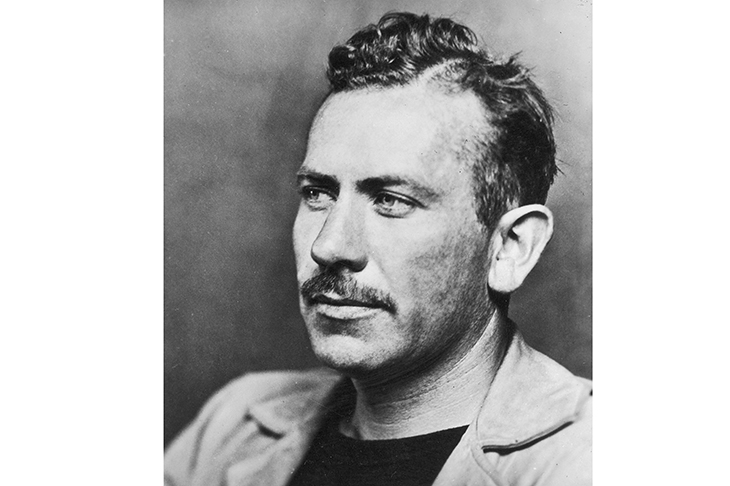

John Steinbeck didn’t believe in God — but he didn’t believe much in humanity either. When push came to shove, he saw people as cruel, selfish, dishonest, slovenly and, at their very best, outmatched by environmental forces. Like his friend, the biologist Ed Rickett, Steinbeck considered human beings to be no better and no worse than any community of organisms: they might aspire to do great things, but they always ultimately failed.

In The Grapes of Wrath, the hard-working Joad family travel west, seeking a good life, and get taken apart by poor wages, malignant farm cooperatives and company stores. In Cannery Row, Mack and his boys want to repay their friend Doc for all his generosity, and end up burning down his lab after a drunken party. And while the paisanos of Tortilla Flat see themselves as noble knight errants right out of Malory’s Morte d’Arthur (Steinbeck’s favourite book as a child), whenever it comes to a choice between doing good deeds and feeding their bellies — well, spoiler alert, their bellies always win.

Steinbeck never wrote about heroes and villains; he was more interested in the ways individuals were shaped by their environments and their communities. In order to create characters, he wrote in Cannery Row (1945):

You must let them ooze and crawl of their own will onto a knife and then lift them gently into your bottle of sea water. And perhaps that might be the way to write this book —to open a page and let the stories crawl in by themselves.

For Steinbeck (as for Zola), fiction was a laboratory experiment. He reserved his greatest love for the natural world — especially the mountains, valleys and surging shorelines of his beloved California. In one of his weirdest novels, To a God Unknown, his ranch-building protagonist, Joseph Wayne, makes love to the earth in one scene and, in another, speaks with his dead father’s spirit through an old tree.

Comments

Join the debate for just £1 a month

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for £3.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just £1 a monthAlready a subscriber? Log in