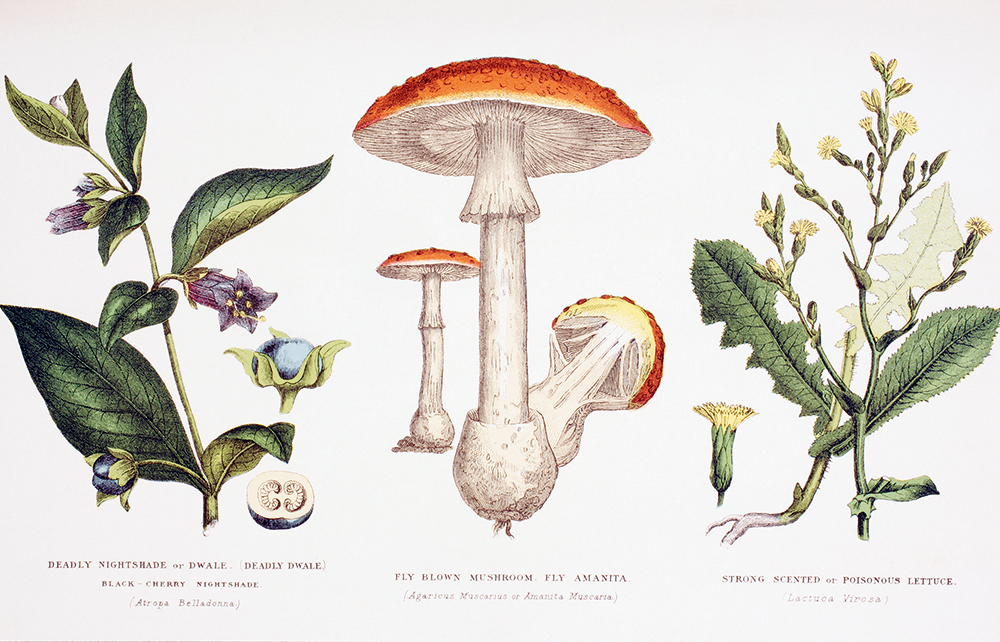

The author of this book, a professor of biology at Berkeley, takes us on a global trip through plants and their chemicals. It’s a kaleidoscope of facts and historical vignettes, both of how plant chemicals work, and how humans learned to harness some of them. He explains how scientists identified and were able to produce widely used drugs such as aspirin and codeine from their plant sources, and how cocaine made its way from leaves chewed in the Andean hills to a local anaesthetic used in eye surgery and every partygoer’s nostrils in the 1970s.

But his focus is not just on the compounds we employ medicinally or recreationally. I had never really thought about the ink used in the 18th century. It was iron gall, derived from the tannins in oak galls made by tiny wasps. Small insect product was used to sign the Declaration of Independence – and the nature of tannins is what makes such old documents hard to preserve.

Forest-bathers actually gain from from the Valium-like calming effects of volatiles emitted by trees

We learn that montane voles’ breeding is affected by chemicals secreted in grass that basically act as a reproductive hormone, telling them it’s spring and turning on their fertility.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in